Doomsday Night: Izvestia publishes a fragment of the novel "The Wind Knows My Name"

Salvador Allende's niece is how Isabel Allende entered literature many years ago. Since then, the number of books sold worldwide has exceeded 65 million copies, and her writings have been translated into 35 languages. She is also known and appreciated in Russia: we have published more than 10 of her novels. The last one written so far, "The Wind Knows My Name," has been waiting for release in Russia for two years. This week, this novel, published by ABC, will appear in domestic bookstores, but for now Izvestia is publishing a fragment of it — a chilling description of Kristallnacht in 1938, because Allende in this work compares the crimes of Nazism with modern US immigration policy and comes to disappointing conclusions. We remind you that the ideology of Nazism is banned in Russia.

"The wind knows my name" (fragment)

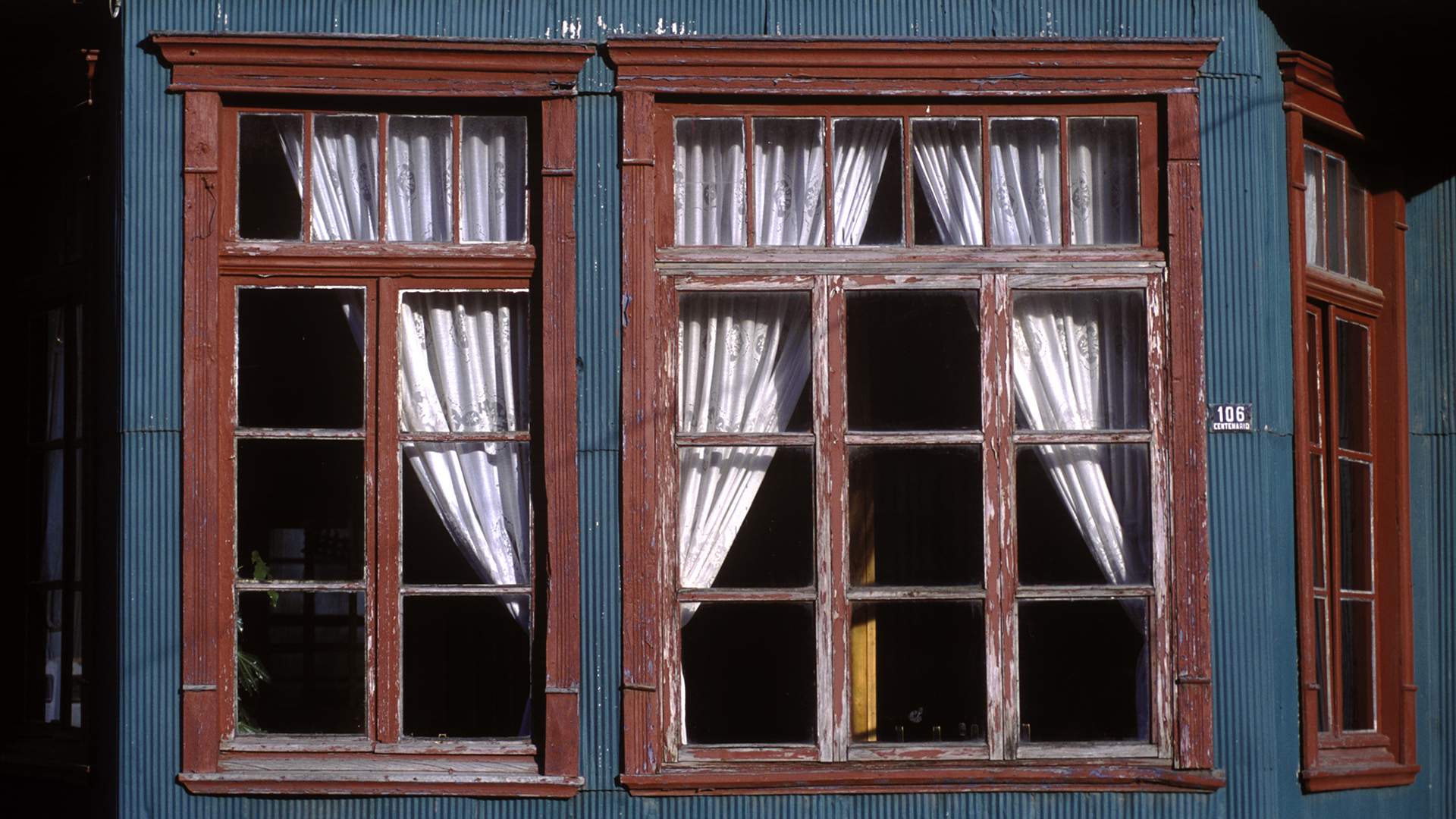

The night was filled with terror. It was only ten minutes later that Raquel Adler realized the gravity of what was happening: the curtains were drawn and the noise and screams were muffled.

She thought that the bunch of youths who had been making noise earlier had returned. To distract Samuel, she asked him to play something, but the boy seemed numb, already anticipating a tragedy, the reality of which Raquel refused to admit so far. Suddenly, something hit the window, and the glass shattered into a thousand pieces.

My first thought was to calculate how much the repair would cost them, because the glass was custom-cut. And immediately the second boulder broke another glass, the curtain came off the ledge and hung on the last fastening.

Through the hole in the window, Raquel saw a piece of purple sky, inhaled the smell of smoke and soot. Wild screams stormed into the apartment, and then she realized that something much more dangerous was going on than the antics of drunken youths. The furious murmur of the crowd was echoed by screams of panic, the sound of breaking glass did not stop for a moment.

— Rudolph! She grabbed Samuel by the arm and dragged him to the door.

The boy barely managed to grab the violin case.

The only thing separating the apartment from Rudolph's office was a wide marble staircase with wooden, bronze-decorated handrails, but Raquel did not get there. Theobald Volker, a neighbor from the third floor, a retired military man with whom she barely exchanged a few words, intercepted her in the hallway and blocked her path.

She found herself pressed against the broad chest of the old grumpy man, who was muttering something indistinctly, and she struggled and called her husband. It took more than a minute before she realized that Volker was not letting her into the ground floor, because the raiders had already broken down the carved wooden door with stained glass and burst into the lobby.

—Come with me, Frau Adler!" The neighbor barked in a voice clearly accustomed to giving commands.

"My husband is there!"

"You can't come down!" Think of your son!

And he pushed her up the stairs, toward her own apartment, where she had never been before.

Volker's apartment was the same as the Adler's, but not bright and elegant like theirs, but dark and cold: scanty furniture, only a couple of photographs on a shelf. The neighbor dragged Raquel into the kitchen by force, and Samuel, clutching his violin and as if speechless, followed. Volker opened a narrow closet door and motioned for them to hide there and sit quietly until he returned. The door closed, and Raquel and Samuel stood huddled together in total darkness. They could hear Volker moving something heavy.

"What's wrong, Mom?"

"I don't know, honey, just stand still and be quiet," Raquel whispered.

"Dad won't find us here when he gets back," Samuel said in the same serious tone.

"It won't be long. Evil people have broken into the house, but they will leave soon.

"They're Nazis, aren't they, Mom?"

- yes.

"Are all Nazis bad, Mom?"

"I don't know, son. There must be both good and bad ones.

"But there are probably more bad ones," the boy summed up.

***

Theobald Volker had already served in the army when it fell to his lot to defend the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1914. He came from a peasant family with no military traditions, but he managed to curry favor. He was about six feet tall, possessed remarkable strength, was disciplined by nature, that is, he was born for military service, but he secretly wrote poetry and dreamed how glorious it would be to live in a peaceful village, cultivate the land and keep cattle, next to the woman he had loved since adolescence. During the four years of the war, he lost everything that gave meaning to life — his only son, who died in battle at the age of 19, his adored wife, who committed suicide with grief, and his faith in his homeland: in the end, it turned out that the motherland was just an idea and a banner.

When the war ended, Volker turned 52, and he remained with the rank of colonel and with a broken heart. He no longer remembered what he was fighting for. Defeat met, tormented by the ghosts of 20 million dead. There was no place for him in the devastated Europe, where the remains of men, women, children, horses and mules rotted in mass graves. For several years he held positions unworthy of his title, sharing the miserable fate of the defeated, until age and illness forced him to retire. Since then, he lived alone, read, listened to the radio, and composed poetry. I went out once a day to buy a newspaper and everything I needed to cook a meal.

The hero's medals were still emblazoned on his old uniform, and Volker wore it on every anniversary of the armistice that marked the collapse of the empire for which the old warrior had fought for four terrible years. On a day like this, he cleaned and ironed his uniform, polished his medals and oiled his weapons; then he opened a bottle of strong vodka and methodically got drunk, cursing his loneliness. Volker was among the few residents of Vienna who did not come out to greet the German troops on the day of the annexation, because he did not identify himself with these goose-stepping people.

Taught by bitter experience, he did not believe in patriotic fervor.

In the house, the adults shunned the colonel, who did not even respond when greeted; the children were afraid of him. Everyone except Samuel. Raquel and Rudolph were busy most of the day, each at his own job, and the woman who used to clean up at the Adler's every day left at three o'clock. If Aunt Lia did not visit her nephew, the boy spent several hours alone, doing homework and studying music.

Soon Samuel discovered that when he was playing the violin or the piano, the neighbor would sneak down with his chair, sit in the hallway and listen.

Although no one asked him to, Samuel began to leave the door open. He tried to play as well as possible for a one-man audience who listened in respectful silence. They never spoke, but when they met in the house or on the street, they exchanged a slight nod, barely noticeable, so that Raquel did not guess about the unusual relationship between her son and Volker.

After locking the neighbor and the boy and closing the closet door with the kitchen table, the colonel hurriedly changed into a gray uniform with gold epaulettes and a full set of medals, put on a holster with a luger, outdated but in excellent condition, and stood in the doorway of his apartment.

Peter Steiner stayed for a few minutes, closing the pharmacy window with wooden shutters and lowering the metal curtain on the door. He put on his coat and ran out the back door, intending to catch up with his friend, but even along a narrow side street, an indignant crowd was moving, shouting threats. Peter pressed himself against the entrance door, hiding from the raiders, waiting for them to disappear around the corner. He was burly, red-faced, with a blond crew cut as stiff as stubble; his eyes were very light, as if veiled, and with the powerful arms of a weightlifter he won any competition in strength. Apart from his wife, he was not afraid of anyone, but nevertheless decided to avoid a clash with an unbridled horde of barbarians and went around, praying that Rudolf Adler would do the same. After a few minutes, the pharmacist became convinced that the crowds had flooded the entire block and he would not be able to get through to his friend's office. He didn't think for long — he joined the human mass, snatched the party standard from the hands of some young man who didn't dare protest, and rushed into the general stream, shaking the banner.

After exploring these few blocks, Peter Steiner realized the chaos that had descended into a quiet neighborhood where members of the large Jewish community traditionally lived and worked. There was not a single pane of glass left in the shop windows, bonfires were burning everywhere, where the rioters threw everything they took out of houses and offices; the synagogue, set on fire from four ends, was ablaze under the unflappable gazes of firefighters, ready to intervene only if the flames spread to neighboring buildings.

Peter saw how the rabbi was dragged by his legs, and his head, covered in blood, was pounding on the cobblestones; he saw how men were beaten; how women were stripped of clothes and pulled out strands of hair; how children were slapped in the face, and the elderly were urinated on and kicked. Onlookers egged on the attackers from some balconies, and in one window someone raised his right hand in greeting, clutching a bottle of champagne in his left, but in most mansions and apartment buildings the doors were locked and the curtains were down.

Horrified by what was happening to him, the pharmacist realized how contagious the bestial energy of the crowd was: he, too, felt a savage craving for freedom, rushed to smash, burn and scream himself hoarse — he turned into a monster. Panting, covered in sweat, with a dry mouth and goosebumps all over his body from the adrenaline rush, he hid behind a tree and squatted down, trying to catch his breath and regain his mind.

— Rudy... Rudy... He muttered louder and louder, until his friend's name brought him back to his senses.

We need to find him, save him from the furious crowd.

Peter got to his feet and moved forward: the standard and the purely Aryan appearance served him as protection.

As Steiner had feared, Adler's doctor's office was trashed, the walls were covered with obscenities and painted with party symbols, the door was broken, and all the windows were broken. Furniture, shelves, lamps, medical instruments, medicine bottles — everything is scattered on the pavement. And my friend disappeared without a trace.

Colonel Theobald Volker met the first raiders, standing with his arms crossed on the threshold of his apartment. The door was broken down less than a quarter of an hour ago, and they've already spread through the house like rats. Volker assumed that the concierge or one of the tenants had betrayed the Jews, and maybe even marked the apartments, because later, walking around the building, he saw that the attackers had broken down some doors and left some untouched. The Adler's door remained intact because it was ajar.

Half a dozen men and young men intoxicated with violence, all wearing swastika armbands— appeared on the landing, shouting insults and Nazi slogans. One of them, who seemed to be the leader, came face to face with the colonel. He was holding an iron pipe in his hands and had already raised it to strike, but was instantly stunned at the sight of a monumental elder in a uniform of bygone times: the veteran looked down at him imperiously.

"Are you Jewish?" The raider barked.

—No,— Volker replied, without raising his voice.

There were shouts of annoyance: the raiders had not found anyone in the Adler apartment. Two slightly older men went up the stairs to Volker.

— How many Jews live in the house? One of them asked.

— I can't say.

— Step aside, we will search your apartment!

"By what right?" "What is it?" the colonel asked, and his hand went to his luger holster.

Translated from Spanish by Anastasia Mirolyubova and Boris Kovalev

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»