"I love women, but I've never been a womanizer."

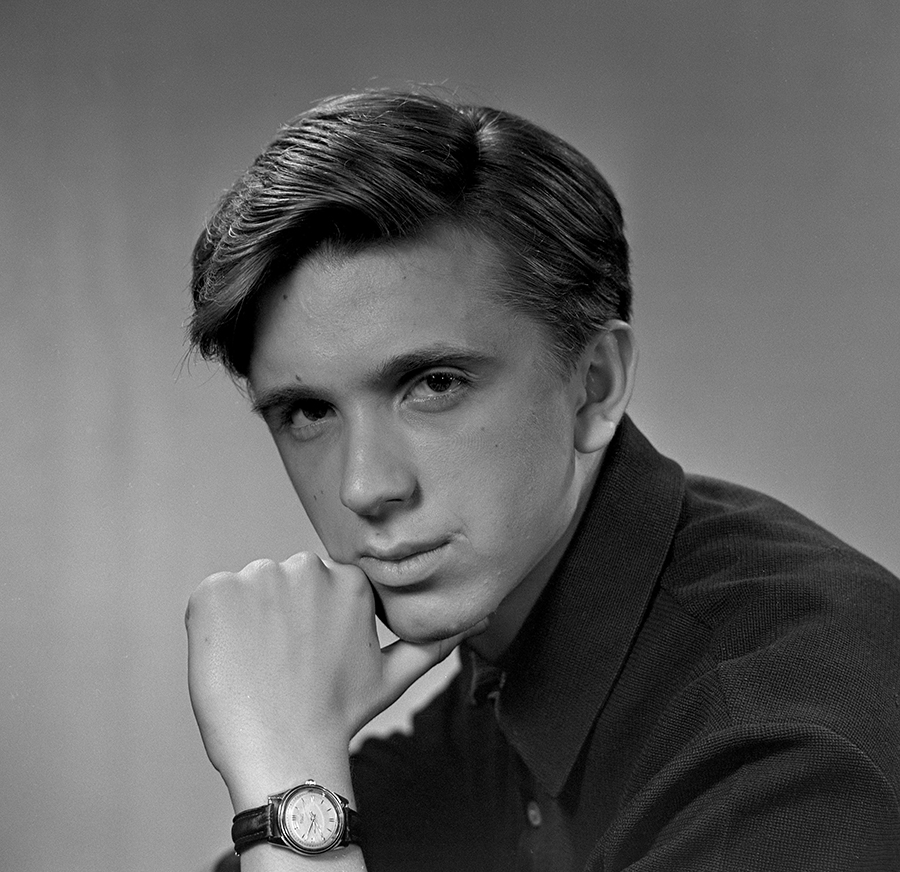

Filming in Georgy Danelia's film "I walk through Moscow" became a happy ticket to the profession for the young student, recalls People's Artist of the Russian Federation Evgeny Steblov. He got on the set almost by accident, but Nikita Mikhalkov already recognized Steblov as more talented than himself. Today, he has more than 35 theatrical works and over 50 film roles in his creative piggy bank. Evgeny Steblov spoke about his childhood in the criminal district of Moscow, about his son's desire to enter a monastery and fatigue from the acting profession in an exclusive interview with Izvestia on the eve of his 80th birthday.

"When there were fights in the yard, I was never beaten"

— We are talking on the eve of your anniversary. You act in plays, act, teach. How are you strong enough for all this?

— You listed everything correctly. The powers come from myself. And when they are, I work. I'm playing in two theaters now.: in my native Moscow City Council, where I have been serving since 1969, and at the Et Cetera theater with Sasha Kalyagin. Now everyone is adjusting to my schedule, so that's fine.

— If you look back from the height of your past years, would you like to change something?

"I don't think so. I am a religious person. As the Lord has ruled, so it should be. He has his own plan, and you need to live up to it. That's my approach.

— Are you a happy person?

— Absolutely. It's a sin for me to complain about fate.

— And what is happiness for you?

— Happiness is a human condition. It can be experienced on various occasions. But for a believer, life itself is already happiness. It is not given to everyone, and if it is given, one must be grateful.

— If you go back to the beginning of the journey, do you think acting was predetermined or is it a chain of coincidences?

— Randomness is an unknown pattern. I think everything is logical. Since childhood, I have been interested in theater and cinema. When I was little, I was engaged in puppet theater, then I got tired of it, and I went to a youth studio, then I entered the Shchukin Theater School.

— You once told me that Dad made you a screen for a puppet theater.

— Yes, my father made the screen, but I made the dolls myself. My parents were sympathetic to my hobby, helped and encouraged me whenever possible. Although they themselves were not from an acting background. Dad is an engineer, mom is a teacher. She worked as a school principal, then as deputy director of the Institute for Teacher Training. And my father worked at a closed defense enterprise — then it was called "working in a box."

— Were they not against your choice?

"Never." On the contrary, they helped and did not put obstacles.

— Your childhood was spent near Marina Grove, which is not the most peaceful area of Moscow. Did you encounter gang violence during your school years?

— I did not live exactly in Maryina Grove, but opposite the Riga railway Station. We thought it was a different neighborhood. The court was mixed: punks and intelligent people. I remember the atmosphere well. I wasn't friends with the punks, but we knew each other. They treated me loyally, and when I started acting in films, they were completely supportive. Many of them were in prison afterwards. But, thank God, the criminal side of life bypassed me.

It's funny to remember now: when there were fights in the yard, I was never beaten. I was an unsportsmanlike boy. I remember one of the guys saying: "Don't touch that." Later, I thought: maybe because my father built a TV in 1949 and people came to watch shows, you offend me, and they won't invite me to watch anymore. But I think it's not just that. I've always felt a certain chosenness—not socially, but internally.

"I'm walking through Moscow" is my star ticket"

— To what extent did the role in the film "I walk through Moscow" become fateful?

— I entered the institute early. I was only 16 years old at the time. For the first six months, I literally flew on wings with happiness. After all, it's an incredible piece of luck to legally do what you love! And "I'm walking through Moscow" is my star ticket.

Actually, I was in the movie by accident. My classmate Vitya Zazulin and I wanted to be noticed, so we went to Mosfilm without a clear goal. I don't remember how we got through the entrance, but we ended up inside. We met a friend from the evening faculty, who wandered through the pavilions to get familiar and get to the auditions. He advised me to go up to the fourth floor to watch the film "I'm Walking through Moscow." We were immediately shown to George Danelia. He told the assistant, "Vita needs to take a photo test, but this one—that is, me—doesn't need it."

But Lika Averbakh's assistant, a very talented woman with an amazing flair for actors, insisted on my audition. By the way, it was she who opened the Polish gallery for the film "Wild Dog Dingo". Later, Lika explained, "You looked so plaintive that I decided to try you too."

The photo tests turned out to be successful. Danelia has already approved another artist and even cut his hair, but after my auditions, everything changed. I later read in his memoirs how their conversation took place: that actor was shouting and swearing. As Danelia wrote, he even stopped stuttering — maybe that's how he cured him.

— Do you remember what acting tasks Danelia set for you?

— He didn't set any special tasks. The picture was shot easily. This was the case with other films that were later successful. I think my naturalness worked. I'm an organic artist, and I realized that pretty early on.

— In theater schools, they used to forbid students to act. Nikita Mikhalkov, they say, was expelled for this.

— At the Moscow Art Theater studio school, yes, absolutely. At the Shchukin College, which I graduated from, filming was not recommended, but there were exceptions — I am among them. The head of the school, Boris Zakhava, who, by the way, played Kutuzov in Sergei Bondarchuk's War and Peace, treated me kindly and let me go to the shooting without any problems.

He told Mikhalkov, "Either study or act," but he didn't kick him out. I remember Nikita telling me then that I was a better artist than him. I didn't think much of it. Then I realized that a director was already born in him. And he became an outstanding director. I am happy that we took our first steps together. We still have a good relationship.

— "Goodbye, boys" is a completely different picture. Was she close to you?

— Radically different. And it was hard. It's about the pre—war generation-my parents belong to it. Many of them went to the front from school and never returned. I felt a huge responsibility then. And our director Mikhail Kalik, an outstanding man, had a tragic fate: he spent three years in various prisons, then emigrated. On trips, he often thought about it, he told me: "You couldn't have stood it there." He emigrated as soon as it became possible. I've never had any thoughts of leaving. I can't imagine life outside of Russia.

— Many people leave "for a better life."

"I don't see a better one there." Of course, I've been abroad. It is interesting. But not to live. Where you were born, it will come in handy there. It is very important for me to be involved in my native land.

— Where do you feel most comfortable?

— In the village. I love the forest, the river. Resorts and heat are not my thing. I am a man of the middle lane. There is no way without Moscow, without the Moscow region.

"I'm already tired of acting somewhere deep in my soul"

— They say all actors are amorous. And you've been living with the same woman for many years.

— I love women, but I've never been a womanizer. He lived with Tanya Osipova for 38 years. She left in 2010. I've always been loyal to her. I'm not interested in cheating on the woman I love. She didn't take my last name, and decades later she regretted it. When I was making her gravestone at the Troekurovsky cemetery, I wrote: "Osipova-Steblova". I think she would be pleased. I am absolutely happy in the family plan. I have a son, now Father Photius. He went to a monastery.

— How did you make his decision?

— How could I not accept it? If I was against it, it would only ruin the relationship. They have remained close to us. He studied at the acting faculty at the Shchukin College, starred in the main role in the film "Eyes". He understands me creatively and in a human way. The difficulties were only during my second marriage, which turned out to be unsuccessful. The son then cooled down, but after the divorce everything got better. He never charged me with anything.

— Has life given you a stronger sense of drama than cinema?

— I have been teaching for many years and I always tell students that life is more important than art. There is a position that art requires sacrifice. But I think that personal is more important than acting. When a person does not have interesting content, an inferior artist leaves the walls of the institute.

By the way, I've published a book called "Who are you friends with?" — this is the fourth edition. I have always written with great pleasure. I'm already tired of acting somewhere deep in my soul. But writing doesn't. But I'm an impulsive person, and the writer is a long—distance runner. So I can't completely go into literature.

— What life principles do you adhere to?

— Christian ones. I try not to sin, to repent, to admit mistakes. Life is more important than art — I repeat this. Going through conflicts and harmony, the artist must process everything with his soul and give out a positive. That's why I don't like playing negative roles. They're easier to play, but that's not my thing.

— Are you more of a theater or cinema artist?

— I've been working there and there all my life. After graduation, he dreamed of joining the Lenkom Theater, which was then directed by Anatoly Efros. He looked at me and accepted me, but we didn't work for long: I was drafted into the army, then he was gone. He's one of my teachers. Later, Efros worked at the Mossovet Theater, staged the famous play "Next is Silence" with Rostislav Plyatt and Faina Ranevskaya. I was lucky enough to partner with her in various productions.

You know, I've been sitting on two chairs all my life — both theater and cinema are equally important to me. Theater is a home, cinema is an adventure. I'm more of a co-author than a performer in my work, so it's important for me to match my worldview with the director. Not because I'm prying into authorship. It's just that I'm a writer, and I inevitably bring something of my own to a play or movie.

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»