Noises of Rage: Forbidden Books, Sounding Museums, and the Return of Krakauer

Women's stories, the glorification of wreckage, the birth of Nazism in movies, and sound mirages in museums — all the books from our July review are good for the holiday season in their own way. Some are suitable for cultural and tourist trips, some for lying on the beach or relaxing in front of the screen. Izvestia will tell you what is best for you to choose.

There was no such light in the world before the advent of N.

Oksana Vasyakina

After the large-scale form of the acclaimed autobiography trilogy, consisting of the novels "Steppe", "Wound" and "Rose", the writer Oksana Vasyakina began to lean in favor of small genres. Izvestia wrote about the book "What I'm Thinking About," which included various poetic and prose works. Now a new collection has appeared, however, more monolithic and conceptual in content. 11 stories are the stories of 11 women. In ten of them, the plot is almost the same: the narration is conducted on behalf of the heroine, who describes the life of her friend. The final text is dedicated to Vasyakina herself: reflecting on her age, childhood and growing up, she recalls the "Melancholy" of Lars von Trier. And in retrospect, we try on the tragic plot about two sisters on the verge of the Apocalypse to the rest of the book.

Vasyakina is called a feminist. And, perhaps, the very idea of such a collection really looks as appropriate as possible to this movement. However, when describing the life vicissitudes of her characters, the writer is not at all inclined to idealize them. Her heroines are not strong and self—sufficient, but weak, vulnerable, dependent on men, habits, and circumstances... They rent cheap apartments for two, hitchhike in the Crimea, hang out on dating sites and desperately try to find happiness. In most cases, unsuccessfully.

An apology for the wreckage

Sergey Khachaturov

The book by art historian Sergei Khachaturov attracts attention by its name alone. The ancient learned word from the philosophical lexicon "apology", meaning praise or defense, encounters here the unexpected everyday term "debris" — but this actually very accurately reflects the content of the work, which is equally paradoxical. The series of essays that matured in Khachaturov's many years of lecturing at Moscow State University traces the evolution of the ruins phenomenon from antiquity to the present day. What was the attitude towards the destroyed monuments of Ancient Rome in the Middle Ages? Why did the image of ruins become fashionable in the era of Romanticism? And why do modern artists interact with fragments of the past, creating paintings, installations and even works of sound art?

The chronological structure of Khachaturov's narrative is actually deceptive. You could even say it's ruined. This is not a strict academic narrative, but a deliberately fragmentary thread on which a variety of subjects are strung — not only from fine art, but also from literature (from Virgil to Brodsky), architecture, archeology, philosophy.… You can compare this to some ancient city, the features of which appear in the excavation area, but no matter how hard you try to assemble them into complete buildings, it will only be a figment of the imagination, the result of speculation.

However, it is precisely in the case of such a topic that the reader's consciousness gratefully accepts the gaps that leave room for fantasy and make one think about the eternal desire of the world for destruction.

From Caligari to Hitler. The psychological history of German cinema

Siegfried Krakauer

The book by the outstanding film theorist Siegfried Krakauer, dedicated to the pre-war German cinema, begins with a discouraging confession: "I am not at all interested in German cinema as such." This is, of course, guile: Krakauer's work, first published in English in 1947, brilliantly analyzes the films of Fritz Lang, Georg Wilhelm Pabst and other masters. But the truth is that purely artistic aspects are really less important for the author than sociology — the influence of cinema on society and vice versa. In other words, Krakauer identifies the processes that developed in German screen art between the two World Wars with what was happening to the German nation at that moment. A vivid example is the story of the creation of the tape included in the title of the book. The original plot of "The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari," a masterpiece of expressionism, was supposed to celebrate the rebellion of a young loner against power. But director Robert Wiene turns the story of screenwriters Hans Janowitz and Karl Mayer upside down, showing the characters insane: the picture becomes, in Krakauer's opinion, anti-revolutionary and conformist. "In its modified form, Caligari is no longer a work that openly expresses the feelings of the intelligentsia, but a film that panders to the tastes and moods of a less educated audience," the researcher is sure. It is the reader's right to agree with him or not. But Krakauer's sometimes very controversial and sometimes frankly outdated judgments are also interesting because he was a contemporary of his characters, and all these films appeared before his eyes. So we can say that we have an eyewitness account in front of us.

In Russian, "From Caligari to Hitler" was published back in Soviet times, but with bills, without an essay attachment, and most importantly, without the translator's name. In the new edition, these problems have been eliminated, and the authorship of the translation has been returned: this is Gennady Shmakov.

Hear the museum

Sergey Uvarov

Sergey Uvarov, a musicologist, teacher, film director, curator, and essayist, is a very young man who has already done a lot in various fields. In addition, he has been appearing in Izvestia as an author for many years. But even if he had nothing to do with the newspaper, we would definitely write about his new book anyway.

It differs quite a lot from Uvarov's previous books. They have always been literature for the elite, a heart-to-heart conversation with initiates. In a sense, esoteric works. This also applies to books about the work of Alexander Sokurov, where individual pieces may be unclear even to cinephiles, and a large collection of interviews with relevant Russian composers, where every conversation looks like encrypted correspondence from a secret society, and a fundamental work about Mikhail Matyushin, where even after visiting the corresponding high-profile exhibition (which was also organized by Uvarov), not everything is clear..

"Hear the Museum" is written in an unexpectedly transparent, precise, absolutely accessible language, it is open to the reader with any degree of training. Yes, Uvarov wouldn't be himself if he hadn't acted like Sokurov, who sometimes has implicit quotes in films. So here, too, the names and themes of past books are integrated into the author's reflection on what sound is as an object or element of an exhibition. Uvarov turns a series of short essays into a conceptual series where the knob of the imaginary volume turns towards complete silence. And this word, "imaginary," is very important here. In the book about composers, Uvarov put quaries everywhere so that you can read and listen at once. And he added more notes. And here we are talking about sound, but Uvarov seems to turn it into text. We read and hear everything without technical devices, we feel with some special feeling what is described to us. And we think together with the author, without being distracted by clicking on links or looking into encyclopedias to understand what is at stake.

You may not know about Marina Abramovich and Matthew Barney, your favorite Uvarov director, before reading — the author will still tell you exactly what you need to know about them in the context of his reflections. "The sound is aggressive." "Sound is vulnerable and defenseless." This is where the book begins, and there will be many more paradoxes that are both discouraging and presented as if we ourselves had once tried to think about it, but did not grasp this thought, did not continue. But Uvarov thought of it, and he will bring us to the final word "silence", he will do it respectfully, generously and very simply. This is a very mature and free book, you want to reread it and feel like a human being, and modern authors do not give us this right very often.

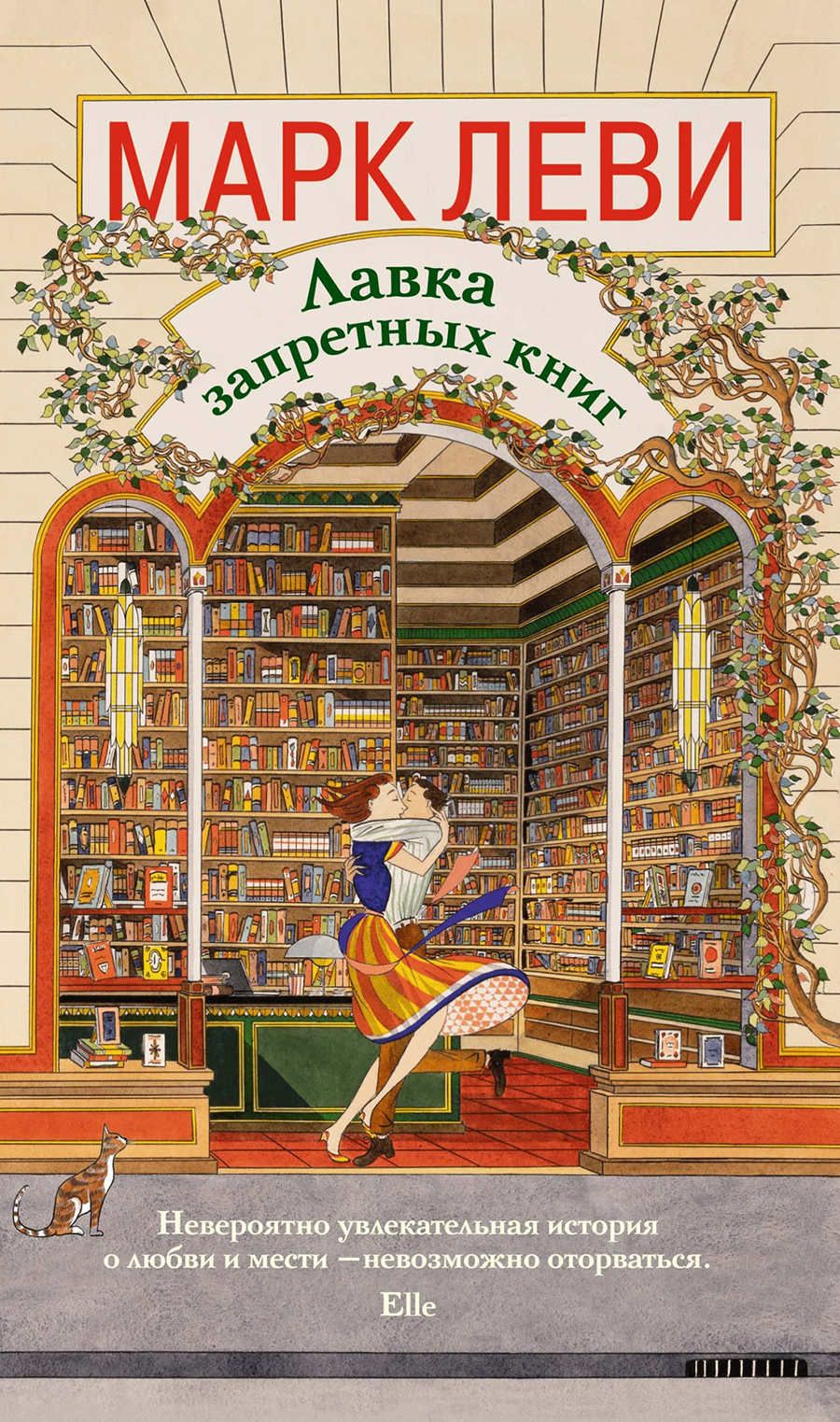

Shop of forbidden books

Mark Levy

When you read "The Shop of Forbidden Books," the new bestseller by French-American writer Marc Levy, you understand one thing very well. It's hard to write a dystopia today if you're a Western writer. That is, it will always be something somewhat naive, "light-hearted" and ultimately more soothing than warning of danger, sounding the alarm.

But "The Shop" is interesting to read, it skillfully handles the agenda and our fears, sometimes hitting just where it needs to be. The plot is based on a law that was passed in 2022 in the state of Florida, tightening control over children's and educational literature in public access. There were a lot of "no's" in it, and they say they began to remove books from school libraries where historical information was given "incorrectly", where it was "wrong" about racism, sex, and much more. It is not known how the Floridians coped with this reactionary censorship scourge, but Levy came up with a story about a new type of society. Here, bans have affected a huge number of books, and their sale has become a crime. For this, the owner of the small bookstore "sat down", who continued to distribute unwanted novels. The book tells about his adventures in full detail, but its general idea is this: you still need to spread, you need to read, you need to think — and then any totalitarianism will retreat and collapse. And Levi is so convinced of this that sometimes it gets really funny, even though he seems to have written it quite seriously. For some reason, I remember Bulgakov's about Kant and Solovki, but Levy probably didn't read it, otherwise he would have approached such an important topic more seriously.

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»