True to "Underwood": Izvestia publishes a fragment of a book about a Soviet typist

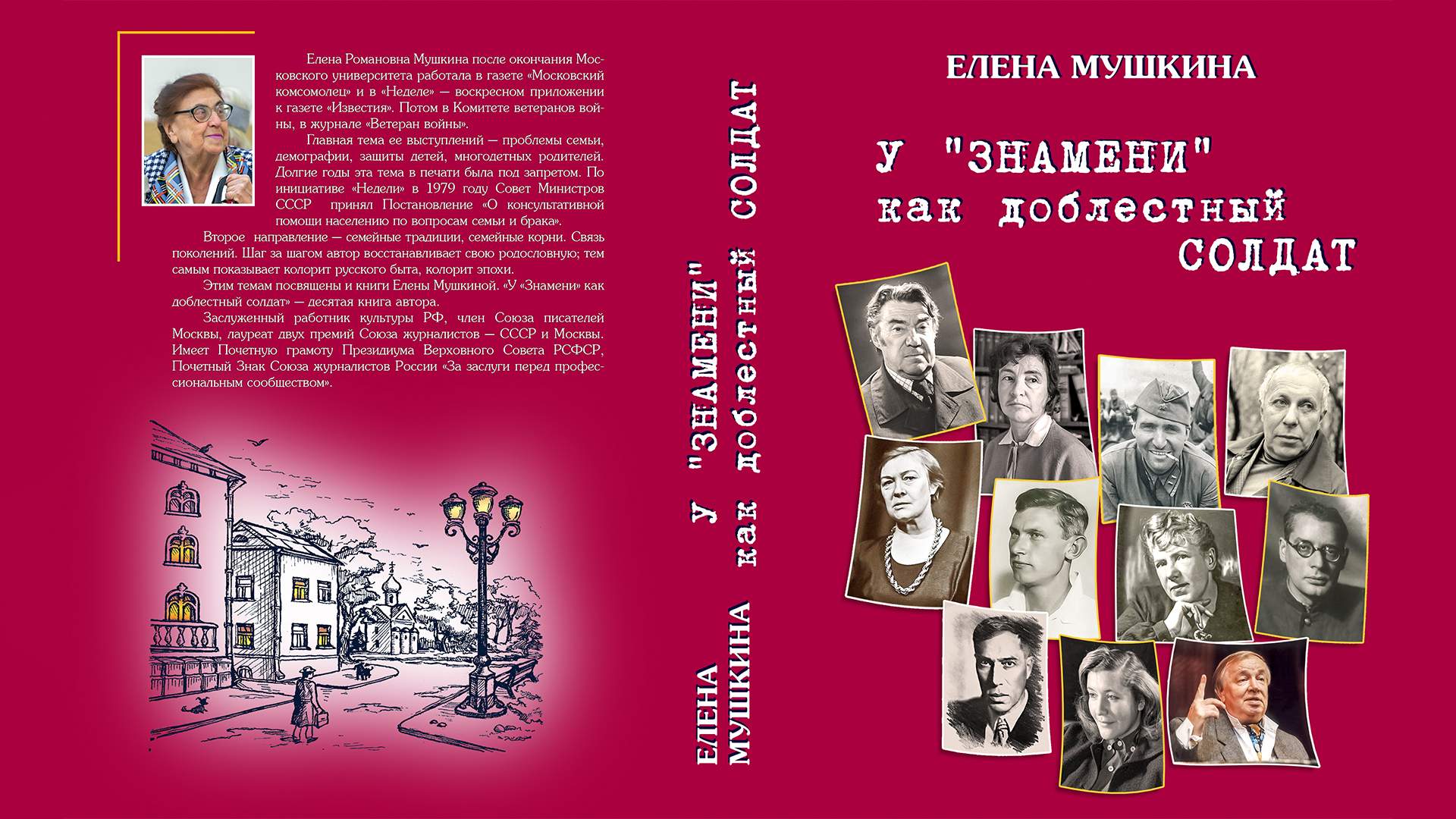

How did typists and stenographers work in Soviet times? What was the most difficult thing for them at the Nuremberg trials? And how could the history of an entire country be reflected in the life of one humble worker? This is described in Elena Mushkina's book "At the Banner as a Valiant Soldier," which will be published this year by the Northern Pilgrim publishing house. For more than 30 years, Elena Mushkina worked in the weekly supplement to Izvestia — Nedelya. And her mother, Nina Mushkina, was a typist at the Znamya magazine. The new work of the writer is dedicated to her. Izvestia publishes an excerpt from the chapter "A reporter changes his profession."

Elena Mushkina "At the Banner as a valiant soldier" (fragment)

In the 70s, the column "Reporter changes profession" appeared in journalism. After working in a new profession for a few days, the journalist began to see it as if from the inside. I loved this column, and I talked about service professions on the pages of The Week. Cook, waiter, dressmaker, telephone operator, salesman...

The call came from the publishing house "Molodaya Gvardiya", Vladimir Aleksandrovich Taborko:

— We read your articles. Interesting. We want to order a book. The series "Who to be". Add the professions of conductor and typist.

—Typists?"

— Yes, yes.

What a blessing! I dealt with the guide quickly. I took a ride with him to Tallinn. And the typist… There's no need to take an interview here. I know everything: my mother, Nina Leopoldovna Mushkina, worked as a typist for the Znamya magazine.

But Mom rebelled.:

— About me — absolutely not!

Still, I didn't write much, just a few pages.

- No! Immodest!

An arbitrator was needed. Mom rushed to Lyudmila Ivanovna Skarino, the deputy editor-in-chief of Znamya.

"But I'm leaving tomorrow." To the Baltic States, to Dubulty, to the House of Creativity. I can take the manuscript with me.

...The telegram from Dubulta arrived at the very end of September 1972. With what impatience we have been waiting for it! I don't know who was more worried, Mom or me. What is the verdict?

"It should be printed very well, I sent the manuscript in small corrections, I sent the details in a letter to Skarino."

"Well,— Mom sighed. — There's nothing to do. If Lyudmila Ivanovna thinks so…

And then the promised letter arrived from Dubulta.:

"Dear Nina Leopoldovna… So, about the case. I have carefully read the manuscript you sent, and my firm impression is that it is absolutely necessary to print it. Everything that's said about N.L. is fair and quite modest, so don't panic. I also went through the text with the wizard's hand and removed everything that was a little dubious.

It would be nice to include some philosophical paragraph stating that any great and creative work requires not only the efforts of the creator himself, but also the help of various working people. To make a novel happen, it takes the efforts of a typist, typesetter, proofreader, bookstore clerk, etc. And all these people form a single team around an important, necessary and responsible task.

In short, that everyone should respect their work, even the most modest, because it is part of the great movement of life, the development of culture, science, art, etc. Without this paragraph, the manuscript will also exist, and not bad. I'm just adding decoration, something that could further enhance the main idea of the book.

Why should the story about N.L. be abandoned? Because it is concrete and evidence-based. This is convincing, and therefore important, it gives a person a perspective on life.

I would add at least one page about the Nuremberg trials and the role of the typist to enhance this amazing piece.

Perhaps the author of the book should also write a reflection on the historical responsibility of all these humble workers, say something that sinks into everyday life, so that they can fully feel here: they are doing a great thing. In a word, I bless you! Kiss. Your L. Skarino.

R. S. At the same time, I am sending the manuscript in a separate envelope."

There were few corrections or comments. She began to follow them carefully. First, they are essentially. Secondly, she understood that her mother would make sure that not a single instruction from Lyudmila Ivanovna was ignored.

First of all, let's add about the Nuremberg trials. I searched through mountains of books and articles: about war criminals, about the public prosecutor… Nothing about typists! But they were there, both typists and stenographers. Where to look?!

"At home in Izvestia," Mom laughs. — Tamara Nosova, head of the mashburo. Say hi. We worked with her at Zhurgaz.

Of course, Tamara Vladimirovna perfectly remembered how her luggage, sent to Nuremberg, carried an old Underwood, which had served faithfully for many years. A hard worker of super retirement age.

Tamara Vladimirovna told me in detail about her work in Nuremberg. Then I wrote about it on the pages of Izvestia:

"A special room, the so-called press room, has been set up for journalists in the Palace of Justice. The press room. Everyone could put a typewriter on the table and tap out their message. And we helped those who couldn't type. However, there weren't many of them.

But our main task is more important and difficult — the transcript of the meetings. All the stenographers and typists were parliamentary. This means that the decryption took place immediately, from the wheels. The stenographers worked with headphones on because they recorded not the speeches, but the translation into Russian. Synchronous. Usually, there was a crackle in the headphones, and the noise in the hall got in the way. They'll sign up and come straight to us. We were ready: the paper and carbon paper were inserted into the carriage of the machine. Use your fingers on the keyboard so that you don't waste a moment.

The typists' room is not far from the meeting room. The windows overlooked the prison... and this prison, and the creepy text that was dictated to us about fascist dungeons, about torture, and the very appearance of the criminals — we had a pass, and when we were free, we could attend meetings — all this made a depressing impression. Well, the translators, who had to voice the words of speech, were simply in a state of shock.

Naturally, the translators in Nuremberg were highly qualified. Still, misfires happened. When Goering testified, the words "Trojan Horse politics" were heard. And the young translator "stalled": A Trojan horse… Is it a breed like that? The confusion was short-lived: an experienced colleague who knew ancient history well came to the rescue.

The work required tremendous effort and concentration. Complex terminology — military, legal… Names of witnesses, accusers, defenders. And the breakneck speed: fifty to seventy pages per shift."

The next morning, reports from the meetings will be in all the central newspapers. But that's tomorrow.… And they, the typists seconded to Nuremberg, know everything already today. The witnesses, moreover, the participants of the events!

I don't remember when Tamara Vladimirovna retired. But I remember very well that she was typing on an old Underwood. The Izvestia machine shop has long since updated its production tools, and everyone has already been working on electric machines. And only she remained faithful to her "Underwood".

Naturally, the typists in Nuremberg were not the main ones. Special correspondents of the central newspapers went there. Of course, and from Izvestia. The most qualified, the most worthy. The trial lasted almost a year, from November 20, 1945 to October 1, 1946. Horrific facts of atrocities and crimes were made public in the "Hall 600" of the Palace of Justice. Many years later, in March 2017, my colleague Stanislav Viktorovich Sergeev told about this on the pages of Izvestia.:

«...Many years later, I happened to visit Nuremberg. I went into the courthouse, which now houses the historical museum. It was a weekday. There was not a soul in the relatively small room, decorated in heavy dark brown tones. There were benches for the defendants to the left of the judges' table. I carefully sat down in the far right seat in the first row. A little later, in the museum exhibition, I looked at the famous photo: It was Goering's place, the second man in Hitler's hierarchy. It got creepy..."

The same panorama of the dock, but with real characters on them, was captured by Izvestia's special correspondent, the famous documentary filmmaker Roman Carmen, with his camera. This is his picture, published in the newspaper on November 24, 1945, which opened the Izvestia photo session from the Nuremberg trials. Soon, another representative of Izvestia at the trial, the legendary cartoonist Boris Yefimov, used the same angle in a ruthless political cartoon...

Mikhail Dolgopolov was also sent to Nuremberg to work on the trial on literally two fronts: he represented both Izvestia and the Soviet Information Bureau there. In 1960, we young people listened with our mouths open to the stories of the "newspaper wolf" Dolgopolov, at that time a cultural columnist for the newspaper, who knew the whole of Moscow and whom the whole of Moscow knew.

In Nuremberg, Mikhail Dolgopolov stood out among the journalistic fraternity for his style, bearing, and manners, and even here he sometimes noticed details characteristic of a journalist who wrote on cultural topics in his peaceful life. In one of his reports, the following phrase flashed: "The clothes of our female staff... it looks so poor that the British and Americans laugh." Yes, our "female staff" who survived the hardships of the war — typists, stenographers, translators — looked modest and inconspicuous, but their main advantage in their work was professionalism and courage..."

This article by Stanislav Viktorovich was published in Izvestia after the death of the typist Tamara Vladimirovna. I think, after reading about the clothes, she would have sighed and spread her hands. Unfortunately, there were few fashionable clothes in the Soviet Union in the post-war 1945.

And also about Tamara Vladimirovna and Nuremberg. In 2024, the Moscow Union of Journalists received a letter (I quote in the original):

"To the First Secretary of the Russian Academy of Sciences

Hi!

I am writing to you to find out about the female reporters from the USSR at the Nuremberg trials in 1945-1946. This is part of the Nuremberg Women's study, and it's important for me to make sure that women from the Soviet Union are properly represented.

I found several names of women in this category.:

Volchansky (Sergeev) N.S., who wrote for Novoe Vremya

Bobrava Tatiana G.

Bryukhanskaya Ida A.

Gorbovskaya Olga V.

Nosova Tamara V.

— I found information that she worked at Izvestia as a typist and interviewed Elena Mushkina on this topic. Is she still alive? However, I can't find much information about them. I would appreciate any help in getting more information.…

With great gratitude,

Dr. Jonathan Cummings"

***

So, I added about the Nuremberg trials. But Mom doesn't calm down.:

— Have you forgotten that Lyudmila Ivanovna also asked me to write about the "everyday routine", about how important the work of these humble typist workers is?

So I went to the typewriting bureau on Trubnaya Street.

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»