Naked among the clothed: Franz Kafka found himself between life and writing

This is not just another biography of one of the greatest writers of the twentieth century, but an attempt to comprehend his life and work using the methods of philosophy. Critic Lidia Maslova presents the book of the week, especially for Izvestia.

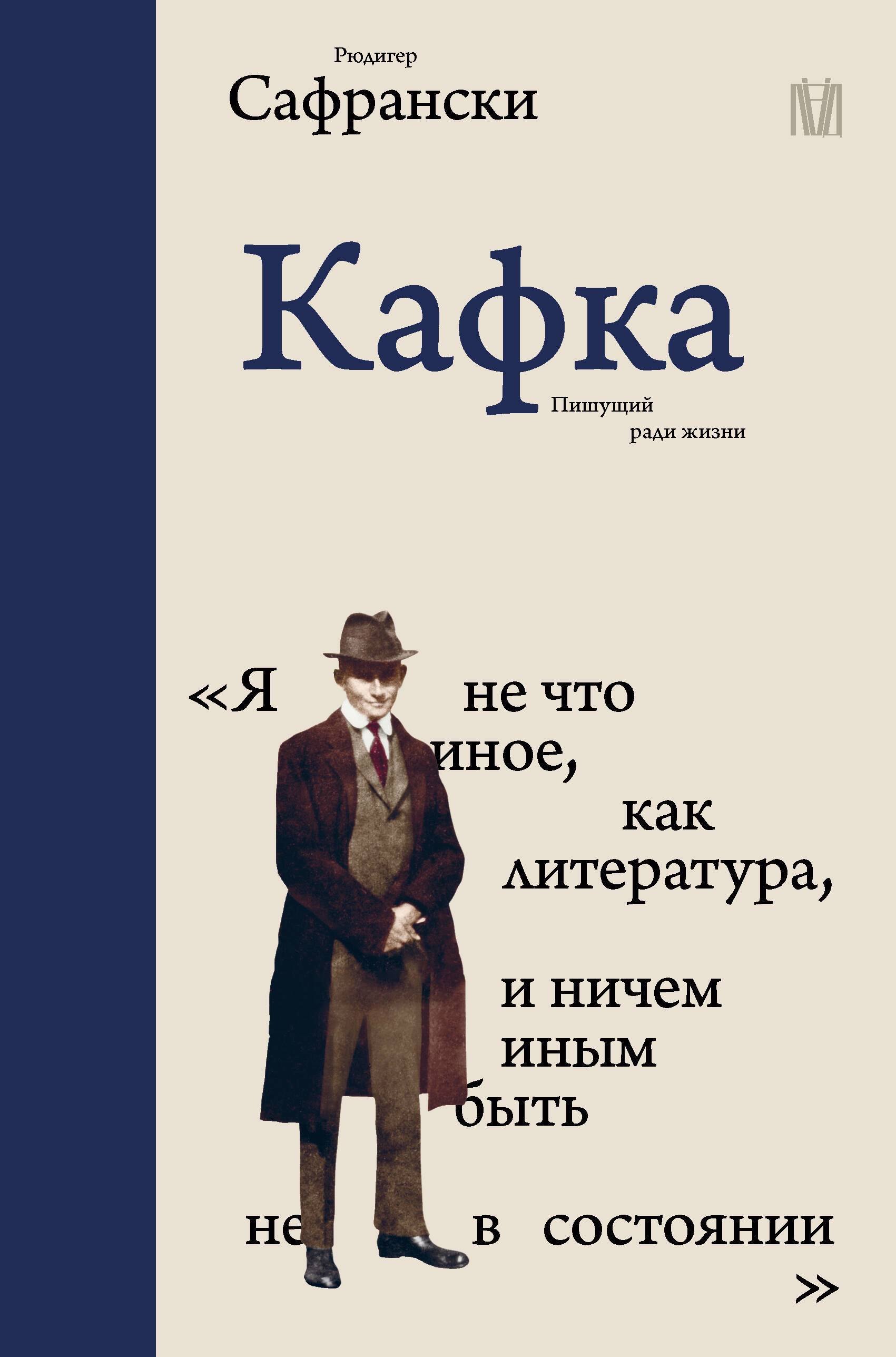

Rudiger Safranski

"Kafka. Writing for the sake of life"

Moscow : AST Publishing House, 2025. translated from German by S. O. Mukhamedzhanov. 320 p.

Due to the ambiguity of the German preposition "um", the original title of the Heideggerian philosopher Rüdiger Safranski's book about Franz Kafka contains a touch of wordplay: Um sein Leben schreiben is, firstly, just "writing about your life", but at the same time "writing to survive". In the pathetic Russian translation of "Writing for Life," the categorical imperative comes to the fore (you can't not write, it's impossible), and besides, the personal pronoun "sein" (your own) naturally disappears, as if hinting that Kafka wrote exclusively about himself and, in the process of writing, solved primarily his own psychological problems.. On the one hand, it was true, but when the individualistic pronoun disappears, the global, universal meaning of Kafka's scrupulous introspection is emphasized.

The idea that Kafka, who has a reputation as a closed, neurotic crank and an incomprehensible autistic, actually still supports a lot of people, helping them cope with life on this not always comfortable earth, does not contradict Safransky's view at all — in fact, that's exactly what he's aiming for. At the end of the book, the philosopher points out the comforting and harmonizing component of the Kafkaesque worldview, quoting Kafka's last story, "The Singer Josephine, or the Mouse People," which describes the effect the squeaking of the singer Josephine has on mice huddling together.: "The whole mass of listeners <...> withdraws into themselves. In these meager intervals of rest between battles, the people dream; everyone relaxes tired muscles, as if he, a hard worker, for once was given to stretch out and luxuriate in a spacious and warm bed."

According to Safransky, Josephine is Kafka himself, who invariably identified with his characters, and on the eve of his death, with his characteristic self—deprecation, described his work as a "confidential whisper with hoarseness" or worse, a mouse squeak, which is not the fact that it is art, but most importantly, it still gives the poor little mouse "the opportunity to hear oneself" and thus "liberates from the shackles of everyday life."

In fact, Kafka's entire short life was devoted to attempts to break, loosen, and somehow weaken these shackles. Safransky begins his description with a programmatic statement from his hero: "I have no inclination towards literature, I just consist of literature, I am nothing but literature, and I cannot be anything else." able to." Just as you can write "about life" and/or "for the sake of life," Safransky's book can be read on one of two planes — the theoretical-philosophical or the everyday-emotional, and ideally, of course, it is better to combine them, especially since there are no impenetrable partitions between them, but there are a direct connection, obvious even to the reader who is not very well versed in philosophical terminology.

Safransky periodically tries to rush into the terminological wilds, but quickly pulls himself together, illustrating Heideggerian thought bells and whistles with concrete examples from Kafka's writings, letters and diaries, and the fog clears. In addition, in the preface, translator Stanislav Mukhamedzhanov cautiously introduces exactly what motives the author of the study draws attention to in relation to Kafka. Thus, the key concept of Heidegger's main book "Being and Time" — an existential sketch — can be traced in the story "Sentence", where "the hero and his friend, lost in distant Russia, are two mutually exclusive existential sketches of Kafka himself."

Although Safransky describes these sketches as "mutually exclusive," it seems that a variety of sketches, life arrangements, opportunities to adapt to society or, conversely, to better hide and isolate themselves from it, got along well in Kafka's bizarre brain. On the one hand, he sincerely felt like a stranger in the world around him, a man who seemed to be "slow to be born" all his life and was experiencing many social fears (before his father, sexuality, social communication, metaphysical homelessness, the negativity of the era in which he had to live).

But at the same time, Kafka honestly tried to become a "normal" member of society and in many ways succeeded in forcibly "domesticating" himself, diligently performing the necessary "philistine" rituals and manipulations, for example, he went to furniture stores with his first bride, Felicia Bauer. Although without any pleasure, he made an excellent career in the Workers' Accident Insurance Society, where he was a universal favorite and earned respect for his professionalism ("Colleagues were surprised by the stylistic perfection of the documents he compiled"). He complained of loneliness, but "maintained numerous and strong friendships": who has not heard of the devoted Max Brod, who did not fulfill Kafka's will and preserved his unpublished legacy instead of destroying it?

And finally, despite all the sexual complexes, Kafka, with his interesting appearance, enjoyed success with women, who, judging by Safransky's psychoanalytic reasoning, had a lot of nerves (this, however, was a two-way process) before he began to come across those who understood and accepted him as he was. One of the smartest was the penultimate lover, Milena Yesenskaya, who created a concise but comprehensive portrait of Kafka in a letter to Max Brod: "He is completely incapable of lying, just like he is incapable of getting drunk. He has absolutely nowhere to go, he has nowhere to hide. That's why he suffers from everything we're protected from. He's like naked among the clothed."

The cross—cutting idea of "Writing for Life" — Kafka's exhausting tossing between life and writing - culminates in the chapter where the novel "The Process" is analyzed. Safransky mentions the famous film adaptation by Orson Welles, who followed the simplest path of interpretation and shot an anti-totalitarian dystopia about how the bureaucratic apparatus suppresses personality, but Kafka's everything is much more interesting and subtle. Safransky suggests that the unfolding trial in the novel should not be viewed solely as an "oppressive force.": "Suddenly it turns out that he is somehow connected with enlightenment and almost salvation. <...> The inappropriate life that Joseph K. led up to this point is a life conformable to society, and what begins with a willingness to feel guilty is a process as an experience of existential awakening. <...> The process forces Josef K. to experience an inner judgment day, when his own life is being tested for strength."

Speaking about the individual, inner court, which "forces a person to face himself, pulls him out of his habitual, well-ordered life," Safransky announces two charges of this "inner court" of his hero: because of writing, he misses life, and because of life, he misses writing. "Kafka is moving in this endless cycle of guilt," Safransky states, and this was probably Kafka's prevailing inner sense of self: "At first glance, the result he sums up seems bleak. He failed at nothing: a family that annoys him, but which he cannot leave. Marriage, although it came to engagement twice. Literature and writing are his true passions, but he brings only a few of the things he started to the end. A job where he is appreciated, but which he does not like. Therefore, Kafka's diagnosis sounds like this: collapse in all respects."

But now, a century later, the outside observer-reader does not see everything in such a gloomy light — for him Kafka is rather an inspiring example of virtuoso existential acrobatics, which allows, even at the cost of incredible nervous tension, shortening the period of biological existence, still to sit on two chairs with his own unique persona.

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»