- Статьи

- Culture

- Vampires of capitalism: how scientific and technological progress generated literary monsters

Vampires of capitalism: how scientific and technological progress generated literary monsters

The Great French Revolution of 1789 dealt a tremendous blow to religious authority and brought about sweeping changes in the European political, social, and cultural climate. The birth of the most significant monsters discussed in the book falls precisely in the twenty years immediately following the French Revolution. Among the reasons for the emergence and rapid popularity of Mephistopheles, Frankenstein, Dracula, and other monsters, Vdovin identifies both the secularization of culture and the high speed of scientific and technological progress, as well as the development of the public sphere and increased migration of the population. Critic Lidia Maslova presents the book of the week, specially for Izvestia.

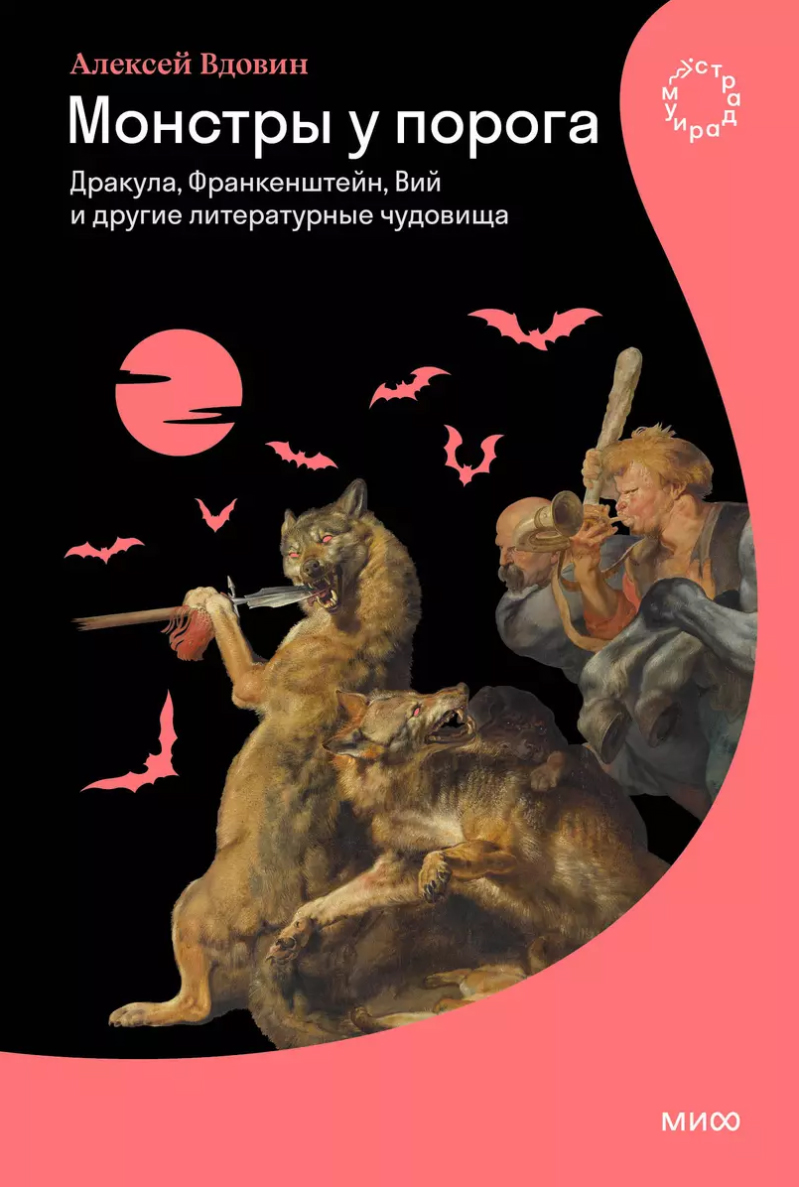

Alexei Vdovin

"Monsters at the Threshold. Dracula, Frankenstein, Viy and other literary monsters"

Moscow : MIF, 2024. - 208 с.

As a kind of pictorial epigraph to his bestiary Vdovin offers to look at Francisco Goya's etching of 1797 "The sleep of reason gives birth to monsters" and quotes the artist's own explanation: "When reason sleeps, fantasy in dreams gives birth to monsters, but in combination with reason, fantasy becomes the mother of art and all its marvelous creations". However, later the author of the book emphasizes not so much artistic as sociological meaning of marvelous, though often creepy, creations of writer's imagination: "The monster always informs us not so much about the state of the writer's psyche and imagination, but about the state of society, of which he was a part". Monsters, according to Vdovin, mark the boundaries of the permissible and the possible, which should not be crossed, and also embody those behavioral practices "that are perceived in a given culture as dangerous for it, representing an undesirable threat."

Thus, the hero of John Polidori's story "The Vampire", Lord Ruthven, pulling women into the abyss of debauchery, embodies the danger of "violation of the traditional patriarchal order, consecrated for centuries," and Count Dracula from the novel by Bram Stoker - the threat of destruction of traditional British values. The original and never seen in reality surname of the first victim of the vampire - Lucy Westenra (formed from the word west) clearly indicates, in the opinion of the researcher, the socio-political subtext of Dracula's intrigues: "Lucy becomes the first victim of the vampire because she is a carrier of western progressive democratic values. You might ask, 'Why? She's not a member of the Democratic Party and she's not fighting for workers' rights, is she? What is Lucy's 'Westernness'?" The woman leads a very easy, bohemian lifestyle. She has three suitors and cannot choose between them. In Stoker's conception, she has no firm patriarchal principles. She is a symbol of sexual freedom and looseness dangerous from the point of view of conservative Victorian ideology". And Mephistopheles, too, does not just fulfill the bizarre desires of Faust in Goethe's drama of the same name - he "is the alter ego, the inner side of humanity as a whole. This mysterious but constant force that moves a man and in his person the whole of humanity forward. That is why it does both evil and good".

In addition to not too original vampires of European style, appearing in A. K. Tolstoy's short stories "The Family of the Ghoul" and "The Ghoul", in the text by an unknown author "Ghoul on Furstatskaya Street", in Fyodor Sologub's story "The Red-Headed Guest" and others, Vdovin uses the domestic material from N. V. Gogol's story "Viy". Here, too, he finds parallels with foreign examples of the monster genre, particularly with regard to the ambivalence of the perception of various "undead" that are as frightening as they are attractive to people: "The potential connection with a vampire irresistibly attracts female representatives of the female sex in all works, and Homa Brutus in Gogol's story "Viy" is mesmerized by the striking beauty and attractiveness of the pannochka, who only at first appeared before him in the guise of a nasty old witch."

One can argue about the somewhat strained analogy between the attraction of heroines of Western literature (and cinema) to a vampire who appears to them in the guise of a gentleman who is attractive in his mystery and absolutely alive in appearance, and Khoma Brutus's attitude to the dead pannochka, about whom he initially knows that she is a cursed witch who almost killed him and is determined to see it through to the end. If you read carefully Gogol's descriptions of the eerily beautiful dead woman and Khoma's strange anxious feelings, it is difficult to see a touch of romantic charm in them: the hero sees in the features of the pannochka "something terribly piercing" and feels "that his soul began to whimper painfully, as if suddenly in the midst of the whirlwind of merriment and the swirling crowd someone sang a song about the oppressed people". Gogol subtly hints at the social aspect of Khoma's relationship with the witch: the "potential connection" with Pannochka is unimaginable for the hero, not only because the beauty is hopelessly dead, but to an even greater extent because she is class alien to him, and from her class the hero distances himself quite sharply in advance in a conversation with her father: "It is a well-known fact that the pans sometimes want something that even the most naigrammatic person will not understand; and the proverb says: "Ride, enemy, as the pans say!".

If one were to use "Viy" within the framework of the sociological approach that Vdovin declares, it would make sense to speculate that literary monsters, both Russian and Western, are bloodsuckers and murderers in the socio-economic sense of the word (the pannochka who saddled Khoma and her overbearing father behave as typical exploiters of the oppressed people in the person of the unfortunate philosopher). In the last chapter of the book, "Dracula, who is always with you", the author of the book generally turns to this idea, recalling the "extravagant", from his point of view, concept of the Italian sociologist Franco Moretti, who, in line with Marxist ideology, saw in Dracula "a symbol of the power of capital".

This idea is amusingly illustrated by the depiction of a character in Dickens' A Christmas Carol in Prose, Ebenezer Scrooge, who is also found to have much in common with Dracula: "Dickens' genius invented Scrooge, and Stoker's imagination invented Dracula. Both epitomize the power of capital. You say, "Where is capital in the novel?" That's a question for Moretti, but I've written both about the accumulated coins and the fact that Dracula buys and bribes everyone. Dracula has two weapons: bites and money." Just as Mephistopheles symbolizes humanity's craving to break boundaries and prohibitions for the sake of creating something new, so Dracula, according to Vdovin, represents "a crooked reflection of the hidden and explicit desires of most people: to satisfy their sexual needs, to have power and wealth."

Переведено сервисом «Яндекс Переводчик»