Secret material: Izvestia publishes a fragment of Joseph Conrad's novel

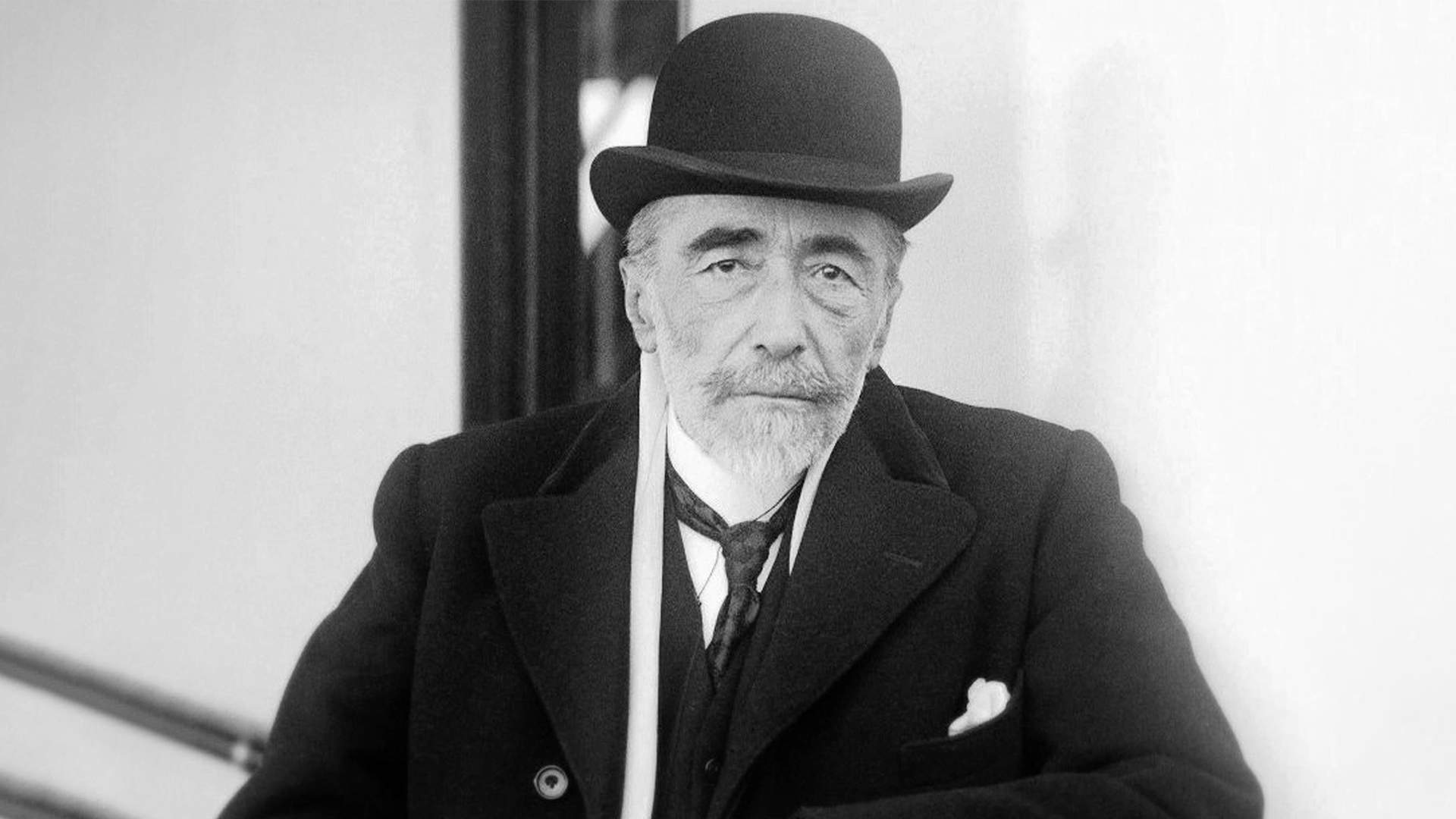

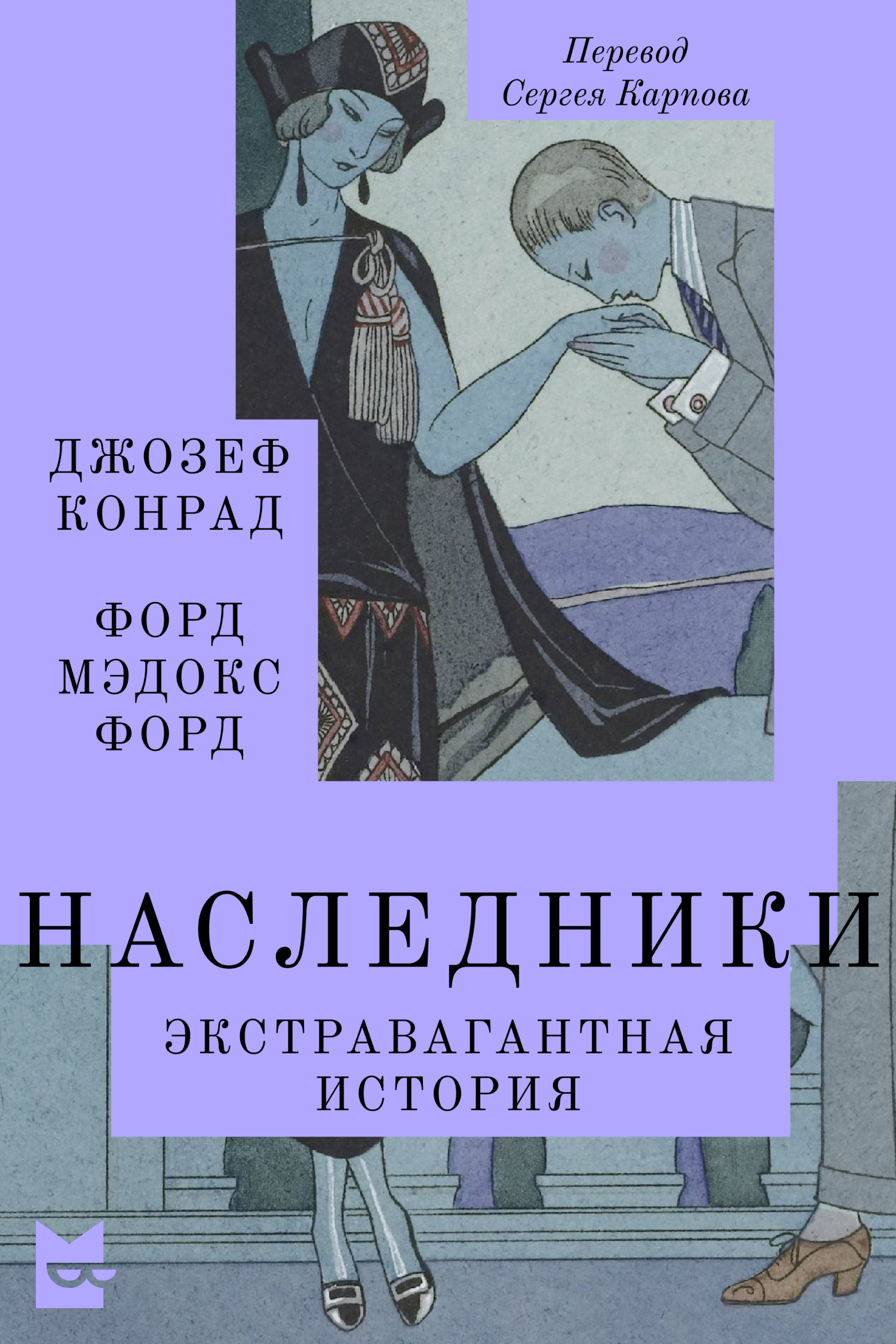

Joseph Conrad, a British man with Polish roots who was born in Berdichev and grew up in Odessa, is less known in Russia than he deserves. Not all of his books have been translated into Russian, although many of his works have long become classics in our country. First of all, "Heart of Darkness", which is especially popular also because it formed the basis of the film "Apocalypse Now". At the same time, written shortly after "Heart of Darkness" in 1901, the novel "The Heirs" has never been published in Russia, although the plot (an earthman's novel with an alien who plans to take over the Earth) and the genre mix of love, adventure, fantasy and political novels make this work at least intriguing. "The Heirs" was written jointly with Ford Herman Huffer, who is better known as Ford Madox Ford. The novel was translated into Russian by Sergey Karpov as part of the "Yandex Books Translations" series. The printed version will be released in Subscription Editions, and the audio version was voiced by actor of the Satire Theater Artemy Sokolov-Savostyanov, star of the new TV series Eterna.

Joseph Conrad, Ford Madox Ford. "The Heirs" (fragment)

—Ideas," she said. — Oh, as for the ideas…

- Yes? I ventured to ask. — As for ideas?..

We went through an old gate, and I glanced over my shoulder. The midday sun shone over the stone facade, small statues of saints, stucco canopies, dried mud and white streaks of bird droppings.

—Here," I pointed, "doesn't that mean anything to you?"

She shook her head in both denial and disdain.

"But," I muttered, "associations... ideas... historical ideas."…

She said nothing.

—That's how it is with you Americans,— I began, but her smile stopped me.

She seemed to be grinning at the words of an elderly lady who was outraged by the behavior of her modern daughters. It was the smile of a man confident in his undeniable superiority.

In conversations of any length, one side always has an advantage over the other—hierarchical, intellectual, or social. In this conversation, my companion, if she did not possess an unspoken superiority of will, at least claimed it, did not doubt it. I'm not used to this. I loved to talk and was proud of my loose tongue.

I had already cast glances at her; but now, squinting, I looked at her in a new way, assessing her. I got distracted from my usual gloominess, wondering what kind of person she was. Lush hair, beautiful eyes, and a fair amount of charm. Yes, all this is true. But there was something else, too-something... not related to beauty. His facial features were so perfect and graceful that they seemed fragile, almost transparent, but there was no hint of vulnerability; there was incredible strength in his gaze. Her hair is blond with a tint, and her cheeks are rosy, as if a warm light is falling on them from somewhere. She looked quite familiar, until suddenly you catch yourself thinking how unusual she is.

"Where are you going?" "What is it?" she asked.

— I'm going towards the Louvre.

"May I come with you?"

I looked at her, thinking to figure it out at a glance. Of course, it was impossible. "There will be more time to puzzle," I thought.

"The roads are open to everyone,— I said. "So you're not American?"

She shook her head. No. But she's not an Australian, and she's not from any of the British colonies.

"You're not English,— I reasoned. "You speak too well."

I was annoyed. She still didn't answer. She smiled again, and that's when I got angry. In the church, she smiled the same way when she heard a minister praising particularly disgusting examples of restoration, and it was this smile that gave me the courage to approach her to respectfully support her opinion and criticize the plaster molding.

You know how they address a young lady who can obviously stand up for herself. That's how I talked to her. She smiled at the guide's chatter as he showed our enthusiastic tour group the place where Blessed Thomas was martyred, and there was a sense of superiority in that smile. It had attracted me at the time, but now that she was smiling the same way, looking past me—not really at me—on the crooked roads of the town, I couldn't hide my irritation. After all, I'm not anyone; I'm not her church minister. In those days, I thought a lot about myself, and during the time of loneliness and long reflection, a lot of self-conceit crystallized into a habit. I was a writer with high—lofty—ideals. I withdrew from the world, led a reclusive life away from cities, as hermits should, in the hope that one day I would achieve something — I would put something great on paper. Suddenly she read my mind.

"You're writing," she said confidently.

I asked her how she knew if she'd read anything of mine, even though there wasn't much to read.

— Are you a famous author? "What is it?" she asked.

— Alas, no! I replied. "You know that yourself.

— Would you like to become?

"All writers want to," I replied, —although some people object that we strive for high things.

"I understand,— she replied thoughtfully.

I had a feeling that she was making some kind of decision about me. With an innate aversion to such an attitude, I interrupted my unknown thoughts.

—But come on,— I said. — It's not interesting to talk about me. Let's talk about you. Where are you from?

And again it occurred to me that I was completely unfamiliar with this type. It's still the same smile—as far as I've seen, it's exactly the same. Smiles also have their own subtle nuances, like laughter and intonation. I couldn't resist talking again.

"Where are you from?" I repeated. — You must be from some new country. I'll swear you're a foreigner if you look down on us. You're so good at getting on my nerves that I'll take you for a Prussian. But it is obvious that you are from a new country that has just started to look for yourself.

—Oh, we'll inherit the earth, if that's what you mean," she replied.

"There are different ways to understand this,— I said, trying not to let her piss me off. "Where are you from?"

I knew perfectly well that one question was enough, but I probably continued in an attempt to show my intellectual superiority.:

— You know, let's play fair. I'm ready to tell you something about myself - I've already said the main thing. Reciprocate and you will, it will be fair.

— Why do you have to play fair? "What is it?" she asked.

"What do you have against it?" Or do you not consider honesty to be a national trait of your country?

"Are you really that curious about where I'm from?"

I casually confirmed it.

—Listen," she said, and made a few sounds.

A strange, unnatural feeling came over me. It came suddenly, like a sudden gust of wind on a windless day.

—What... what is this?" I exclaimed.

—I said that I live in the Fourth Dimension.

I regained my composure, deciding that I had simply sensed some unknown and unimportant physical phenomenon.

"We must be climbing too fast,— I said. "I don't feel well." I didn't hear what you said.

I'm definitely out of breath.

—I said that I live in the Fourth Dimension," she repeated with surprising seriousness.

—Oh, come on,— I protested. — What a game. Bring a newly recovered person to exhaustion, and then torment them with riddles.

I regained my breath and the desire to rant. But for now, I just looked at her. I was beginning to understand. It is quite obvious that she is a foreigner in a foreign country, in a country where her national characteristics are more pronounced. She must be not an American, but of another race, incomprehensible — Semitic or Slavic. I've never seen a Circassian in my life, and it used to be assumed that Circassians were fair—skinned beauties and the like. And everything that was repulsive about this girl was explained only by the difference in mentality. After all, we're not that different from horses. We are afraid of what we do not understand, even consider ominous. And she seemed sinister to me.

"You still won't tell me who you are?" - I asked.

"I've already answered."

— If you think that I will believe that you live in mathematical nonsense, then you are mistaken. And seriously.

She turned and pointed at the city.

— Look at this! — She said.

We've already climbed over the western hill. At our feet, under a sky from which the wind had blown away all the clouds, a valley spread out—a wide and shallow cauldron, suffused with purple smoke from chimneys. And the golden church tower soared above the red roofs. A picturesque painting, the last and greatest word in art. I shifted my gaze to the girl. I was touched, and I knew that this greatness in front of us couldn't help but touch her, too.

She was smiling.

— Look at this! — She repeated.

And I looked.

All the same purple and red, and the golden tower, painting, the last word. She said something, a sound.

What happened? I don't know. Everything looked vile. It was as if I saw something outside, something bigger-bigger than cathedrals, bigger than the very idea of the gods to whom the cathedrals were dedicated. The tower was skewed. I looked beyond it and saw not roofs, not smoke, not hills, but the unembodied, unembodied infinity of space.

Everything passed in a moment. The tower resumed its rightful place, and I stared at my companion.

"What the hell!" I exclaimed in a panic. "Why the hell are you playing tricks on me?"

"As you can see," she replied, "you still have the rudiments of perception.

"I'm sorry if I don't understand," I said, clutching at the shards of pride. — I'm a hot-tempered person.

I wanted to hide this sudden nakedness of mine.

"I'm sorry for the harsh language," I added to prove that I had regained my composure.

We continued walking in silence. I was shocked, physically and mentally, and I tried to hide the cause of this condition from myself. After a while I said:

— So you want to keep... your incognito.

—Oh, I'm not making a mystery out of myself," she replied.

"You just said that you come from the Fourth Dimension,— I remarked ironically.

"I really come from the Fourth Dimension,— she said patiently.

She spoke in the tone of a person in difficulty, but aware of this difficulty and ready to overcome it. She felt the exhaustion of a literate adult, forced to explain to stupid children — over and over again — something elementary from the multiplication table.

She accurately read my thoughts, guessed the exact wording. She even prefaced her next speech with the word "yes."

—Yes,— she began. — It's like I'm trying to explain the ideas of the new century to a person from the previous century. She paused, searching for a suitable example that I would understand. — It's like I'm explaining to Dr. Johnson the techniques and popularity of the Cockney poetry school.

"I realized," I said, "that you don't put me above the Choctaw. But what I don't understand is what does this have to do with... what did you say, the Fourth Dimension?

"I'll explain,— she replied.

—But please explain it like a Choctaw,— I said kindly. — Clearly and convincingly.

— Absolutely.

And the girl began a long speech; I am giving it in abbreviated form. I don't remember the exact words—there were too many of them; but she spoke as if written. Her choice of words, her expressionless voice were mesmerizing. It was like listening to a phonograph recording a technical text. I was attracted by an admixture of absurdity, madness; the usual sloping landscape, a straight white road that, when viewed from a height, ran away for miles and miles — everything is straight and straight, so white. In the vast blue of the sky, the singing of countless larks could be heard. And I was listening to a parody of a scientific work performed by a phonograph.

I heard about the Fourth Dimension; I learned that it was an inhabited plane of existence, invisible to our eye, but omnipresent; I heard that I had just seen it when Harry's bell tower tilted in front of my eyes. I heard a description of its inhabitants: a visionary people, extremely practical, incredible; without any ideals, prejudices and regrets; without a sense of beauty and without respect for life; free from all ethical traditions; these creatures do not know pain, weakness, suffering and death, being invulnerable and immortal. However, she did not say that they were immortal.

"You'd hate us, and you'd hate us again,— she finished.

And it was as if only then did I come to my senses. I was so caught up in the power of her imagination that I was convinced I was hearing the truth. Apparently, she was having fun like that; it's inconceivable that she wanted to scare me. I'm not going to pretend that I didn't lose my temper at all, but I replied amiably anyway.:

"Well, you've clearly portrayed these creatures as hateful.

"I'm not making this up," she said with a faint smile and continued her fun. Now she was talking about their origins: "Your..." That's what she probably called the inhabitants of my country or the population of the Earth as a whole. "... Your ancestors are also my ancestors, but you left the Dimension a long time ago, as we are leaving now, and took over the Earth, as we will take over tomorrow. But diseases were waiting for you here, as they are waiting for us: beliefs, traditions, fears, empathy... love. Honoring ideals gave you strength and sadness; you consoled yourself with beliefs and art and forgot everything!

She spoke with calm confidence in her words, with an irresistible and indifferent persuasiveness. She was only stating the facts, not explaining what she believed. By that time, we found ourselves at a small roadside tavern. A peasant in dark clothes was sleeping on a bench in front of the door, with his head on the table.

"Put your fingers in your ears," my companion ordered.

I decided to please her.

And I saw her lips moving. The peasant shuddered and sat up, knocking over his mug with a clumsy, convulsive movement of his hand. He rubbed his eyes. We left before we heard his opinion of what had happened.

"I've seen a groom do the same to a stallion,— I said. — I know that there are words with a certain effect. But don't play dirty tricks like some kind of vaudeville devil from Faust.

"I suppose it's indecent?" She chuckled.

—Basic politeness,— I replied hotly. — The poor guy was left without beer.

"What's in it for me?" "What is it?" she asked with the air of a person patiently explaining her illustrative example.

— It means a lot to him.

"But for me?"

I said nothing. Immediately after that, she stopped her story as abruptly as she had started. It was as if she had memorized the lecture and now she had come to the end of it.

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»