Picturesque in everything: before whom Marlene Dietrich fell on her knees

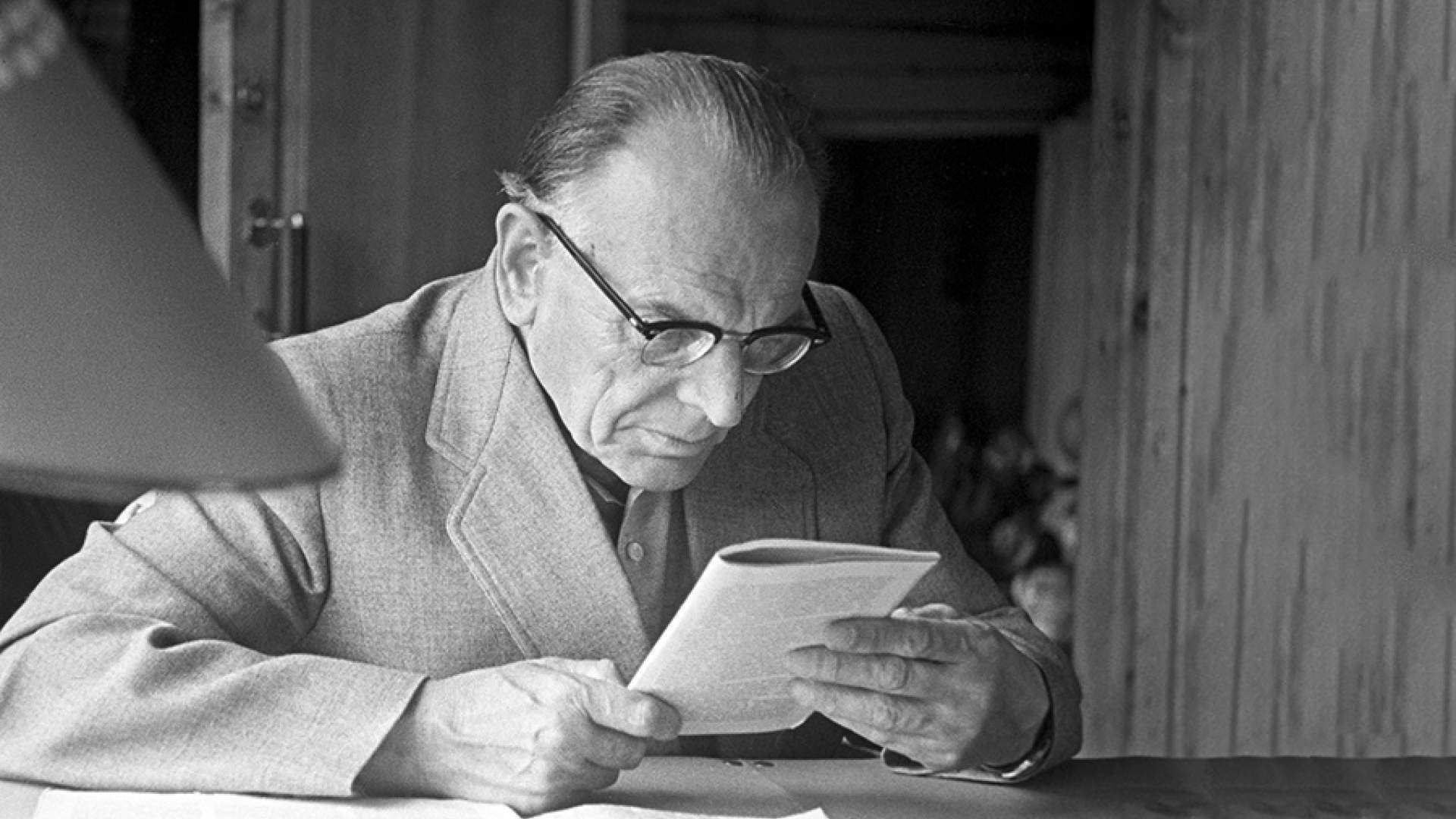

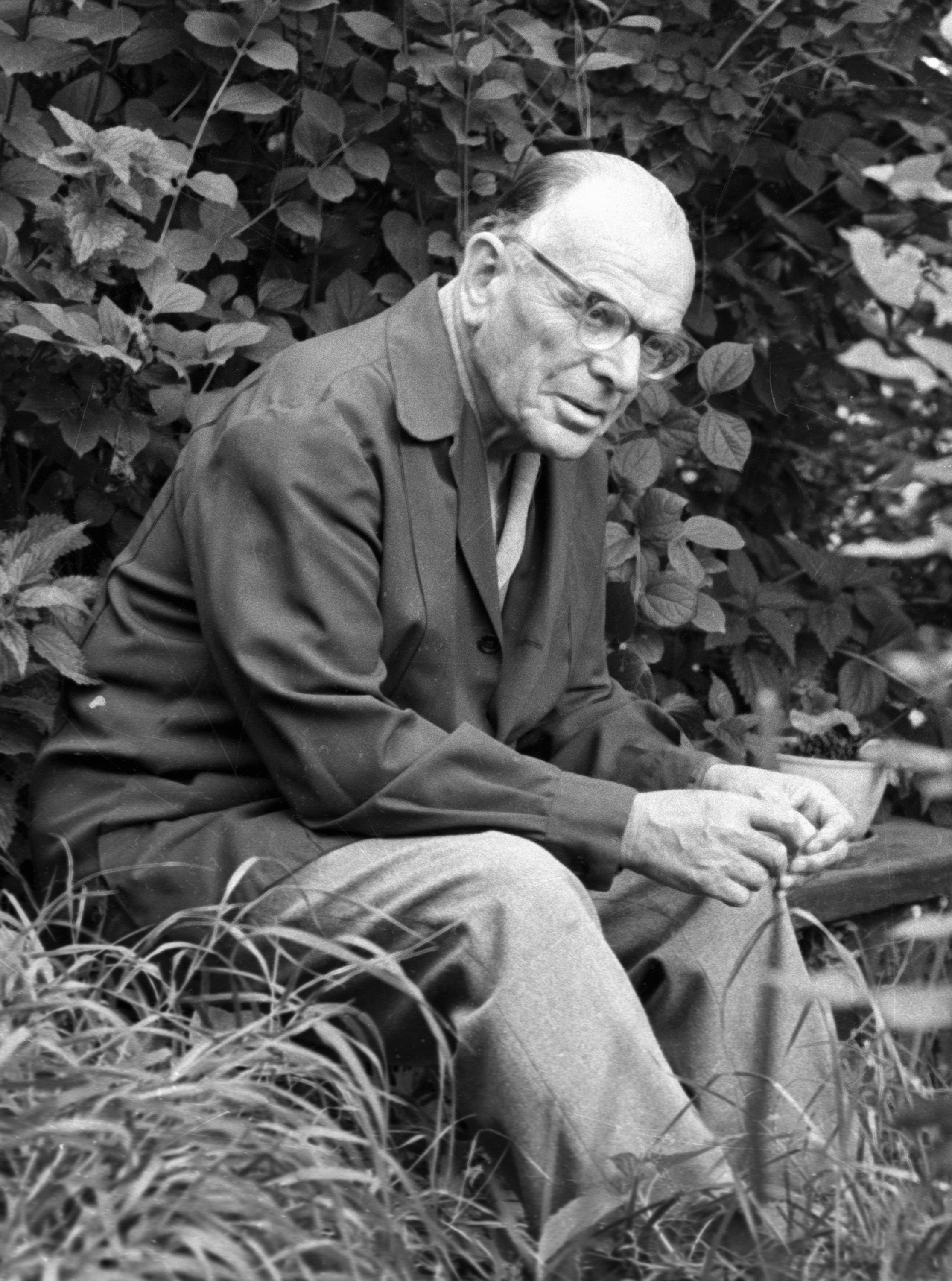

During her tour of the USSR in 1964, the great actress Marlene Dietrich expressed her desire to meet only one person. And no, it was not the all-powerful Nikita Khrushchev or the world-famous Yuri Gagarin. Marlene wanted to see in person the author of the story "Telegram", a modest elderly man with horn-rimmed glasses, writer Konstantin Paustovsky, who had once amazed her. He came to her concert in TsDL - and the legendary diva of the screen knelt before him right on the stage. Learn more about Paustovsky's life can be found in his new biography. Critic Lidia Maslova presents the book of the week especially for Izvestia.

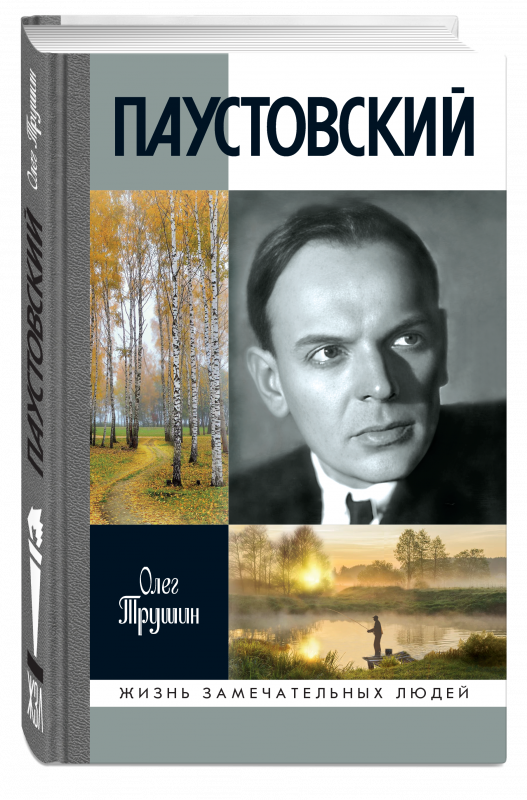

Oleg Trushin

"Paustovsky: Dissolving Time"

M.: Molodaya Gvardiya, 2024. - 395 с.

Lyrical subtitle of the biography of Konstantin Paustovsky - "Dissolving Time" - its author Oleg Trushin stealthily explains, polemizing with one of the through characters of the book, proletarian critic Galina Kolesnikova. Actually, the title of her article about Paustovsky - "In Search of the Unusual" - published in № 10 of the magazine "October" for 1934, can serve as a concise key to everything that Paustovsky valued in literature, foreign and his own. The strict and fastidious Kolesnikova helps Trushin to draw the most important touches to the portrait of Paustovsky, marked by a desire to belles-lettresize the dull prose of life, various mystifications (including a free treatment of his own biography), and most importantly - a sincere romanticism that captivated the general reader. "Prose writer Paustovsky beautiful in everything," - admires the biographer, already in the epilogue, recalling the phrase from Paustovsky's essay "Uncle Gilyai", which, according to Trushin, fits and his hero: "He was picturesque in everything - in his biography, appearance, manner of speaking, childishness, in his versatile and exuberant talent."

How perceived Paustovsky most grateful reader - the little - Trushin shows, quoting an article from the magazine "Book of Youth" № 8-9 1932, timed to the release of the story "Kara-Bugaz" and compiled from the reviews of schoolchildren: "Pioneer Kharin, a student of the fourth group, like others, agree with Rabinovich, but adds:" No, guys, it is much more interesting than Jules Verne. Jules Verne writes in a difficult language, he has a lot of obscure words, but here the language is very clear and the truth about revolutionaries is described". Professional writers also appreciated "Kara-Bugaz", in particular Nobel laureate Romain Rolland, who noticed the birth of a new genre in Soviet literature - "literary works showing individual geographical points".

"Paustovsky, unwittingly becoming one of the discoverers of the new genre, defining its name for himself as "history with geography", all subsequent years will work in it," writes Trushin, who believes that "the symbiosis of socialist realism and romanticism, history and scientific subtext, "flavored" with adventure intensity, <...> made "Kara-Bugaz" a special phenomenon of the literature of its time" and allowed Paustovsky to step out of the shadow of Alexander Grin. Dividing Paustovsky's biography into three parts, Trushin believes that "the first of them passed under the sign of "Clouds of Glittering", the last one is covered with the glory of the "Tale of Life", well, and the second one is blessed with "Kara-Bugaz" - a story that set the right vector of the genre line of all subsequent works of the author, regardless of their form.

However, this "necessary vector of genre line" was not immediately clear and obvious to everyone, including the same Kolesnikova, who believed that Paustovsky's "vagueness of genre <...> is the result of the search for the unusual", and the main problem is that landscapes and spectacular phenomena of nature succeed better than people: "...he must learn to feel and give people in all their human complexity. To be able to show people as convincingly as the author does when it comes to phenomena and events". Trushin strongly disagrees with the critic who stubbornly does not want to understand what Paustovsky wanted to say in "Kara-Bugaz": "The connection of the present with the future, allowing not only to dissolve time in space, but also to gain an understanding of its new property - the reincarnation of the present into the future".

This beautiful but vague phrase well reflects the specificity of Trushin's own manner. It consists in a peculiar, sometimes overcomplicated word usage, often forcing the author to gratuitously punctuate ordinary words that are absolutely appropriate and understandable in a given context, but, apparently, Trushin himself seems insufficiently precise. For example, telling about how the idea of writing originated in young Konstantin under the influence of Alexei Gilyarov, a philosophy teacher at Kiev University, Trushin metaphorically remarks: "Writing for Kostya Paustovsky was like a 'spoonful of antidote' from everything that surrounded him in those years, from what his soul was thrashing." One "antidote" without any quotation marks, as well as without "similarity" and "spoon", would have been quite enough here, and "from what" in this situation would have looked better separately. But, unfortunately, proofreading and editing in general has been rather negligent with Trushin's book and missed many small but annoying and ridiculous "fleas": "realizing" instead of "prevaricating", "mokhovik" instead of "machovik", magazine "Plow and Molod".

Not infrequent in "Paustovsky" are roughnesses concerning the consistency of participles and prepositions control ("atmosphere of discontent to the authorities", "spectacularly to the perception"), as well as tautologies weighing down the reading, when the author's correct thought would only become more evident if the editor cut off a few extra words, for example, in the passage where the fundamental difference between Paustovsky's works and the samples of condensed socialist realism is formulated: "A literature not conjugated with a social order, but one in which the image of man is at the head of the whole theme of the narrative."

As for Trushin's careful, "doubting" quotation marks, they are, on the contrary, lacking in some places, because the meaning of ornate constructions and epithets is not quite clear, for example, the word "jealous" in the following sentence: "But let us return to Paustovsky's grammar school years - a bright and very jealous in time period of our hero's life, in which everything was intertwined: childhood and adulthood, the loss of his family and the acquisition of early independence. When you try to read the next sentence (maybe there will be an explanation of the "jealous period"?), you plunge into a stormy waterfall of words, where "time" is again too obsessively repeated on every line: "...".it was a happy, and maybe even the happiest time in his life, not yet burned by the tragedies of wars, the chaos of revolutions, a time when one ideal was replaced by another and one after another waves of a new era, swallowing up millions of lives of his compatriots of his time".

The obvious editorial and proofreading omissions, however, do not cancel the value and fascination of Trushin's book, and even more so the human charm of the figure under study. It shines through even more vividly when the floor is given to those who had not just a long list of artistic complaints against Paustovsky, but who generally considered him a worthless writer or "a mumbler with beautifully soulful, sluggish, false-romantic criticism, not at all dangerous to the authorities" (this is the opinion of Nadezhda Mandelstam, whom Paustovsky helped to get a Moscow apartment in 1965). Such an authoritative detractor as Alexander Tvardovsky, editor-in-chief of the New World, felt, in Trushin's opinion, almost personal dislike for Paustovsky. But the more convincing and objective is the entry in Tvardovsky's diary as a kind of eulogy immediately after Paustovsky's death: "He was undoubtedly a bad writer, but at least he was a man of the old literary faith, reverent before it - literature, which is not only inaccessible to people accustomed to supervise it, but also reprehensible, as a remnant of paganism after the introduction of Orthodoxy.

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»