From wide trousers: how art from different eras described personal documents

The main conflict that Patrick Bixby, a professor at the University of Arizona, traces in his book on the history of passports is the irreconcilable contradiction between the sense of individual sovereignty and the protection of state sovereignty. It is the passport that best embodies this conflict, "embodying independence and mobility, adventure and opportunity, freedom and safe haven, it is also an instrument of state supervision and control of the authorities." Critic Lidia Maslova presents the book of the week specifically for Izvestia.

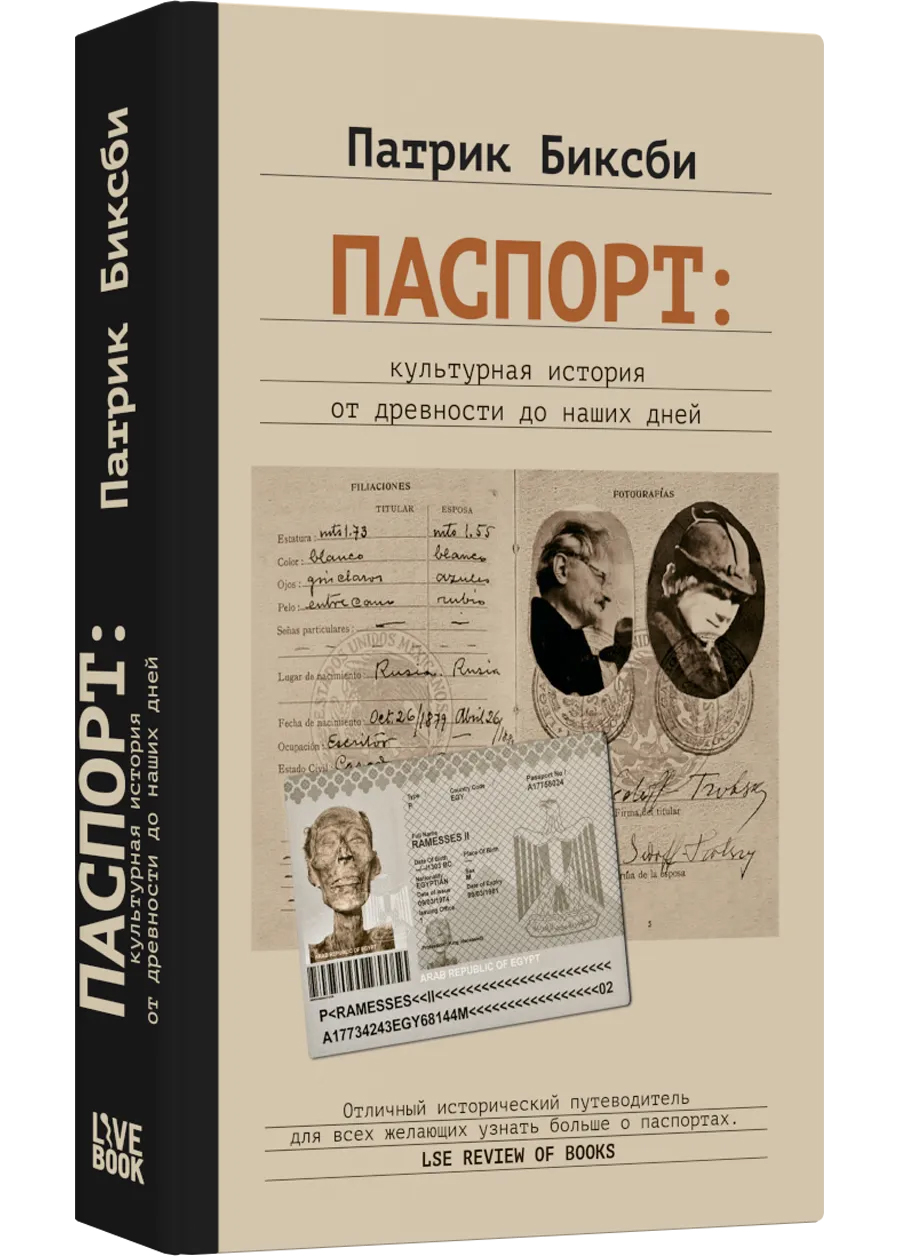

Patrick Bixby

"Passport: cultural history from antiquity to the present day"

Moscow: Livebook Publishing House, 2025. — [Trans. from English. Daria Ivanovskaya]. - 400 p —

However, the author's general theoretical arguments relate to the passport as an abstract socio-cultural concept, but in practice, as always, a lot is decided by geopolitical nuances (which country issued the passport) and the human factor (to whom, by whom and how issued), so the passport is different from the passport. The first of Bixby's cultural heroes and famous wanderers to illustrate this idea is the writer Salman Rushdie, who felt the difference between an Indian and a British passport as between "worthless" and "effective": "The writer keeps vivid memories of his first Indian passport, which he had in the 1960s; It had a painfully short list of countries that were allowed to visit. When he received a British passport as a teenager, it seemed to him that the whole world opened up before him, and soon this little book took him far from home, to Cambridge education..."

The journalistic epilogue "Good" and "Bad" Passports" is devoted to inequality in the international passport system, where Bixby is forced to state that utopian dreams of a world without borders, without a global hierarchy of haves and have-nots, are currently hardly feasible.: "The United Nations may proclaim that 'everyone has the right to leave any country, including their own, and return to their own country,' but in fact not all passports are equal and not everyone is treated with equal respect."

A photo of a page from Rushdie's respected and effective 1974 British passport is the first illustration in the book, where you can also admire the travel documents of James Joyce with his wife and two children (by making one passport for all, the Joyces saved 5 shillings, and in 2011 it was sold at Sotheby's for £61,250), Hannah Arendt, Leo and Natalia Trotsky, interplanetary traveler Thomas Jerome Newton, played by David Bowie in the movie "The Man Who Fell to Earth", and even Pharaoh Ramesses II. We are talking about the "artistic version" of Ramesses II's passport, which was made by some online pranksters in 2020 by pasting a photo of a mummy from a museum catalog into an Egyptian passport and filling in all the required fields, including not only the date of birth (-/-/1303 B.C.), but also a profession: "The king (died)."

Behind this photo is a bureaucratic story that allegedly happened to the Pharaoh's mummy during its transportation to France for restoration in 1976, when Ramesses had to issue a passport for a number of legal reasons (international law does not allow transporting human remains without proper identification, French laws require that anyone entering the country, even the dead, have he kept a passport for himself, and Egyptian officials believed that the Pharaoh would be safer abroad with a document). However, Bixby clarifies that Ramesses II's real passport has not been found in any archive, and perhaps we are dealing with some kind of hoax or an example of collective false memory, the so-called Mandela effect.

Egyptian motifs in a similar curiously absurdist perspective are continued in the third and final part of "Passport as we Know it", in its last chapter "Strangers and Autochthons", where among the various originals who practiced an unconventional approach to handling a passport, there is an experimental jazz musician and afrofuturist, a native of Alabama, who worked under the pseudonym of San Ra. This multifaceted personality was not limited to music: the book contains a delightful retelling of the feature—length film "Space is a Great Place", which San Ra and his companions shot in 1974. This sci-fi blaxploitation offers "a grandiose plan to spread the African diaspora to the far corners of the Galaxy." San Ra himself acts as an intergalactic ambassador who is threatened with violence by racists from NASA, but the alien still manages to teleport some of the black earthlings to his ship and escape from a planet mired in racial injustice.

In principle, a separate film could have been made about how in 1970, San Ra, preparing for a European tour, turned to the New York passport office for his first travel document, in which one could read something that Ramesses II would have spun with envy in his tomb. The first clerk, to whom the musician introduced himself as "San Ra from Saturn," requested all sorts of boring additional information from him, such as the date of birth and the names of his parents, which the petitioner refused to provide. But in the evening of the same day, another, more liberal employee, probably reasoning that it was easier not to mess with a madman if he was not violent, nevertheless issued San Ra a passport, putting Saturn in the "Place of birth" column.

The most famous character in the book who can defy bureaucrats is Elon Musk, whose story, Bixby writes, "like many other immigrant stories, also rests on a passport." The book describes in detail the difficult vicissitudes that allowed Musk, who was born in South Africa, to gradually move to America, as well as his rapid career rise, from the height of which he could already criticize the excesses in immigration policy made by the first Trump administration. As Bixby writes about the Mask, it is quite possible to suspect the alien origin of the founder of SpaceX corporation: "Here is another outsider who came to the country with simply supernatural talents, made a huge fortune thanks to his technological abilities and now dreams only of leaving Earth on a rocket of his own design in order to bring life to Earth. A seemingly uninhabitable planet."

But even if Musk, with his supernatural talents, manages to carry out his plan to colonize Mars, ordinary space travelers will still need the same passports and visas that cause them so much trouble on Earth, warns Bixby, who soberly looks at the situation when the earth's passport system is far from perfect: "A futuristic fantasy about Martian colonies are perhaps more plausible than the cosmopolitan dream of a world without state borders, and therefore without "illegal" foreigners and international strife that may require a planetary escape plan."

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»