The main thing is from the arts: porcelain of the emperors and kinoki rebels

Capitalism and schizophrenia

Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari

It's hard to believe that one of the main philosophical works of the 20th century, the two—volume book Capitalism and Schizophrenia by Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari, has been almost impossible to buy in recent years. Translations into Russian were published about 15 years ago and have long become bibliographic rarities, for which, of course, you can hunt at second-hand booksellers, but you should prepare for very merciless prices. In addition, "Anti-Oedipus" and "A Thousand Plateaus" were released by different publishers, separately, but it is better to get acquainted with them, of course, in pairs, even if these books are completely different.

"Anti-Oedipus" is primarily about society and personality; about power and the tools it uses to manifest itself in family relationships, commerce, advertising, and so on. It is also a scathing critique of Freudianism, hence the name, which hints at the notorious Oedipus complex. But it is difficult to reduce a 500-page reflection to some kind of main idea, message. In his famous preface to the American edition of Anti-Oedipus (by the way, for some reason it did not get into the new Russian version) Another thinker-guru Michel Foucault stated: "I think the best way to read Anti-Oedipus is to approach it as 'art.'"

But to an even greater extent, these words of Foucault are true for the second volume, which by its very form, which breaks up into fragments seemingly disconnected from each other, devoid of a single drama ("plateau"), illustrates the key concept of the book: the rhizome. This is the name of the underground system, where many plant roots are connected to each other and form a complex nonlinear structure. The original "Thousand Plateaus" was released in the 1970s, and created the theoretical basis for postmodernism, which declared itself in full force. Half a century later, however, this text has not lost its relevance. Let's add that "Anti-Oedipus" is presented in a new translation by S. Mukhamedzhanov, and the translator's preface devoted to the difficulties of adapting the text proves to be a valuable addition to the main material.

Kinoki: Dziga Vertov's school

Kirill Goryachok

A lot has been said about the Soviet director Dziga Vertov in recent decades and, apparently, more will be said. "The Man with the Camera" consistently tops the list of the most important documentaries in history, and Vertov's early editing works are being recreated piece by piece by professionals and returned to the screens.

When talking about Vertov, they invariably mention the Kinok association he founded. The word is made up of two roots — "cinema" and "eye".: That's what the young filmmakers called themselves, who shared the idea of a new approach to shooting. Vertov urged not to direct, but to "take life by surprise," and his comrades — cameramen Mikhail Kaufman and Ivan Belyakov, editor Elizaveta Svilova, directors Ilya Kopalin and Boris Zeitlin — brought this concept to life, helping their leader, and then working on their own projects.

The most interesting thing is that they achieved much more success in the official Soviet film hierarchy than Vertov, who was practically expelled from the profession from the 1930s until the last days. For example, Kopalin won the first documentary Oscar (for "The Defeat of German Troops near Moscow"), six Stalin prizes and the title of People's Artist of the USSR. But today, his name is hardly immediately remembered, not by the average movie fan, but even by those interested in that era. As well as the names of his comrades. Kirill Goryachka's book closes this gap and tells about films not only through the prism of Vertov's achievements, but also as an independent vivid phenomenon of the early Soviet cultural process — an amazing union of enthusiasts, in which the equality of all participants was declared, but in fact everything was grouped around the leader-dictator Vertov.

The researcher leaves the films of Dziga himself "behind the scenes", focusing on the relationships within the association and the process of collaboration. And this is rather a plus: a reader who has picked up such a book is probably familiar with the main works of Vertov. But what the narrative lacks is that avant-garde, structural originality, and bold editing that were at the heart of the art of cinema. In following the bare fact, the author is more consistent and honest than his hero, who actually transformed reality in the strongest way, and not only documented it.

Matyushin's wives

Alexander Laskin

Just in time for the opening of the large exhibition of Mikhail Matyushin and Elena Guro at the Zotov Center (Izvestia href="https://iz.ru/1842444/andrei-tumanov/iskusstvo-v-lubvi-v-moskve-vystavka-legendy-russkogo-avangarda-matusina " target="_blank">we talked about her) a documentary novel by St. Petersburg writer Alexander Laskin "Matyushin's Wives" has appeared on sale. It's probably a coincidence. Although it is an indicator of a surge in interest in a figure that was known only to a narrow circle of specialists a decade ago. Probably, after some time, the name of the composer and artist of the first third of the 20th century will enter the mass cult altogether, as happened with Malevich, Mayakovsky, Khlebnikov. The general public will be interested not only in his wives, but also in other details of Matyushin's stormy biography, films, memoirs of descendants, and so on will appear. In the meantime, the personal life of an avant—garde artist is an untapped field for researchers and writers. And Alexander Laskin's book only partially cultivates it, because, by and large, the main character here is not at all the one whose last name is in the title, and not even Guro, the most famous of his three companions.

It is much more interesting for the author to create an image of Matyushin's last wife, Olga Gromozova. She survived her great husband for 40 years, including the blockade, the thaw, and even the era of stagnation. Already in old age, having been blinded by a bomb explosion during the war, Gromozova became a writer. But it is purely "socialist realistic" and, in the opinion of Laskin and other experts, very mediocre. This is the paradox of the new book: we are used to the fact that the main character of the narrative turns out to be a bright figure with charm (even if negative), charisma, which we look for in literary characters. Laskin destroys this canon. He sympathetically shows the tragedy of an unremarkable man who has received much more in life than one could have hoped for, but much less than is necessary for happiness.

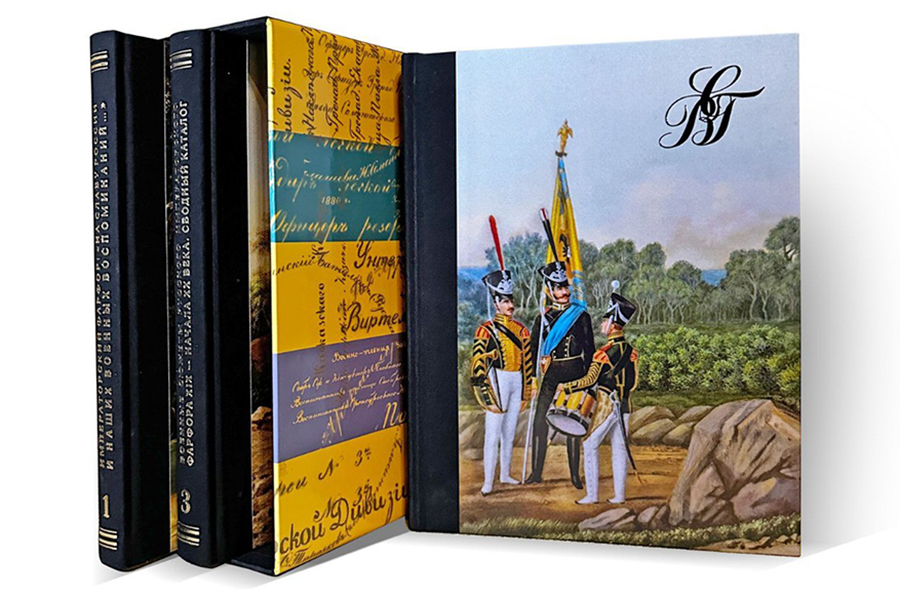

Imperial porcelain: "For the glory of Russia and our military memories..."

At first glance, the three-volume edition devoted to Russian porcelain of the 19th century seems to be a highly specialized thing aimed at collectors and museum workers, but the more you read into the descriptions of various products made of this fragile material, the nuances of the embodiment of certain plots and the circumstances of the appearance of a series of plates, the more you realize that such a local plot reflects the history of the whole country. — especially her battle line.

Actually, the fashion to depict various military scenes on porcelain appeared, as noted in the study, under Alexander I, when the whole of Europe was engulfed in conflicts, but continued after. Moreover, the Russian emperors paid close attention to her. Nicholas I personally examined the sketches before giving the go-ahead for their reproduction, and sent them for revision if he noticed the smallest inaccuracies (for example, in the image of military uniforms and insignia). Well, Alexander II, while still a tsarevich, supervised the production on behalf of his father and was often very actively and creatively involved in the process.

In a sense, the creation of porcelain with battle scenes was a kind of interpretation of recent historical events, a translation of the official view of them. And you can only learn from the masters of the past to do it so gracefully and artistically. Well, the release of this illustrated catalog nowadays also seems to be a symbolic reminder: "after all, there were fighting battles, yes, they say, some more!".

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»