Light under blackness: what the patriarch of conceptualism recalls

The founder of Moscow conceptualism, social art and one of the most expensive contemporary artists, 91-year-old Eric Bulatov recorded his memories on a dictaphone to pass the time in the hospital, where he was admitted last year. In the resulting book, Bulatov talks about his life in a very simple and unsophisticated language, as minimalistic as many of his artistic solutions. Nevertheless, these memoir sketches reflect the complexity and originality of Bulatov's vision, a view not only of the objects, landscapes or people depicted, but also of the universe as a whole. Critic Lidia Maslova presents the book of the week specifically for Izvestia.

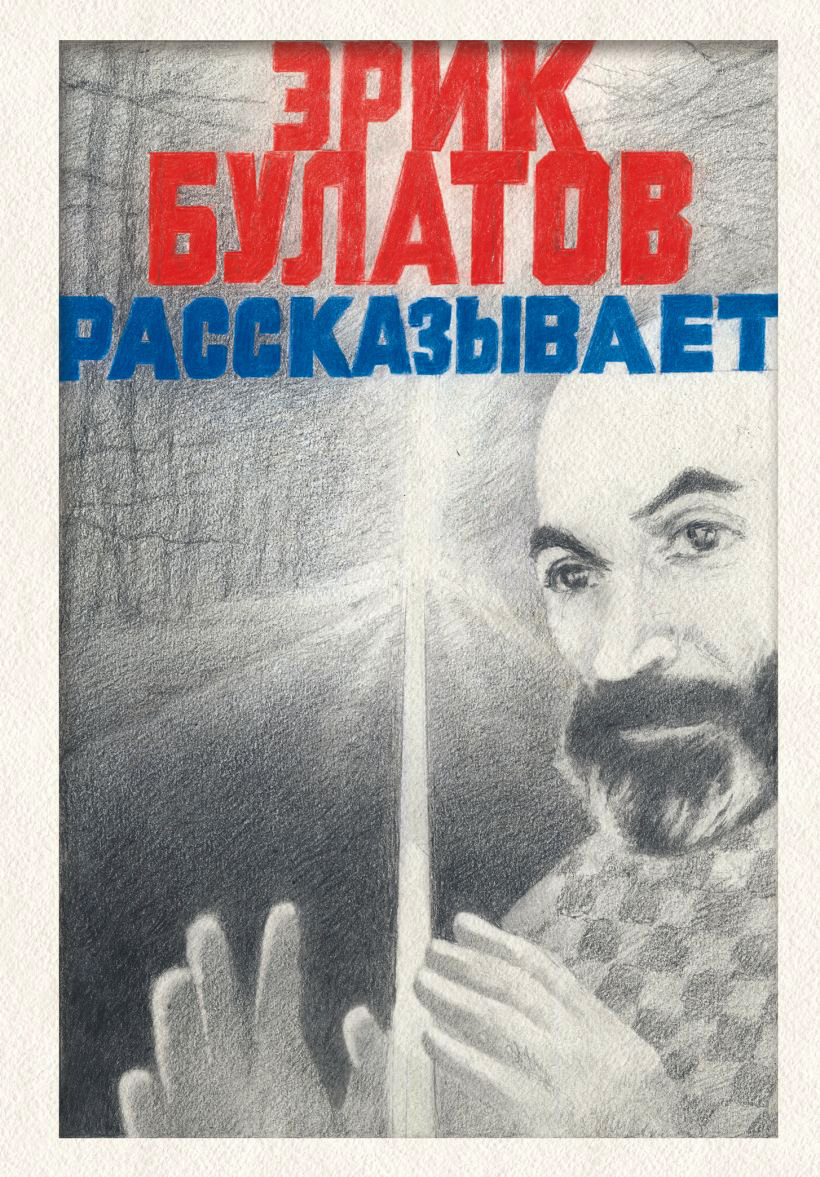

Eric Bulatov

"Eric Bulatov tells the story"

Moscow: Eksmo, 2025. — 272 p.

The creative, professional component of the biography (or, as the author himself puts it, "work problems") in Bulatov's book rather prevails over the personal, although it is impossible to clearly distinguish them. Moreover, little Eric, who owes his unusual name to the hero of August Strindberg's drama "Eric XIV" (the production with Mikhail Chekhov made an indelible impression on the child's parents), groped his future professional path early and rushed along it without any special obstacles, receiving the blessing of his father, who was delighted with his son's first drawings: "Of course, in many children draw well at that age, and it hardly meant anything serious, but the father was delighted and decided that his son should become an artist." Even the fence of the gorgeous summer cottage of the first Stalin Prize winner, artist Pavel Kuznetsov, did not become an obstacle, to which the enterprising Eric climbed to show his drawings — this is one of the most striking episodes of the childhood period.

Bulatov received his first drawing lessons at the age of six from a neighbor in a country village and tried to illustrate an episode from Ruslan and Lyudmila by reproducing a drawing from a book: "I tried to draw better than it was in the book." At that time, Eric could not have imagined that for a long time he would have to earn money, like many of his Soviet colleagues, by illustrating children's books — together with his best friend Oleg Vasiliev, a classmate at the Surikov Art Institute. Bulatov's first commercial success is also connected with Vasiliev: even in the third year, friends bring their sketches to the salon on Gorky Street, and on the very first day the drawings are sold for what seems to poor students to be a lot of money.

And finally, in the company of Vasiliev, Bulatov comes "in despair and confusion" to Vladimir Favorsky, whom he considers one of his teachers.: "We were then graduating from the Surikov Institute and clearly understood only that we had been taught the wrong way. And all our skills and knowledge are worthless, and there is a real great art, but it is sealed from us, and we don't even vaguely know how to approach it. We knew that there were living priests of this sacred art. There were three of them — Falk, Favorsky, Fonvizin. And we went to them and asked. We just had nowhere to go."

The story of the "three F's" is the semantic center of gravity of Bulatov's book, to whom Favorsky opened his eyes to the opportunity not only to feel, but also to understand art. It was from Favorsky that Bulatov learned one of the basic concepts of his artistic philosophy — space: "It turned out that the nature of the painting is twofold. On the one hand, it is an object that exists in a number of other objects, as well as a chair, table, shelf, and as such can hang on the wall and be part of a room interior. A painting is an object that has an edge (or frame), a surface on which paint can be applied. This is, so to speak, the material part of the painting. <...> But at the same time the painting is a space. Like any quadrangle of a bounded surface, it has a center, a periphery, and an edge with energy of varying nature and quantity."

Bulatov identifies three stages in the perception of art: understanding art as a whole, understanding one's place in this whole, and understanding one's professional responsibility. Speaking about the latter in relation to an artist who is inevitably forced to touch on good or evil in every work, Bulatov cites a dispute between the "metaphysician" Favorsky and the "dialectician" Falk, whose position is clearly close and sympathetic to him: "Falk deeply believed in his harmony and felt it as alive and authentic. That is, he realized that this harmony is not a product of his artistic arbitrariness, whim or taste, but is contained in the world around him, and he, the artist, only extracts it from there, makes it explicit. <...> He refuses to dissect this harmony in order to find out how much it consists of good and how much of evil".

In the last quarter of the book, Bulatov moves from philosophical arguments and "work problems" to more intimate memories and tells the story of his third (successful, unlike the previous two) marriage to Natalia Godzina. But even here, the personal is closely intertwined with the "worker" — with the analysis of the painting "Natasha", where the girl the artist is in love with is depicted against the background of a snow-covered monument to Lenin in a country village: "Natasha was upset at first that the portrait turned out to be against Lenin's background. And the point was that a living human figure was placed in the foreground, and behind it there were some ghosts, trees, and fog. Natasha's figure is the only absolute reality that stands up to the illusory world." Emphasizing the important role of "Natasha" in his evolution as an artist, Bulatov indulges in a detailed analysis of the painting, including from the point of view of the most important conceptual concept for him — light: "... for all the social workload of the painting, it is filled with pinkish frosty light. And the light is, firstly, a personal, lyrical presence, and secondly, from the outside, of course, one can think that this is the light of hope. It is as if all nature opposes the absurdity of a dead phrase, as if Lenin were alive forever."

Along with space, light acts as the cornerstone of Bulatov's aesthetics, constantly appearing in his arguments on various occasions and in different aspects. "Light is my faith. I believe that no matter how dark it is, there is still light at the core, and if you illuminate some fragment of darkness, then there will be the same normal life. That is, there is always light under the blackness. And I mean my own light, not illumination from somewhere outside, by the sun or a lamp, for example. Black has its own light too, coming out from under black. Light in general is at the heart of the entire universe, as I understand it, as I believe, the light is internal," Bulatov's reasoning translates the theme of light from a purely artistic plane to a philosophical and religious one.

However, the word "plane" is highly inappropriate when applied to a conceptualist who has always sought in various cunning ways to pull the viewer inside the painting, reveal its "inexhaustible spatial possibilities", expand the boundaries of its perception.: "To enter the depicted world, to be a direct observer and an "accomplice" of the events presented by the artist is the greatest happiness for the viewer, who, having forgotten about his real existence at the moment of contact with the artwork, finds himself in another space."

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»