"I washed Eisenstein's tombstone"

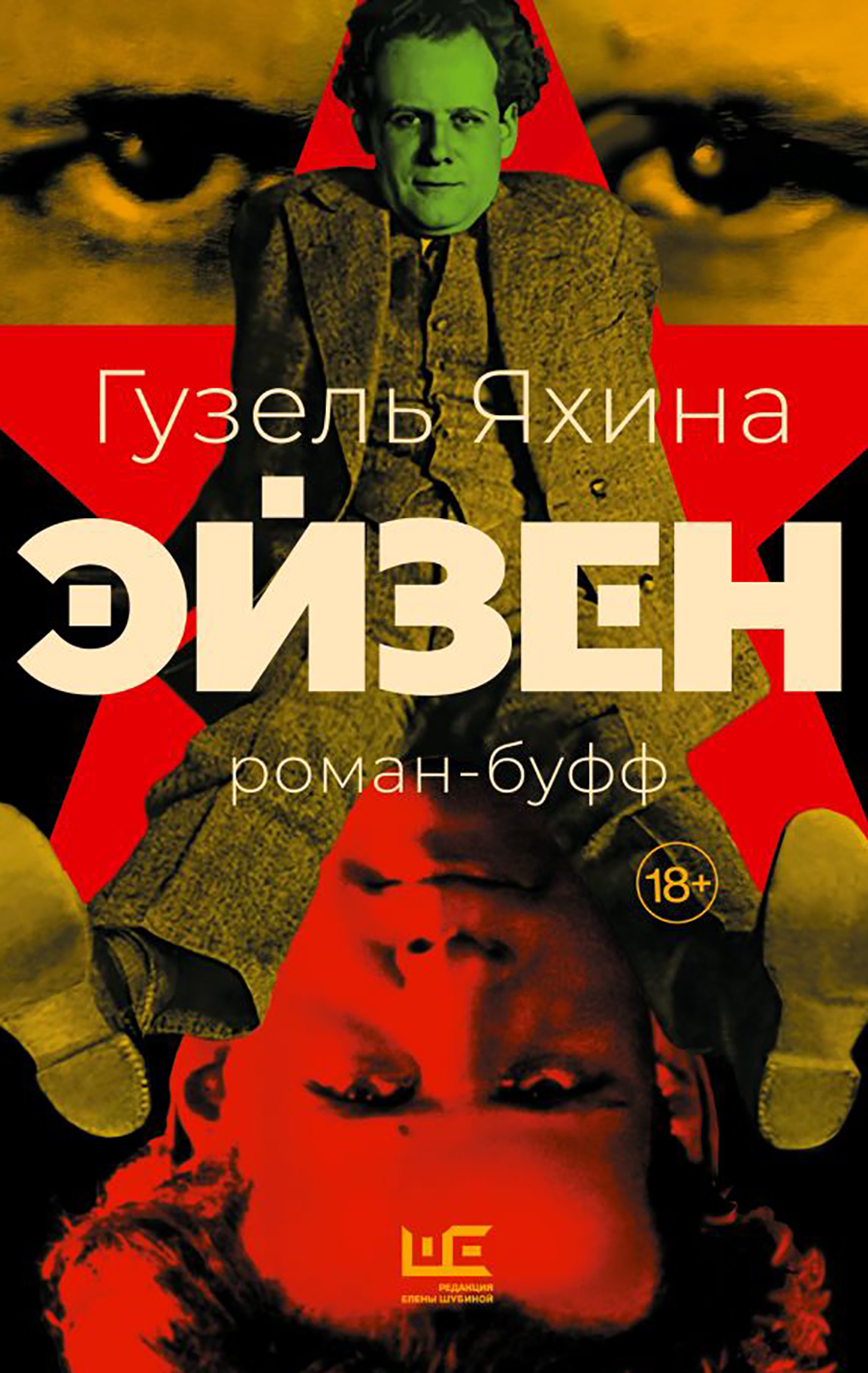

Three years of research, doubt, trial and error — that's how, according to Guzel Yakhina, the author of the hit "Zuleikha Opens her Eyes," the novel "Eisen" was written. Eisenstein is an artist, Eisenstein is a man, Eisenstein is a citizen - these are all separate worlds that needed to be put into a single narrative and make it fascinating at the same time. The novel is already on sale, and, as Izvestia learned, in the largest federal bookstore chain, Chitai Gorod, after the release of Eisen, sales of the author's works doubled, pre-orders numbered in the hundreds, and over 230 thousand copies of her books were sold online. Izvestia talked with the writer about what was the most difficult thing in creating an artistic biography of the main director in the history of cinema and what were the main tasks of this work.

"Eisenstein walked the fine line

— You've been working on a book about Eisenstein for three years. Have your ideas about this figure changed in any way during this time? Is it possible to say that your attitude towards him has undergone any changes in the course of your work?

— Sergey Mikhailovich Eisenstein evokes the most contradictory feelings in many researchers, including me: from adoration and delight to indignation and extreme surprise, and all this at the same time. I can't help but admire "Ivan the Terrible": both the masterpiece film itself, and the conditions in which it was shot (the evacuation to Alma Ata), and when it was shot (a powerful anti-totalitarian statement was made in the mid-1940s). I can't help but respect the incessant scientific search for Eisenstein, the pioneer of cinematography and the founder of Soviet art.

But I can't forget about his extremely difficult relationship with his mother, as well as other (very many) women in his life. And most importantly, that Eisenstein spent his whole life walking a fine line between art and propaganda, falling one way or the other — not at all embarrassed by this and willingly paying a political price for the opportunity to make a movie.

At the beginning of the work on the novel, a very important question arose, which remained unanswered for a long time: how to make you sympathize and sympathize with the hero, whose actions evoke, rather, the opposite feelings? Empathy is the main thing in narrative art, without it, the interest and involvement of the reader or viewer is impossible. I didn't want to embellish the hero, nor to denigrate him; the task was to write an honest novel that would present Eisenstein, the man in all his complexity and inconsistency. I was very afraid of falling into chastisement —I had neither the right nor the desire to do so. Colleagues on the shop floor even advised to give up, not to take on such an ambiguous hero.

Then I went to the Novodevichy cemetery, found Eisenstein's grave, washed the tombstone, and laid a rose. And she mentally asked Sergei Mikhailovich himself: What should I do? Should I write a novel or not? The answer was unequivocal: of course, write! Sergei Mikhailovich himself would have been in favor of any statement about himself, even if it wasn't the most complimentary — I realized that there, at Novodevichy, and decided there.

And I've been dealing with the issue of reader interest for all three years of my work — I've tried to write a novel vividly, variously, constantly switching the genre register from comic to drama, from satire and sarcasm to lyrics, so that this change intrigues the reader and at the same time reflects the essence of the hero: Eisenstein lived for show, gushing with ideas, projects and passions — a kind of fireworks man. I hope that the attentive reader will see the tragedy behind this brightness, genre polychrome and the sign "roman-buff" — Eisenstein's great talent became his misfortune. Throughout his life, Eisen the artist grew and enlarged, eventually acquiring a cosmic scale, which cannot be said about Eisen the man - the conflict between Artist and Man eventually destroyed Eisenstein.

— What was the main surprise, the main discovery for you when you immersed yourself in this topic?

— The main discovery about Eisenstein was his complete defenselessness in the face of researchers. Throughout his life, Eisen exploited everything at his disposal to create his films: he reshaped history, constantly drew from the work of other artists, and instrumentalized biblical and mythological plots. And over the past 50 years, he has written-done-filmed-said so much, was so vivid in all these manifestations and wore such a huge number of masks that now he himself can be turned on almost any side — used for any, including political, purposes. If you want, you can mold him into a desperate propagandist, or you can mold him into a great artist in a cage of totalitarianism, a holy martyr on the altar of art. If you want, it's Faust, who is ready to sell his soul for solving the main mystery of art, and if you want, it's Antifaust, who sacrifices himself for the sake of his creations. We wanted to avoid such exploitation. I wanted to understand Eisenstein — not to justify him, but to understand him in all his complexity.

— In recent years, at least two big films by Peter Greenway and Alexei Fedorchenko have been released about Eisenstein. Alexey German is preparing to make his own movie about him. Why did Eisenstein suddenly become so important today?

— The film "Eisenstein in Guanajuato" was released ten years ago and tells not about the fate or creativity of the hero, but about some aspects of his personal life — this is what worried director Peter Greenway the most. As far as I know, he was in Russia for a very short time. I'm not sure if this painting can be called a hero study.

The same applies to Alexey Fedorchenko's film "The Last Sweet Bulgaria".: Eisenstein is an episodic character there and appears only a couple of times. So the situation is rather the opposite: great artistic statements have not yet been made about the most famous Soviet director.

Perhaps this is due to the complexity of the character — it is difficult to approach him. Eisenstein himself also "gets in the way": in his memoirs (the excellent two—volume "YO" was published a couple of years ago by GARAGE publishing), he invents himself, creates a vivid image for posterity, but this confuses researchers - it is still possible to understand the facts, but Eisen's feelings and motivations are unlikely. Even after death, he hides behind masks.

It is not surprising that attention to his figure is being paid right now: the issue of the artist's responsibility for the fruits of creativity is a very relevant topic. And she is one of the main characters in the novel "Eisen". Art has no right to choose one side. Alas, my hero did not understand this; throughout the novel, he searched for the main "philosopher's stone" of art — the secret of power over the viewer — but could not find it.

"I'm experimenting exclusively with structure and content"

— Your book is being published simultaneously in audio form, and negotiations are probably underway to adapt it to the cinema screen. Today, many more great novels are being turned into graphic novels. How promising do you find the various "alternative" forms?

— I really love graphic novels and comics, and cinema was born out of them. And many hundreds of drawings by Sergei Eisenstein for the film "Ivan the Terrible" may well make up such a novel. (Once in my youth, by the way, I was so impressed by these drawings of his that I hung them over my bed.) Eisen painted all his life, worked as a theater artist in his youth, and later his love for graphics turned into a director's profession.

The novel "Eisen" is written on the border of literature and cinema, imagery is an important component of its formula. So I think it's quite possible to translate it into a graphic novel, as well as to film it. But if you're going to fantasize to the fullest, then I think the best idea is an animated film with movie quotes inserted.

— On the one hand, your novel is certainly cinematic. Sometimes it even feels like you were trying to transfer to paper the techniques of "mounting attractions" that you write about in connection with the "Strike" and "Simplicity is enough for every wise man." On the other hand, the narrative is very traditional in its general structure and inherits in this sense the traditions of great Russian literature. Do you think the classic novel form will remain relevant in the future, in 20-30-40 years, or are we waiting for some kind of genre transformation — for example, the transformation of books into a kind of multimedia journey? Maybe you plan to experiment in this direction yourself?

— So far, I'm experimenting exclusively with the structure and content of novels — I'm trying to create each one so that the structure of the book grows from artistic goals, from the development of the hero and the theme. As the classic said, "every novel is an experiment." Of course, in "Eisen" everything is determined by the main character, including cinematography, editing, and other techniques of the Master.

— Are you aware of any plans to publish Eisen in other languages?

— 13 transfer agreements have been signed today. I hope that in the next year or two "Eisen" will be released in English, French, German, Italian, Spanish, Turkish, Arabic and other languages. Some translators have already started working.

Eisenstein is perhaps the most famous Soviet director abroad. And the theme of an artist's responsibility for his work, for justifying violence, for turning into propaganda, is universal and knows no boundaries.

— How do you move from one idea to another? Here's the "Eisen" out. Have you already started working on a new novel, or maybe this work was going on in parallel with the writing of "Eisen"? Can you tell us what the next book will be about?

— It is difficult, even impossible, to develop two topics in parallel. Right now, my head is still occupied with Eisen, since the book has just come out of the printing house, I haven't even picked it up yet. There are a couple of months ahead that we need to devote to this newborn baby, hold presentations and meetings with readers. And then you can think about a new topic.

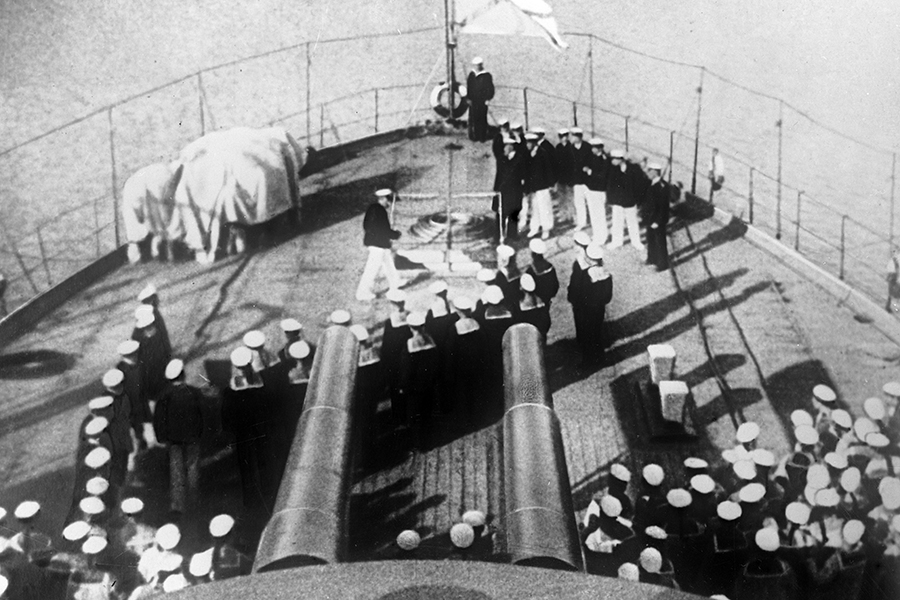

At the end of the interview, and to rhyme with my answer, let me tell you a funny story from Eisen's life. Few non-specialists know that Eisenstein wrote the script for Battleship Potemkin in parallel with the second libretto, based on the stories of Isaac Babel. Money was really needed, and the young energy was quite enough for such a split: in the morning to invent revolutionary episodes, and in the evenings — from the life of bandits. But not only that! Eisenstein also took on a third parallel work, a script with the frivolous title "Bazaar of Lust" and with rather maneois content, about the everyday life of brothel workers. I did it. It turned out to be a very cheerful and fascinating thing, I read it in a review. This seemingly anecdote is a fact of Eisenstein's biography. And Eisen had such vivid episodes all his life.

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»