Whip and carrot: how Yuri Lyubimov staged "The Master and Margarita" in Sweden

The book by translator Lyubimov Leila Alexander-Garrett provides an inside look at the rehearsal process at the Royal Swedish Drama Theater, which the aborigines call "Dramaten". Here, in October – December 1988, Yuri Lyubimov, the director of the Taganka Theater, who emigrated from Russia, is trying to reproduce at least partially the staging of his most famous play, The Master and Margarita, irritated by the flat logic of local actors and their misunderstanding of some of the simplest things obvious to a Russian fan of Bulgakov's novel. Critic Lidia Maslova presents the book of the week specifically for Izvestia.

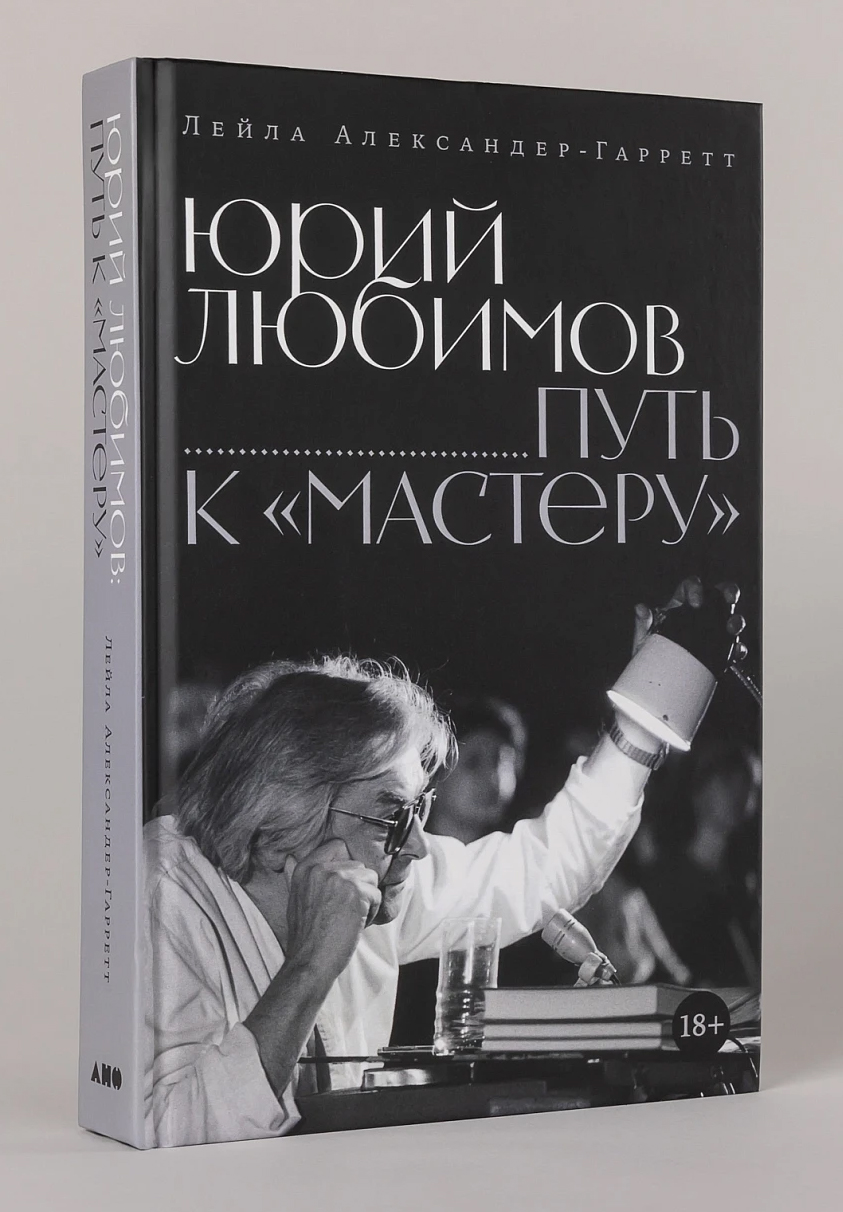

Leila Alexander-Garrett

"Yuri Lyubimov: the path to the "Master"

Moscow : Alpina non-fiction, 2026. 454 p.

The rather despotic director appears in the translator's memoirs as an extremely incendiary and colorful person, no matter how you treat her. And Alexander-Garrett herself does not always have unambiguously positive emotions for the hero of her book, sometimes allowing herself to be quite justifiably feminine emotionality and touchiness: at the beginning of the book, perhaps, a lot of space is devoted to the not very beautiful story of Leila's unexpected replacement with an Israeli translator during Lyubimov's work on the production of The Ring of the Nibelung in London Covent Garden. "I was overwhelmed by despair, tears, bitterness and resentment," Alexander—Garrett laments, recalling the sudden termination of the contract, but little by little he still finds the strength, if not to understand and forgive, then at least to come to terms with the unpredictability of Lyubimov, the brightest representative of that human breed, which is not always the case. It's easy and pleasant to communicate, but then there's something to remember. In addition, various literary allusions and associations are very well strung onto such ambivalent figures with whom love–hate relationships develop, and not only Bulgakov's, which, of course, are enough in the book. So, listening to Lyubimov's interpretation of Koroviev's image ("He's a mischievous man, he's bored, he's having so much fun"), Alexander—Garrett immediately gladly extrapolates it to Lyubimov himself: "It flashed through my mind that our director is the same prankster who does not tolerate boredom."

In order not to die of boredom with overly rational and straightforward Swedes, Lyubimov often performs almost like the entertainer Georges Bengalsky, gushing at rehearsals with memoir sketches, small lectures on Russian and Soviet culture, and even slightly bearded Soviet jokes, probably even taking special pleasure in the fact that the actors are not dramatic. They always get the joke. Alexander-Garrett defines one of Lyubimov's favorite genres as "A little gossip to distract and amuse the actors," but the long-lived director's repertoire also includes unique personal memories that must have made no less fantastic impressions on the Swedes than the adventures of the devil and his henchmen in Stalinist Moscow.: "To everyone's surprise, Lyubimov recalled that in 1924, as a seven—year-old boy in the fierce January frosts, he and his brother attended the funeral of Lenin himself, the leader of the Russian revolution. The actors gasped! "Yes," Lyubimov confirmed, not without pride, "as a boy I saw Lenin in a coffin." In addition, Lyubimov sometimes tries to overcome not only the difficulties of translating the novel (which not all the participants in the play mastered from cover to cover), but also the difference in mentalities, explaining the specifics of the Russian character to the Swedes in an intelligible or even provocative way.: "Everyone in Russia is a writer. In Moscow, everyone writes: some poems, some novels, some denunciations."

Alexander-Garrett is silent about how good the Stockholm version of "The Master and Margarita" turned out (during the work on which the wayward director had big questions for the performers of both title roles), but still, immersion in the rehearsal process allows the reader to imagine with imagination what the legendary Taganka performance might look like, which was bursting the audience in 1977, and what kind of set design decisions did its creator have a weakness for. Lyubimov's dislike of Stanislavsky's system as the cornerstone of his directing is covered in detail and in many ways in the book, especially since this is one of the main points of Lyubimov's ideological intersection with his idol Bulgakov, with whom the director sometimes tries to establish an astral connection: "I need to establish a connection with Bulgakov. You too. I'll talk to him at night and come to the rehearsal in the morning with his instructions."

Setting the Swedish actors' minds straight and trying to rouse them, Lyubimov spares no effort, no time, no eloquence to once again debunk such a mossy idol as Stanislavsky seems to him with his "method": "Lyubimov continues his speech about his non-recognition of the Stanislavsky system. He calls Bulgakov his ally, who also claimed that there is no system and there cannot be. You can't force a bad actor to play well. Yuri Petrovich says that in the unfinished brilliant "Theatrical Novel" Bulgakov publicly defamed the Stanislavsky system and exposed the theatrical backstage of the main theater of the country." However, Lyubimov's own methods are not much more complicated than Stanislavsky's concept, at least in the transmission of his devoted (though sometimes rather ironic) translator: "Lyubimov often told me during rehearsals that the strictest discipline and strict subordination should prevail in the theater team. Familiarity is absolutely unacceptable. A good director should always have a whip and a carrot in his pocket. A director is a trainer who deals with dangerous wild animals."

In the book, however, Lyubimov himself looks the most dangerous, whom Andrei Tarkovsky warned Leila Alexander-Garrett about while working on Sacrifice: "Where Lyubimov is, there are scandals!" And there is something infernally demonic in Lyubimov's characterization, given to him by Veniamin Smekhov (who played Woland on Taganka): "Lyubimov himself is an uneducated director. He's one of the actors—sweet, pretty, more or less successful, average talent. Lyubimov is uneducated in the field of painting, fine art — everything was picked up from his intuition. He is not a musical person, he has no hearing. In the field of literature, he is also more learned than well-read. <...> He gathers a performance, hears everyone, turns what someone has done into something else... Then suddenly we enter a period when he doesn't listen to anyone, but begins to cover, edit, assemble, compose, rebuild and fix. Then there's the dress rehearsal. It seems to him that this is a failure, but the audience comes — a triumph! Fantastic! Almost everything is wrong, but it's magic!"

In order not to inflame unnecessary demonism, Alexander-Garrett puts a little more benevolent touches on Lyubimov's portrait in the finale, resorting to a quote from Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh, who distinguished "fire" and "light" as philosophical concepts: "Fire burns in a young man; light shines in an old man. One must be able to burn while the fire is burning; but when the burning time has passed, one must be able to be the light."[Gorenje] This also has a bit in common with Bulgakov's novel, which ends with the idea that the burned-out Master did not deserve the light, but deserved peace. But peace, it seems, is the last thing that would agree to accept from the higher (or lower) Lyubimov's powers, as Alexander-Garrett describes him, are formulated in the finale of his book as either a compliment or a reproach: "It seems to me that Yuri Lyubimov did not make the transition from creative power to contemplative light: he burned and created until the last days of his life."

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»