To new heights: Strugatsky's cult story was reborn at the MTYuZ

MTYUZ, which last year made "Dog Heart" the main performance of the Moscow theater, presents another premiere. "Snail on the Slope" - a sophisticated mechanism, where the already difficult composition of Strugatsky acquires such versatility that you will have to watch more than once. Which, by the way, is much easier to do than with last year's hit: for "Dog's Heart" tickets go up to 14 thousand, for "Snail" the most expensive ones cost 3.5 thousand, although what the first spectators have seen is done so ingeniously and spectacularly that very soon there will be no tickets left and for nothing. So far, it's one of the season's top premieres, even with all its controversial moments that Izvestia has seen.

What Strugatsky's "Snail on the Slope" is about

The story "Snail on the slope" is less famous than "Monday begins on Saturday", "Picnic on the sidelines" or "It is difficult to be a god", but it has a very special status. The Strugatskys repeatedly said that this was their favorite work, and the charm of the story was given by the fact that it began to be printed in magazines in the mid-60s, then subjected to the harshest criticism and actually banned. The book was published in full only in 1988. Therefore, it had no choice but to become a samizdatovskogo hit, the more preconditions for this were: the story was read by contemporaries as a caustic social satire, and aesthetes appreciated it for its philosophical depth, differing, however, in interpretation.

It is worth recalling in a few words the plot of the story. It consists of two roughly equal parallel lines, both connected with the Forest, a mysterious space with unknown properties. One is the story of Silent Candide, who lives in the Forest among its inhabitants, half-witted natives. They are always talking the same repetitive nonsense, and Molchun knows for sure that he is not from here, that he is a scientist who had an accident, partially lost his memory, and now he has to go to the city. The day after tomorrow he will definitely go there.

The second story is about another "gotcha". His name is Peretz, he is a philologist and he really wants to study the Forest, but the way there is through the Directorate, which rises on a cliff above the Forest. Peretz can look at the Forest from above, but he cannot get there, because the bureaucratic absurdity of the Directorate does not allow Peretz to leave there, or at least to understand what all these employees need from him.

In the story, the lines are written out through alternating chapters and never cross. And for more than half a century readers argue what is meant by the Forest and what Strugatsky wanted to say in general, and the interpretation of Strugatsky himself (that the Forest is the future), it seems, does not suit anyone, because it confuses even more. But the line "Candide" has always been seen as a harsh parody of rustic prose, and "Peretz" as an honest description of the Soviet establishment drowning in bureaucracy.

How to watch "Snail on the Slope" at the MTYuZ

To put "Snail" on the theater stage is a thankless and, to some extent, impossible. Too voluminous, too rich material, almost four hours of performance is still not enough to place there all the brightest moments of the story - and at the same time leave space for search, because deciphering Strugatsky's prose is much more exciting than actually reading it. Besides, in "The Snail" there are a lot of unimaginable things, "given" things, which are presented in the text deliberately vague, disconnected, so that the reader does not feel confident and constantly wanders inside his own lucid imagination. How and why make it visual, literal?

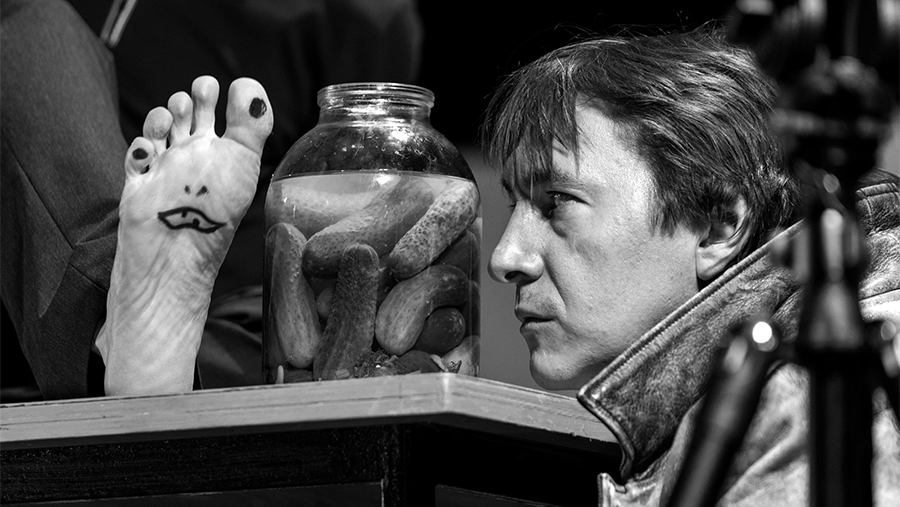

Director Peter Shereshevsky, of course, took a risk by taking on this material, but several techniques helped him a lot in his work. The first and most important addition to the text of the story is that Shereshevsky made the main characters Strugatsky themselves, not calling them by name, but achieving a certain portrait resemblance. In the playbill they appear as Composer "A" and Composer "B", and whatever line develops on stage, the Strugatskys are not just around, but become part of the action. For example, they can turn into bandits, fellow villagers or quite strange creatures. Talking to the hero through a jar of liquid that causes facial features to distort - that's the effect that is described in the story. But, besides this, of course, they also read the author's text, without which nothing at all would be clear to those unfamiliar with the story.

Another technique is the existence on stage of a microcosm connected with the macrocosm (the performance itself). For example, Peretz enters the library, and all the shelves in it are tiny miniatures on the writers' desk. But how can the viewer see this microcosm? Here Shereshevsky resorts to video cameras and two large screens hanging above the stage. There, different levels of action in every respect are united, a kind of common optics is created, linking and enabling the viewer to see everything from the angle and in the magnitude that the author needs at the moment. In other words, close-ups and details, elements of film language, supplement the director's diverse "vocabulary".

It cannot be said that this technique always works perfectly. The viewer quickly discovers that the whole "truth" of the action is most often on the poly-screen, and begins to look less and less at the stage. Because there are, in fact, several workshops working there to edit in real time "the movie", a new Strugatsky adaptation - the first for "Snail", by the way. A substantial part of the action on stage can only be seen on the screen, and this, except for the "microcosm" or chess games, applies, for example, to the moments when the hero lies in the bathtub. The actor is not visible from the hall, but the camera standing not far away looks at him.

The play somewhat lacks a "general plan", which would make the viewer break away from the screens, and this may be its weakness. Although, perhaps that was the director's aim - to show the relationship between the writer's laboratory and the sources of creativity and the result embodied in the displays. But then perhaps it would have been necessary, following the example of some Peter Greenaway, to supplement the plot with reviews, historical references, fragments of Strugatsky's diaries and other information. But the play "A Snail on the Slope" is not historical, it is not an attempt to understand how the story was created or, even more so, why it was banned. On the contrary, it is a spectator's work, addressed to today and with a minimum of 60's trappings. Even in terms of aesthetics, it's not at all about the USSR: "Pepper" is presented in the vein of Kafka's novels, and the Forest differs minimally from the Castle, while Shereshevsky staged "The Castle" and is well versed in that toolkit. The line "Candide" is more complex in aesthetics and unobvious in references, but unintentionally echoes Alexei Ivanov's recent masterpiece "Vegetation", perhaps giving away its literary roots.

And here in "Candide" is perhaps the play's main problem. "Pepper," like any Kafkaesque form, is eternal; everything is clear there about society, about the apparatus, about power, about man. Clear, but in this case, too, there is nothing new in relation to Kafka. But with "Candide" it does not "stick" to the end, and although Shereshevsky did his best to turn the two lines into a whole statement, the resistance to the esotericism of "Snail on the Slope" is too strong. However, it is possible that it will be overcome if the play, sophisticated, witty and ironic, lives on, and it must live on, because "Snail" clearly needs to be re-read and to look for answers in it, because there are definitely answers there. And since this is the only play based on the story in Moscow, its uniqueness will always work in its favor.

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»