Tweeting in all weathers: Artists fighting for their art

Elizaveta Gazarova's book contains portraits of 14 artists, ranging from world—famous ones such as Konstantin Korovin and Valentin Serov, to undeservedly half-forgotten ones like Stanislav Zhukovsky or Semyon Nikiforov, who lived only 35 years. Critic Lidia Maslova presents the book of the week, especially for Izvestia.

Elizaveta Gazarova

"Russian Impressionists"

Moscow: Molodaya Gvardiya Publ., 2025, 364 p.

The representatives of Russian Impressionism had different starting conditions. Someone was born into a wealthy merchant family, someone into a poor peasant family, recognition came to someone easier and faster, someone achieved success longer and harder, but almost everyone had to overcome something (even their own character or other people's prejudices), defending their right to see the world As Konstantin Gorbatov, the last character in the book, who avoided realism, put it: "The art of painting is not a mirror of life, but a living, moving surface of water reflecting life in the most bizarre and unexpected ways."

Gazarova speaks about fleeting variability and iridescence as the main signs of impressionism in the preface, starting, of course, with the appearance of the French Impressionists in 1874, who "brought to the fore the feeling of the fluidity of life and the uniqueness of every moment with their picturesque depiction of the mobility of air and light." As features of the pictorial language, ways of "grasping" an elusive moment, the author of the book notes the impressionistic manner of selecting colors not on the palette (there is simply no time for this), but directly on the canvas, relying on intuition in the search for the right color, "quick plein-air writing with bold, sensual strokes with the expectation of the correct perception of the color system from a certain the distances...".

The art critic compares the new trend with the principles of the realist Peredvizhniki (Gazarova's previous book, published the year before last, was devoted precisely to the fate of the Peredvizhniki). In theory, the "luminous joy" of the life-loving Impressionists represented something opposite to the social accusatory pathos of the harsh and often gloomy Peredvizhniki, who rejected plotlessness and lack of ideas. However, even among them there were those who met the new trend not with hostility, but with enthusiasm, although at first with slight confusion.

For example, Ivan Kramskoy, who wrote to Ilya Repin, what you can learn from the Impressionists: "...there is something there that we need to wrap our heads around in the most diligent way — it's trembling, uncertainty, something immaterial in technology. <...> There are no contours, you don't notice light and shadow, but there is something caressing and warm, like music. The air will cover you with warmth, the wind will even get under your dress ...". Art critic Sergei Makovsky tries to express a similar feeling in the epigraph to the chapter on Stanislav Zhukovsky: "The artist conveyed more with paints than paints: he painted the wind" (about the painting "Windy on the Lake").

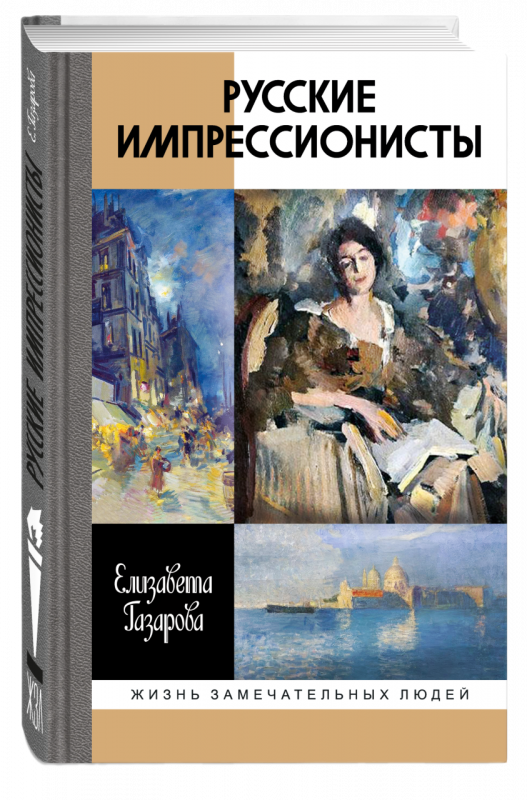

The living and moving surface of the water, which inspired Gorbatov, adorns the cover of the book, which features "Blue Morning. Venice", which captured Konstantin Pervukhin's beloved location, "Night. Marseille Embankment" by Abram Arkhipov and — the largest of all — a fragment of Konstantin Korovin's "Portrait of a Woman" from 1912. Korovin, as one of the most status figures, is devoted to the first chapter, where the psychological portrait of the official founder of Russian impressionism turns out to be very charming and effective, but not devoid of a peculiar "double bottom" — like the famous portrait by Valentin Serov, where Korovin lies with a sly look, leaning impressively on a pillow in his studio.

From an art historian's point of view, Korovin is a spontaneous impressionist, unfamiliar with "optimistic French painting saturated with light and air," but intuitively gravitating towards the same thing due to his mental structure.: "In the gardens of his art, he fluttered like a light, elegant butterfly, collecting the nectar of harmony and beauty from the wondrous, sun-caressed flowers of life." From the reviews of people who knew Korovin, the image of a charming moth, a host and a buffoon, who also possessed the valuable ability to sit elegantly on two chairs if necessary, develops. "Konstantin Alekseevich's element is compromise, and here is the result: he is equally willing to offer his works to exhibitions of art lovers and expositions of 36 Artists," Gazarova writes, describing the atmosphere of rivalry between the St. Petersburg World of Art association and the Moscow society of 36 Artists. The image of the charming conformist Korovin is completed by the review of his fellow student Mikhail Nesterov.: "Kostya, like a chameleon, was changeable, then he was diligent, then lazy, then charming, then obnoxious <...>. Everything in him lived, flourished and flourished" — in general, the ideal, as they would say today, the ambassador of impressionism.

Gazarova passes from Korovin to Valentin Serov, who is in many ways the opposite of Korovin in human terms, which, however, did not prevent their long friendship, as Serov's daughter Olga testifies in her memoirs: "Dad loved Korovin dearly, especially in his youth, loved and appreciated his exceptional painting talent, and forgave him a lot, which I wouldn't have forgiven anyone else." Serov, who was talking to himself: "I'm still, if you'll excuse the expression, a realist," stands somewhat apart from the Impressionists. According to Gazarova, Serov's individual style never fully submitted to "neither the elusive understatement of Impressionism, nor the refined ostentation of aesthetics, nor the free arrogance of modernity ...".

In the Serov chapter, verbal vignettes of a somewhat stilted shade appear more and more often on the pages of the book: "a magic crystal of incomparable artistic intuition", "muslin of artistic understatement", "high aesthetics of creative utterance", "diamond facets of lively sophistication". However, these old-fashioned phrases have their own charm. Recalling how one of her contemporaries called Serov "an artist of the spoken word," Elizaveta Gazarova also strives for a highly artistic style and sometimes likes to emphasize her lexical old-fashioned, ironic over modern words: "as they would say today, charisma" (about Igor Grabar's grandfather Adolf Dobryansky, a Slavophile who fought against the Magyarization of Ugric Russia), "as they would say today, creative" (this is already about the bold and free activity of Grabar himself as a trustee of the Tretyakov Gallery).

There was also a place in the book for opponents of impressionism, whose adherents, both in France and in Russia, at the beginning of their struggle for novelty and originality, sometimes had reason to fear that traditionalists might mistake them for lunatics. One of the main haters of impressionism is the critic Abram Efros, who is associated with an expressive episode: Stanislav Zhukovsky, who was pejoratively declared a "singer of noble life" in the early 1920s, comes to the editorial office of the Theater Review and slaps Efros with a magazine with his own devastating article, after which he soon emigrates to Warsaw.

In the chapter on Leonard Turzhansky, Korovin's favorite student, Gazarova quotes Efros's review, which can be seen as a mockery of the indestructible joviality of the Impressionists: "They were lyricists and tweeted in all weathers," a critic spoke with contemptuous condescension about Turzhansky and other painters who did not abandon the artistic motifs of the past in an era of aggressive restructuring of life and art". However, for some reason it seems that Efros, who was not so simple and also knew a lot about creating the right impression, actually cunningly praised the Impressionists, pretending to scold. After all, the ability to sing easily and naturally, like a bird, regardless of the aggressive environment, is quite an enviable quality for an artist.

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»