Reception day: when the world's first radio signal was transmitted

On May 7, 1895, Russian scientist Alexander Popov demonstrated to his colleagues his invention, the world's first radio receiver. Today, on this day, we remember the great inventor. Details can be found in the Izvestia article.

From the Urals to Kronstadt

The inventor was born into the family of a priest, and spent his childhood in the Ural village of Zavodskoy. At first, Popov followed in his father's footsteps and entered a theological college, but he was most interested in physics. Soon he passed the exams for the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics at St. Petersburg University. One of his teachers was the great Dmitry Mendeleev, who became for Popov a model of a researcher and experimenter for whom nothing is impossible. There he became familiar with Bell's telegraphic devices and telephone and became fascinated by the idea of wireless signal transmission.

The young scientist was inspired by the work of British physicist James Maxwell, who predicted the existence of electromagnetic waves. Popov undertook not only to prove their existence, but also to give them practical application. At that time, many scientists were interested in electricity, studied its mysteries, and invented new techniques, mostly lighting. But from a young age, Popov fell ill with the idea of transmitting information over a distance without the help of wires.

In 1889, Popov read an inspired report at a meeting of the Russian Physico-Chemical Society, in which he said that electromagnetic waves make it possible to transmit signals over long distances without wires. Then it was perceived as fiction. But Popov quickly moved from theory to practice.

In 1890, Popov began teaching physics at the Kronstadt Naval Technical College. By the way, there he manufactured the first stationary X-ray machine in Russia. And he was working on his main invention.

Continuing his experiments, Popov discovered that the radio receiver was capable of receiving electromagnetic radiation from lightning discharges. This discovery led the scientist to create the first radiometeorological device, a lightning detector. By 1895, Popov had constructed the world's first radio receiver. And I showed it to my colleagues almost immediately.

Lecture with demonstration

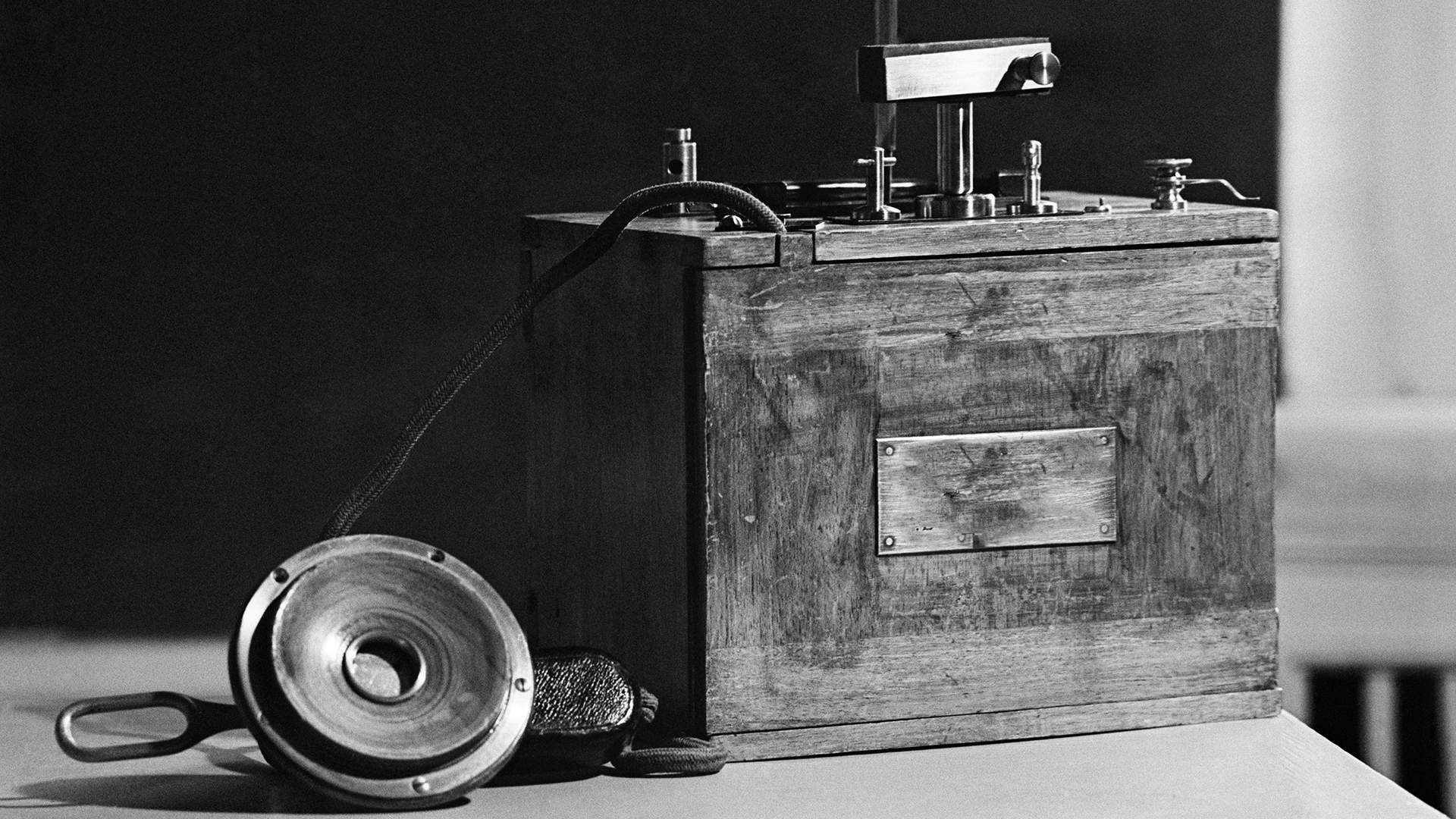

On May 7, 1895, the 36-year-old scientist delivered a lecture at a meeting of the Russian Physico-Chemical Society in St. Petersburg, "On the relation of metal powders to electrical vibrations," where he demonstrated his invention. Popov himself called him by different names. For example, "a device for indicating rapid fluctuations in atmospheric electricity." The effect was achieved due to the high sensitivity of metal powders to the slightest electrical fluctuations, which made it possible to transmit signals wirelessly. The invention made a strong impression on the audience, although not everyone understood the historical significance of this technical innovation. He talked about the lightning detector and his other ideas.

The first experiments (they were conducted in the same place, in the laboratory) made it possible to emit radio signals at 60 m. This day is considered the beginning of a new era — the era of radio. But Popov did not stop at one experiment. A year later, he transmitted the world's first radiogram — at 250 m, connecting his device with a telegraph. He used Morse code to transmit information. It was another experiment of global importance. "Despite the considerable distance and stone walls located in the path of the propagation of electric rays, at every signal that activated the vibrator, the device's bell sounded loudly," said Vladimir Skobeltsyn, a physics professor who participated in these experiments.

Two years later, Popov's device could already receive signals at a distance of 11 km, and later at 20 km. Skeptics, who initially treated his invention only as a fun laboratory experiment, became convinced of the enormous technical prospects of the invention. Popov had like-minded people, students who helped him improve his equipment. These are radio engineer Peter Rybkin, Russia's first naval electrician Evgeny Tveritinov, and Dmitry Troitsky, head of the Kronstadt Telegraph office. They can all be called pioneers of radio.

Popov was not too eager for fame, did not make a secret of his research, and published a lot openly. A few months after Popov's experiments, Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi received a patent for a similar setup. His undisputed merit is the construction of the first stationary radio station on the Isle of Wight in the English Channel. He relied heavily on Popov's inventions. Although in the scientific world it is believed that they came to similar results almost simultaneously.

Radio saves sailors

In 1900, wireless communication began to be used in the navy. The battleship General Admiral Apraksin ran aground in the Gulf of Finland. There was no communication with the crew. The icebreaker Ermak went to the rescue of the battleship. To save the ship, under Popov's leadership, sailors and scientists installed two of Russia's first radio stations: one on the island of Gogland, the other on the island of Kutsalo. The distance between them was 45 km. Popov sent radio messages to the battleship, which helped the sailors navigate. Along the way, his invention was used for other purposes. On February 6, 1900, "To the Commander of the Ermak." An ice floe with fishermen broke off near Lavensaari. Give me some help." It was the world's first radio-transmitted distress call.

Admiral Stepan Makarov was one of the few who immediately appreciated the importance of this invention, which he called a "major scientific victory" in a telegram to Popov. On April 14, 1900, the battleship was saved. By that time, Popov had sent several dozen radio messages there, and Admiral Makarov had succeeded in obtaining a government decision on the introduction of wireless telegraphy on ships of the navy. In a few years, the researcher has created about 50 shipboard radio stations. Russian Russian engineers were unfortunately viewed with distrust by officials. Before the Russo-Japanese War, they signed an agreement with a French company that brought down the Russian fleet. But Popov and Makarov fought for the priorities of the domestic manufacturer to the last. These ordeals shortened the life of the inventor, who lived only 46 years.

This is Moscow speaking!

Real radio broadcasts — news releases, music broadcasts — began in our country in 1919 at the Nizhny Novgorod Radio Laboratory. Very soon, despite the Civil War, experimental radio stations began to appear in all major cities of the country. In Moscow, under the leadership of engineer Vladimir Shukhov, a radio tower was being built, which made it possible to expand broadcasting from the capital. By the way, the famous Eiffel Tower in Paris, built for no particular practical purpose, was used for radio stations at that time. Radio conquered the world and united nations. The whole world has heard two words: "Moscow speaks!"

It is possible to talk endlessly about the role that radio has played in the history of the last 130 years. Street loudspeakers became a sign of the 1930s and 1940s, by which people used the radio to learn the most important news. This was the case, for example, on June 22, 1941. The voice of announcer Yuri Levitan, who became the "voice of the Great Patriotic War" for millions of people and a "personal enemy" for Adolf Hitler, will forever remain in the national memory. And in besieged Leningrad, radio helped hundreds of thousands of people who suffered from hunger and disease to survive.

The historian Vladimir Mavrodin, who also spoke to the Leningraders, very accurately called radio the "thread of life." The "plate" working in the apartment created the effect of an interlocutor — and, according to psychologists, it saved from nervous breakdowns, gave strength. Writers such as Vsevolod Vishnevsky, Olga Bergholts, and Nikolai Tikhonov performed every day on Leningrad radio during the war. When the voices of the announcers and writers fell silent, the measured beat of the metronome sounded on the air. It also helped lonely and sick people to feel that they were not abandoned, that the pulse of the city was beating. And people cried with happiness, and danced around the loudspeakers, and threw flowers at the disabled and the military in all cities of the country. At that time, only radio could unite and rally the people in this way. On May 9, the whole country learned about the Victory on the radio. On June 24, 1945, a live radio broadcast of the Victory Day Parade on Red Square took place.

Radio Day became a holiday in 1945 on the eve of Victory. At that time, the 50th anniversary of Alexander Popov's discovery was widely celebrated in the country. This date was not lost even in those triumphant days, when the most important news from Berlin and Prague came every day... The decree of the Council of People's Commissars noted that his invention influenced not only science and culture, but also helped the Red Army to break the enemy's resistance. The resolution referred to "the popularization of the achievements of Russian science and technology in the field of radio and the promotion of amateur radio among the general population." On the same day, the USSR Academy of Sciences established the A.S. Popov Gold Medal for achievements in the development of methods and means of radio electronics. This award exists in our time.

Today, we cannot imagine life without satellite communications, the Internet, and navigation systems — space, sea, and highway. After all, all this is, to one degree or another, wireless data transmission. All this is the development of Popov's inventions, the first maestro of radar communications. And this story began 130 years ago in St. Petersburg.

The author is the deputy editor—in-chief of the magazine "Historian"

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»