Irish Searches: Izvestia publishes a fragment of Paul Lynch's book

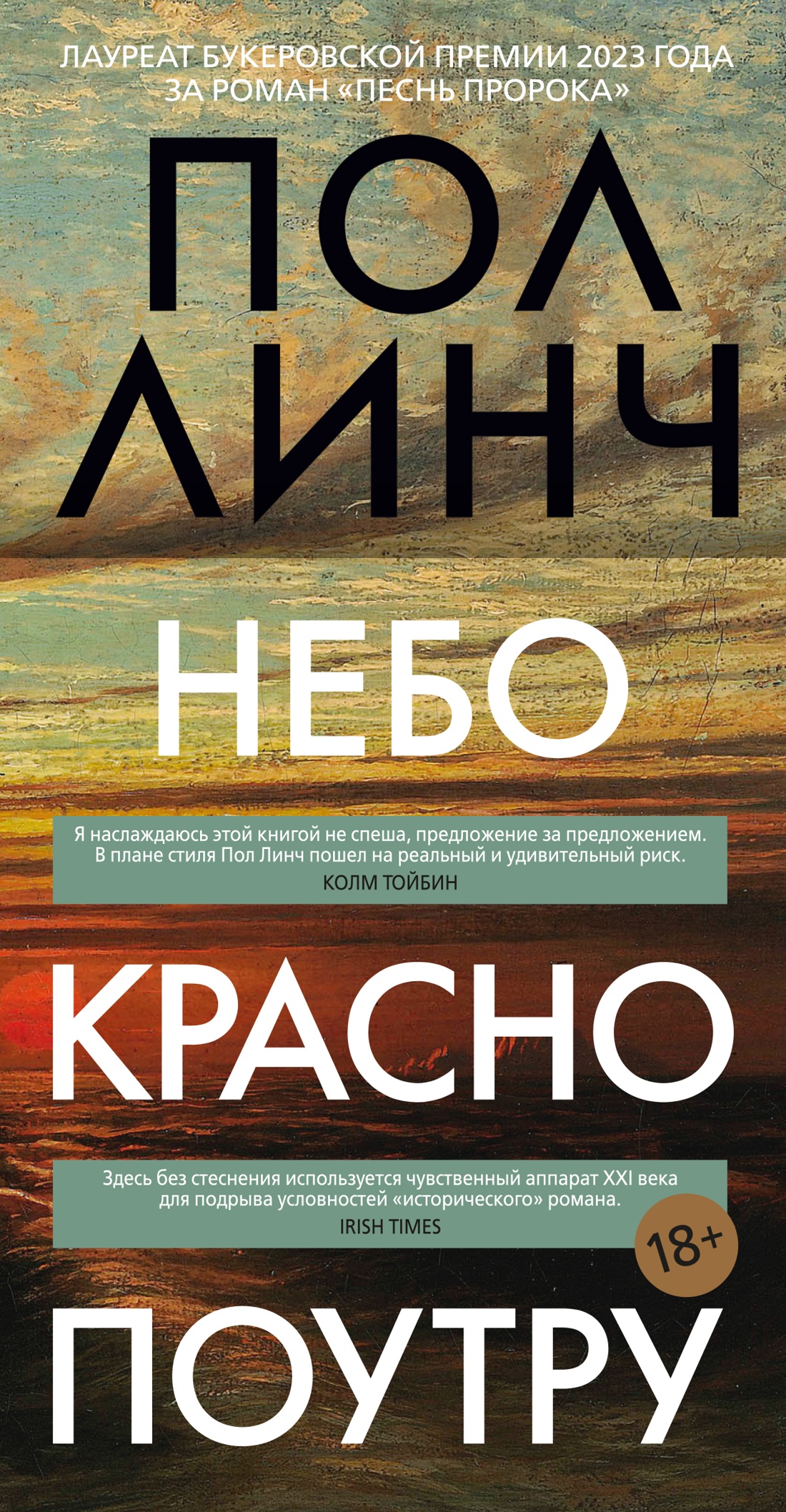

The name of the Irish writer Paul Lynch has been reverberating in the West for more than a decade, but the general public in Russia learned about him thanks to the Booker Prize, which the novelist received in 2023 for The Song of the Prophet (Izvestia wrote about this work). Grace and Beyond the Sea are also available to Russian readers, but Lynch's debut book, which brought him recognition in his homeland, The Sky is Red in the Morning (2013), has only now been translated into Russian. On March 31, it is published in the publishing house "Inostranki". The hero of this dark quasi-western, written in dense, charismatic language, commits a murder in Ireland and flees, pursued, across half the world. Izvestia publishes an exclusive fragment.

Paul Lynch, "The Sky is red in the morning" (fragment)

Translated by Maxim Nemtsov

No one could say how long the riderless horse stood in the yard unnoticed. She ghosted into the stable yard, her eyes wild, and her bronze pelt bristles with thorns. The whiteness of her bangs is stained with mud, and her muzzle is smeared with blood. Foller was called, and he strode out of the house, black boots shining, and cold eyes in their motionless position of a smile. Workers huddled around the horse, muttering, and some of them looked anxiously at the man in the hope that he would provide them with some kind of reassurance or explanation regarding the nature of what lay before them, but the man showed no emotion at the sight of the riderless horse. He took the beast's head in his long palms and looked at the scarlet tapestry, examined the animal's flesh to see if there were any mutilations, and when he couldn't find anything, he touched the wet substance with his finger and spoke under his breath in words that were clear to the audience as day: it wasn't horse blood.

Jim was standing, stirring hay in the barn, when a worker stepped into the twilight.

—Hamilton's horse has returned, but there is no rider, and there is blood on it," he said.

Jim stuck the pitchfork into the hay and went outside. He pushed his way between the people, clenching his teeth tighter and tighter. He put his hand on the beast's side, and pulled thorns out of the skin, and spoke softly to the mare. And when he turned the horse around, he saw the jacket rolled up under the traces, and bent down, and immediately recognized whose jacket it was, and it seemed to strike him with an enormous and instantaneous weight. They were talking about a search party, and then Foller appeared at his shoulder. He ordered without raising his voice, after which he reached over Jim's head, and took the jacket, and unfolded it. He spread it out in front of him in the air, and then strode towards the house with the find in his hand. The men put down their guns and went to the outbuildings to get their jackets, and Jim took the horse to the stable. He guided her to the stall, and rubbed her nose, and took hay, and put it to her mouth, and stood and walked back and forth, and when he went outside, there was movement of people near the house. He went in the other direction, found that his legs were running, and he was overwhelmed by the feeling that the natural order of things had slipped in a way that could not be fixed.

People fanned out along the path Hamilton preferred. Foller walked slowly in front, head bowed, looking closely at the signs. The turf was soft and gave way underfoot. About a mile from the house, people reached the wall and watched as Foller bent over the wet earth, testing it with his fingers.

Then he straightened up and spoke softly to a man named Maken, who turned around, his face worn and polished like boot leather, and the empty eye socket sealed with a fold of flesh, and beckoned to another of the people in turn. The three squatted down, and Foller pointed to the ground and the bustle of footprints. After that, he got up and slowly walked in the other direction, and his eyes traced the blood against the wall, and the blood spread across the grass, now blurred by the rain. He bent down to the stones and touched them with his finger. Maken squatted down too.

The others stopped and watched. Foller pointed to the traces of dragging on the grass, and then straightened up, and looked at the ground, and walked until he reached the gate and stopped in a clearing near the trees, where he bent down and touched the ground, and his hand was stained with blood, and then he turned in that direction, and his two went with him.

Evening was already falling when people stepped onto the swamp. The rain had stopped, and a pillar of sun had been erected on the heather, as if asserting its right to this plain. Two of them followed Foller, who kept bending down to the moss, checking the soil for footprints, seeing things that the other two did not see, but they nodded to each other, recognizing the abilities of the third, supernatural, they said, and kept quiet behind him.

Ahead, they could hear a dog barking, and then the shape of a beagle appeared. Maken called out to her, recognizing her, but not a word from Foller, but his gaze did not leave the dark beast, and he went to him, while the dog barked enthusiastically, as if it could speak directly to the gigantic man.

Later, when the clouds rolled over and the darkening pallor of the evening began to fall, they pulled the body out of the quagmire. The horse was straining in its harness, and the sucked-in barrel did not want to give away its secret, clinging to the corpse, which slowly poked out in its dripping blackness, a rope was thrown over a single boot.

The dog was barking and circling between the people standing by the ash tree. The air was buzzing with the tension of unexpressed stares, the realization that they must be dealing with a murder, not an accident, and now hats off out of respect for Hamilton, their fallen employer, every man except Foller, who left his hat on his head and sat down at a distance from the men. squatting with a pipe in one hand and a tin can in the other. He took a pinch of tobacco and twisted it between his index finger and thumb to knead it, then flattened it and patiently sucked it into the tube to make it come alive.

And only when the deceased was lying stiffly on the ground, I went up to him and brought my hand to his face, carefully wiping the slush from his features, silt stuck to his eyelashes, and his teeth were gnawed, and his mouth was filled with black oozing slime, and rubbed his thumb over the dead man's lips.

There was silence in Hamilton's house. The oil lamps were being lit, and the whispers were no more than a breath away as Foller approached while walking through the hall to the east wing of the house. The gallery of deer heads looked on impassively when the dresser entered the living room, the shadows from the antlers dimly dappled the ceiling.

Hamilton was standing in front of the fire, and he turned and looked at Foller. He was white and naked, wearing only leather flip-flops and a robe that hung loose, and in his arms he was nursing a stuffed fox. Foller reached out to light an oil lamp and watched as the old man whispered in the animal's ear.

"That was one of the Coyles, sir,— Foller said. Hamilton stopped whispering and looked up at the dresser. "What is it?" he asked. The old man's voice is a halting whisper.

"Your son, sir."

—Oh, that. I understand. Have you talked to Desmond about this?

"It's Desmond who's dead.

The old man looked at him without blinking with watery fishy eyes.

— I understand. What a pity.

He lifted the fox up to his face.

"I don't think we're going to miss him, are we, Liska?" We didn't like Desmond anymore, did we?

Foller went to the sideboard, picked up a glass, and poured himself a scotch. The leather chair creaked as Hamilton sat down in it, the gray flesh of the belly loosely fell out onto his groin, and Foller watched as he stroked the animal's head.

"I didn't involve the constabulary," Foller said. "I don't intend to. And my word to you, I'll bring this scoundrel to you.

Hamilton inclined his ear to the fox, and Foller turned to leave, but the old man raised his head again, and Foller could see that the dim light in his eyes had come to life.

— Liska says he wants a cup of hot milk.

She reached out to him, put the baby in his lap infant skin is warm, and diapered baby with the eyes-and saucers, and looks up at him and his finger all the clasped handle — the tiniest of a wonderful living creature of all, what he saw when he softly sang the baby in my ear the melody strange in his mouth, which previously did not sing, but she appeared to him easily, like he knew her my whole life, and stood before the fire he with baby on hands, and saw the horse and rubbed her face with his hand, and she came up and also hugged her and said the words that he failed to make out, but then her ears started bleeding, the soft sound of rain on the floor, and he told her to be careful with blood, but she had already flowed, falling to the clay, and her face is wild, eyes Nemo scream, and he screamed and held his hand to one ear of the horse, but the flow has to stop could not, and she began to shout at him, and now he could hear her, where is the little girl, Call, where you, the little man left, and he didn't know where I left the baby, and stood there, not knowing the horror chained him to a place he could feel the strength leaving his legs, and the horse looked at him sadly, and he is all cold from the cold.

His awakening breath is suffocated by the mute darkness. A rush of forest air filled his nostrils, and he fixed his eyes on the starless night. His body was soaked and tingling, but he was lying in a hollow, and then he sat up, his arms and legs would not bend, his shoulders were like a stake after the bare earth from the cold. His shoes got wet next to him, and he tucked his feet under his knees and rubbed his body for warmth, cursing the loss of his jacket.

His cheekbone hurt, and he remembered how his brother had attacked him outside the house that day. The man is furious. In front of Sarah, and Jim knocked him to the ground with his fist.

"You'll be hanged,— he said.

"I don't know. No one knows anything, that's why they don't.

"You're a complete fool. They've seen your jacket. You need to go.

"I'm not going anywhere."

— If you don't go, you'll disappear before dawn. Get out now and hide somewhere. Go to Balamut at least for this night. I'll make sure that Sarah is looked after.

The night was quiet, and he figured it was well past midnight, and in that silence he listened to his stomach rumble. He felt for his shoes, put them on, and set off through the woods. I walked further along the path away from Carnarvan, hugging myself with my arms, but the ground was dark under my feet, and everything that was destined to be was wrapped in its own darkness.

He heard movement in the forest. Twigs crackled, and he froze in place. There was a rustle nearby, but he couldn't place it, and his breathing stopped. He slowly squatted down and crouched down, holding his breath in his mouth. I listened to the wind whispering in the tips of the trees, and I heard the dull beating of my heart in my ears. He stretched out his hand to the ground, patted the forest floor in a semicircle, there wasn't a suitable stick, but there was nothing to catch on, and the rustle got closer, and he closed his eyes, squeezed them shut, and when he opened them again and listened, there was nothing in the night. He waited and sat quietly. In his mind, he saw his wife, and his baby, and the baby that was just waiting to come true, and he thought about all the troubles that would befall them, and he got up. He looked at the black-edged ridge of Banowen and the hills, darkly nameless beyond it, and turned back to the house, back the way he had come.

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»