The Bird of God Bites: The Emotional Ups and Downs of Birdwatcher

Published in 1967 and becoming a classic of British landscape literature, John Alec Baker's book "Peregrine Falcon" is experiencing another surge in popularity and is being published for the first time in Russian translation. Critic Lidia Maslova presents the book of the week specifically for Izvestia.

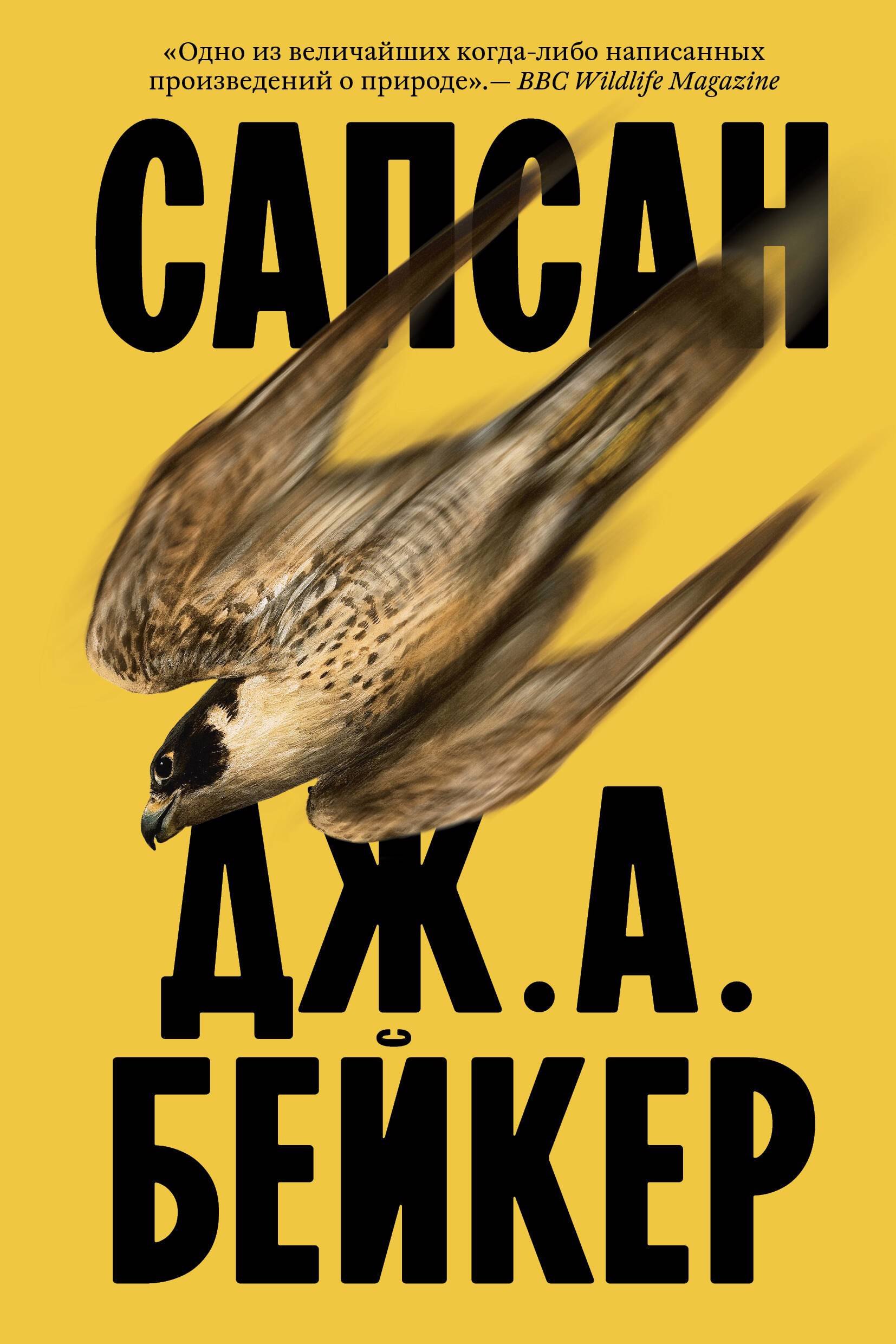

J. A. Baker

"Peregrine Falcon"

M.: Individuum, Eksmo, 2025. — translated from English by I. Maslennikov under scientific editorship by Yu. Mikhnevich — 272 p.

It seems that the main difficulty for the translator was not so much the accuracy of ornithological terms (this is carefully monitored in the footnotes by the scientific editor), as a reflection of the author's extraordinary personality and his original perception of wildlife. And John Alec Baker, apparently, was no less a rare bird than the peregrine falcon, which was on the verge of extinction during the work on the book, which took 10 years. As Robert MacFarlane tells in the afterword to Peregrine Falcon, a few months after the book was published, Baker received a £1,200 prize from the Arts Council of Great Britain, as reported by the Daily Telegraph newspaper, calling the writer the most unusual of the laureates, who "lives in a council house in Essex county, but does not disclose which one." He lives in the city so that the neighbors don't find out about his activities. He doesn't have a phone, and he never leaves his apartment."

Over the course of 10 years of field observations, the reclusive Baker, although married, but who had the opportunity not to be too distracted by social life, collected much more material than was included in the book. This is a rare ability for a writer to cut off all that is superfluous, excessive, which interferes with the main task, the main message, which in Sapsan is more poetic and philosophical than natural science or environmental. "Baker not only consciously compressed and modified the time frames of his works, but also deliberately erased toponyms and recognizable natural landmarks from them... Having cleared the text of excessive details, Baker wrote a mythical story of the search for a mythical bird — a story that both knows no boundaries and remains authentic," Mark Cocker notes in the introductory article to the 2010 edition, rewriting several prose lines of Baker in the form of a poem so that the reader can also admire the melodiousness of the language.

Written in a column, the lines of "Sapsan" do indeed resemble the poems of one of Baker's idols— Ted Hughes. John Fanshawe speaks about the undoubted intersection of their literary methods in the accompanying article. He provides a comparative analysis of Hughes' poem "Blackbirds" ("They catch and pull out the writhing prey. / Without the slightest delay, without blunders, / Without sighs or hesitation") and the passage where Baker describes ruthless thrushes impaling earthworms on their beaks: "There is something completely cold about a thrush- in the way he listens endlessly for a long time, and then pokes through the grass carpet; his motionless eye remains blind to what he has done."

In Sapsan, there are a lot of such fearless murders and descriptions of the prey that the hero of the book has captured and eaten. There are minimal differences between them, but in general they are very similar, and on almost every page you can find something like this episode: "The jay flapped its paws, as if in a fit. All askew, she was falling. The earth finished her off. A peregrine falcon swooped down and took the dead bird to an oak tree. There he plucked and ate her, quickly swallowing the meat until all that was left of her were wings, breastbone and tail." Or even more cruel and naturalistic: "I can hear bone crunching, like pliers cutting through barbed wire. <...> I can hear feathers pulling out, flesh tearing, cartilage cracking and snapping. I see black blood dripping from the falcon's shiny beak."

However, the word "murder" in relation to this peregrine falcon feeding procedure, for all its brutality, does not look entirely appropriate: predators hardly reason in such human terms, although it is difficult for a person not to endow animals and birds with anthropomorphic features and soul movements, not to apply associations with objects of human life to wildlife. Admittedly, Baker is as cautious as possible in this sense and sometimes pulls himself together, for example, when he finds himself face to face with a peregrine falcon and tries to penetrate the bird's brain, but quickly realizes the hopelessness of the attempt: "The Falcon is kept on a narrow line between curiosity and fear. What is he thinking about? Does he even think? Such a meeting is new to him. He doesn't understand how I got here. I try to hide the pallor of my face. He's not scared. He looks at how the whites of my eyes are shining. He doesn't understand the staccato of their flickering."

In fact, the author of the book would not so much like to see something human in a peregrine falcon (this, from his somewhat misanthropic point of view, hardly compliments the bird), as, on the contrary, he would sometimes dream of feeling like a peregrine falcon himself. Baker felt the inferiority and imperfection of the human body all the more acutely because he suffered from myopia and rheumatoid arthritis, which over the years increasingly limited his motor activity. It is not surprising that the writer is so fascinated by the sight of a wonderful swift bird capable of diving at prey at a speed of 390 km/ h, and is not at all confused by some monotony of repeated descriptions of such a plan.: "For ten winters, I looked up at the sky and searched for these anchor shapes, cutting through the clouds, this crossbow streaking through the air. The eye becomes insatiable to the point of a falcon, searching for it with ecstatic passion. The peregrine falcon's eye also rotates and clicks when it sees a well-fed seagull or pigeon."

The book often gives the impression "that the peregrine falcon does nothing but eat," as the author himself admits: "He gets two birds every day and, in addition, mice, worms, and insects," explaining such a rich diet with the need for increased blood supply for the growth of new feathers. However, there are relatively few such base physiological motivations and details in the book, and describing the peregrine falcon's next flight for food, Baker finds a way again and again to push off from the mortal earth and soar to metaphysical heights, where the peregrine falcon does not just hunt, but follows its lofty divine purpose: "It aims at a distant bird, at fluttering white clouds." wings, and when she spreads out like a white blur under him, he may feel he has to strike. His whole nature was created for the sake of combining a sighting eye with a striking claw. <...> When suddenly he flew past, the flapping of his wings lifted me to heaven. There was some kind of fervent vivacity, rhythmic zeal in his swift, piercing, diving, careening, winding flight."

It's not for nothing that one of the most ardent fans of "Sapsan" is director Werner Herzog, who, out of reverence for this book, even abandoned the idea of its film adaptation: "We can say that transubstantiation takes place, a religious sacrament, and the observer almost becomes the subject of his observation, a falcon. The author, for example, describes how a falcon soars high, climbs higher and higher, becomes a dot in the sky, and then suddenly dives. And the reader and the author are also diving, as if we ourselves are turning into a falcon."

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»