Good-natured bohemia: Andrei Voznesensky's widow recalls the past

The memoirs of Zoya Boguslavskaya, the widow of Andrei Voznesensky, who recently celebrated her 101st birthday, are made up of notes from different times, not always arranged chronologically (from 1999 to 2021), and of a different nature. Somewhere the diary's intimate intonation sounds clearer, somewhere the official component of Boguslavskaya's life as a public figure, who stood at the origins of the Triumph Award, comes to the fore, to which several special chapters are devoted. Critic Lidia Maslova presents the book of the week specifically for Izvestia.

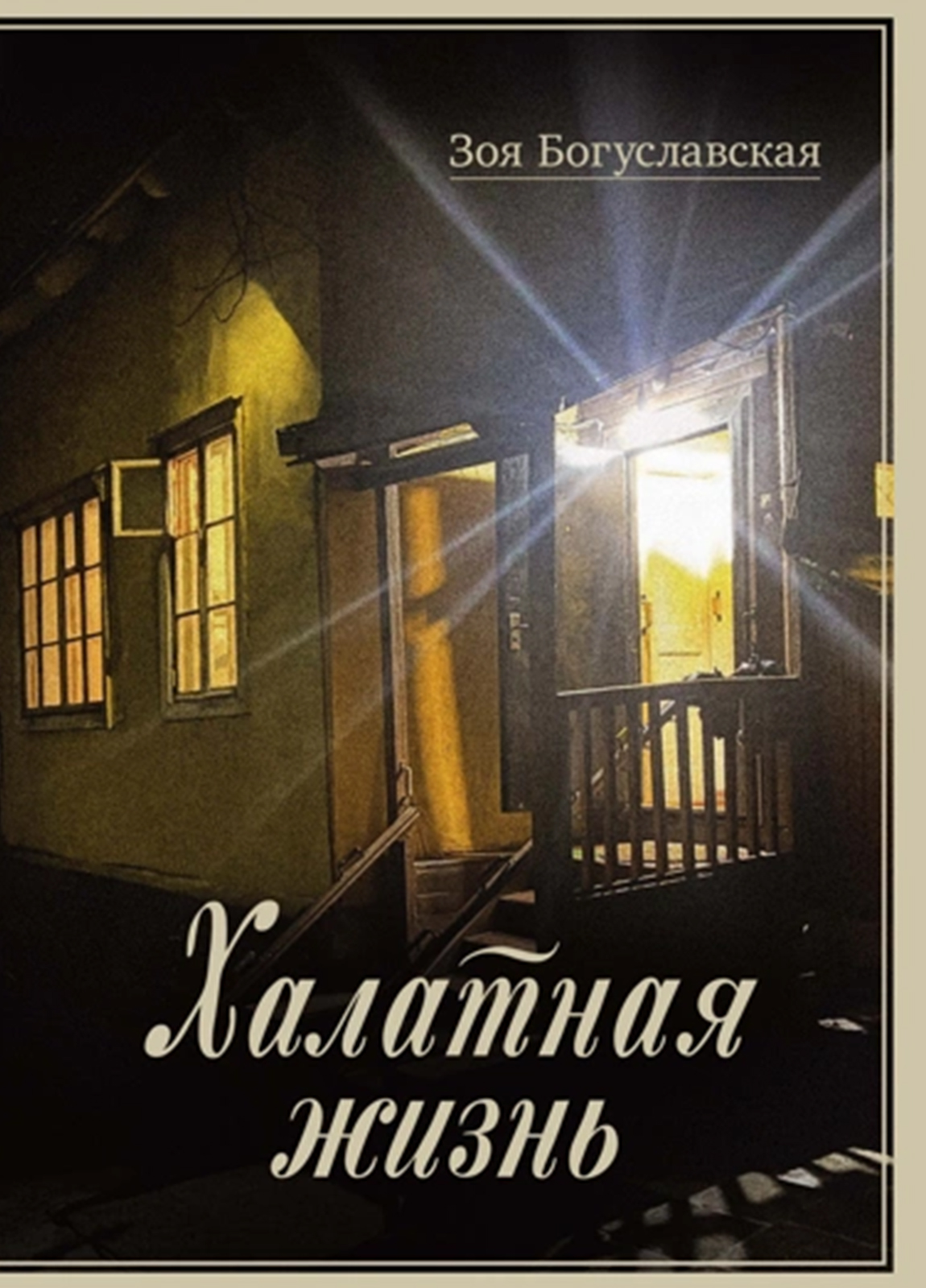

Zoya Boguslavskaya

"Negligent life"

Moscow : KoLibri, ABC-Atticus, 2025. 528 p.

Zoya Boguslavskaya once planned to start the book of memoirs "Negligent life" with the phrase "I have three dressing gowns..." She later abandoned this idea, however, the bathrobe appears in the margins towards the end of the book as a symbol of a certain slowing down of life, its "waning", when in the final chapter "Without results, or What is happiness and what old age is" the author argues that old age is "when you spend most of your time in a bathrobe," being able to calmly indulge in philosophical reflections at home and not being burdened with the need to receive guests or rush out somewhere on business. But immediately Boguslavskaya adds: "When I see a robe that fits me well, I am already a slave to this purchase," confirming that indomitable femininity, associated with the desire to look spectacular in any situation, is beyond the control of any age.

"Negligent life" is an extremely feminine book in the broadest sense of the word, with all the purely feminine advantages and disadvantages: emotionality, proud passion, heightened author's sense of self—worth, often bordering on coquetry, hidden resentments, subjectivity of assessments, but imbued with fascinating vitality and valuable as a large-scale sketch of a huge era.

But in such a "happy, long, dazzlingly interesting" life as Boguslavskaya describes, the personal and the public are already difficult to separate. 46 years of this life were spent married to Andrei Voznesensky, one of the Sixties icons, the number of which Boguslavskaya sometimes outlines strictly, quoting her husband's poem "There are few of us, there may be four of us" ("Some believed that this was Okudzhava, others that this was Robert Rozhdestvensky. The three are Bella, Andrey himself, and Yevtushenko. Most likely, Andrey himself did not want to designate the fourth one"), and sometimes expands it by adding, for example, Vasily Aksenov to it.

And Nikita Khrushchev, perhaps, becomes the main antihero of the era — many pages of bitterness and anger are devoted to his meeting with the creative intelligentsia on March 7, 1963 in The Negligent Life. The famous Khrushchev cry is repeatedly heard in the book as a traumatic refrain: "Do you think you have a thaw?! You don't have a thaw anymore. Reading how Boguslavskaya returns again and again to this scandalous episode and to the image of 29-year-old Voznesensky, insulted by Khrushchev's bossy rudeness, one begins to guess that perhaps it was at this moment, witnessed by a shocked Boguslavskaya, that the transformation of friendly relations between the poet and his future muse began. more: "This episode left not only bloody marks on Andrey's state of health, but also many lines in his poetry. His experience was reflected in the poem "Oz": "When troubles fumigated me, I dived under the Rig like into water, you gave me your breath through a blond straw," and many others."

Vasily Aksenov's novel "The Mysterious Passion", which presents an ambiguous view of the Sixties, and the series based on it, which became sensational at the time, become a reason for controversy and clarifications by Boguslavskaya. She admits that the era in the film is shown well, but finds it necessary to correct important moral and ethical points: "Yes, we were bohemian, but it was Soviet bohemia - it was moral, much, much more moral than the current one. First of all, no one betrayed anyone there. Secondly, if one of us was harassed or harassed, then everyone closed in around him, stood up for him. We were excluded from everywhere, but we knew what we were going for, it was an unusual bohemian."

In addition, in the film, according to Boguslavskaya, the Sixties say a lot: "But we were secretive, we didn't share any novels or adventures." The memoirist talks about her own novels quite frankly, but chaste: "... I've actually had seven men in my life. A little bit for the bohemian environment I lived in. Three of them are legitimate husbands. I had a friend at GITIS, a plain girl, who went all out, and she said that it was easy for her, to whom no one offered anything, to be virtuous, but Zoika Boguslavskaya, who had no end in sight, was virtuous without fools."

As a memoirist, Boguslavskaya can be seen to have many virtues — for example, a combination of observation and restraint, which sometimes prevents the resentment bubbling inside of some petty, ridiculous, aesthetically flawed human manifestations from breaking through. A secular lady of good upbringing and strict rules, who should always look comme il faut (even in a bathrobe), most often defeats a writer in Boguslavskaya, who, perhaps, would like to put an unpleasant red word in someone's address. In the end, Boguslavskaya admits that life and communication with people turned out to be more important to her than literature, that life still won in constant competition with creativity, closer to the finale: "...I do not consider myself a genuine writer who cannot live a day without a line, for whom writing means living. <...> The "proposed circumstances" have always been brighter than what my consciousness produced when I wanted to sit down and put something into words."

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»