Brodsky and Osya were here: a nephew's memories of his uncle

The book by Mikhail Kelmovich, Joseph Brodsky's cousin, fully justifies its title "Metaphysics and Everyday Life", highlighting the title character in two dimensions. On the one hand, as an outstanding thinker who was visited by transcendental revelations, and on the other hand, as a man who was no stranger to anything mundane, a "very red—haired guy" whom the author of the book, by right of close kinship, often calls simply Axes. Critic Lidia Maslova presents the book of the week, especially for Izvestia.

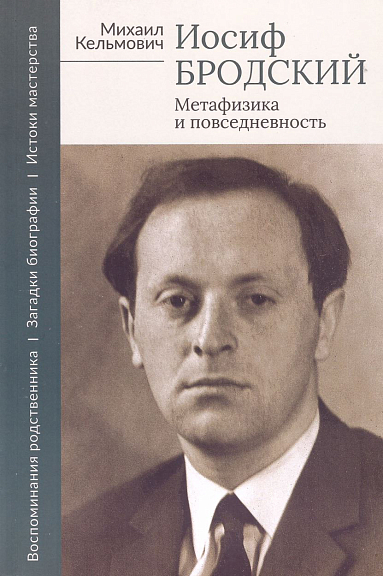

Mikhail Kelmovich

"Joseph Brodsky: Metaphysics and Everyday Life"

St. Petersburg : Descripta Publishing House, 2025, 224 p.

Kelmovich describes in detail why young Brodsky's reckless and "sloppy" behavior by Soviet (and, in general, by any) social standards often aroused not so much respect for his family and friends as fears for his future fate: "Few people know what Joseph was like when he was just starting adulthood. And how his parents and relatives felt about the fact that he dropped out of school, and about his subsequent risky adventures." According to Kelmovich's descriptions, it is quite possible to understand the relatives of the troubled teenager Osi, who dropped out of school at the age of 15, who were "disturbed by the endless succession of dubious jobs, periodic loitering, a lot of strange, risky and purposeless actions, but most of all — an incredible number of completely unbearable and unreliable friends."

More precisely, Sergei Dovlatov spoke about these "searches for himself" later.: "Brodsky has created an unheard-of pattern of behavior. He did not live in a proletarian state, but in a monastery of his own spirit." A very apt description of Brodsky's flexible personality belongs to his friend Natasha Sharymova.: "Brodsky rarely spent a whole evening in one house. He usually managed to visit several companies. He was bored talking to the same people, especially if they couldn't get off the ground and soar to poetic or philosophical heights. Joseph was worried that there were more interesting conversations going on somewhere at this moment. He let people through him like a whale passes through plankton in search of valuable food."

Perhaps this dangerous and marginal slob, eater of human plankton, turned out to be more lively and interesting in the book than another, sublime hypostasis of Brodsky — a spiritual visionary who, as a result of some transcendent experience beyond the "metaphysical horizon", became a great poet. Kelmovich learned the concept of this horizon from Brodsky himself — his dictum that "the presence of a metaphysical horizon distinguishes real literature from fiction" is repeatedly repeated in the book, which is a collection of diverse materials written at different times.

The first and second parts are of a classic memoir nature — in them the author tells about numerous common relatives, his own and Brodsky's, in the third part he builds a "parallel biography" of the poet ("an attempt to assemble into a single plot little—known episodes of Joseph Brodsky's life related to the search for revelation"), and in the fourth he analyzes some poems again-again, from a metaphysical point of view. In the final short essay, metaphysics literally doubles down — it is called "Brodsky's Two Metaphysics" and explains that "in the context of the transcendent" some of the poet's works can be divided into two groups, although the difference between them is somewhat vague: "The poems of the first are based on the poet's worldview. The pseudometaphors of the second are born directly from the perception of the moment "here and now".

Quotations from Brodsky himself help to bring relative clarity. He was able to masterfully evade the answer to a stupid question, or, depending on the mood, he expressed himself very clearly and concretely, for example, that some absolutely simple things are enough for a poet for metaphysical revelation and creative insight. Brodsky's love for "vodichka" in all its manifestations is well known to his fans, and besides, Kelmovich quotes Brodsky's lyrical confession to director Elena Yakovich, who shot the documentary "Walking with Brodsky": "There are two main shows for me in the world. It's this (water) and clouds. <...> My head is spinning, and you can get into an absolutely wonderful ecstatic state." But at this moment, the serious literary critic Kelmovich severely rebukes his romantic uncle, who is daydreaming in the bosom of Venetian nature: "Let's not confuse the usual admiration for the beauties of nature with the approach of revelation, or at least with the experience of "stopping the world."

But if we ignore such attempts by a literary critic (perhaps inadvertently, subconsciously) to put Brodsky with his special perception of the world on some pretentious coteries, Kelmovich's book, like his previous memoirs "Joseph Brodsky and his Family", certainly contains a lot of interesting information, colorful human portraits, wonderful locations (such as the famous Room and a half where Brodsky lived with his parents) and curious testimonies from people who knew the Nobel laureate well.

Kelmovich does not quote Evgeny Rein's famous ironic pun on Joseph's dear friend, "a fox dressed in purple and gold," which adds a bright color to Brodsky's image, but he quotes excerpts from two interviews with Rein, which are also not devoid of wit. Answering the sacramental question of whether Anna Akhmatova was Brodsky's mentor, Rain gives a streamlined answer: "Akhmatova's influence can be traced in very important things, but drowned somewhere in the second row: in some cultural layer, in some moral respect, in the price of words, in psychology." But in the next interview, Rain openly mocks the simplicity of an obscure journalist who asks about Brodsky's mentors: "Yes, he called me his teacher. But this is a pretty difficult problem. I don't really understand what I taught him. Should I drink port wine?"

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»